Grown Up

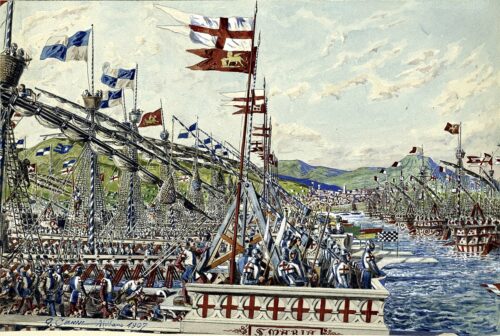

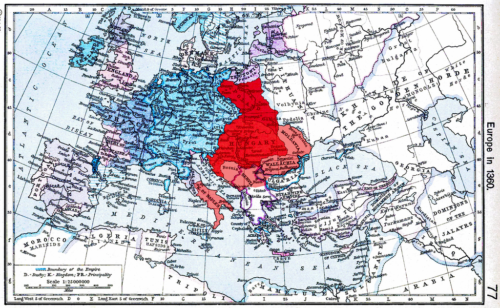

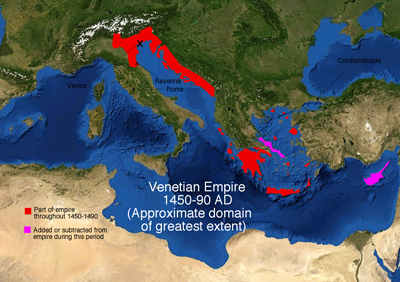

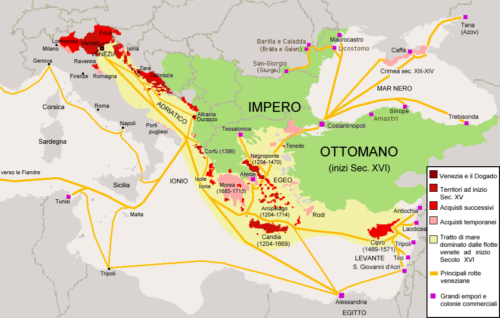

Venice gained exclusive, in essence ruling rights, to a large part, about three-eighths of the Byzantine Empire, which would be from then on known as Imperium Romaniae, the Empire of Romania or Latin Empire of Constantinople. The Venetian Doge was the first choice for the imperial crown but chose to decline the offer due to his advanced age (90 years old). He would die a year later (1205) and would be buried in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

The new emperor, Baldwin IX of Flanders , later his younger brother Henry of Flanders were assisted by a council in which the Venetian Chief Magistrate was the most influential member, practically a vicegerent independent of the emperor. The islands of the Ionian Sea, of the Saronic Gulf and the Cyclades passed under the direct control of the Venetian Stato da Màr (State of the Sea). Ten years later and after a prelude war of the full scale warfare that would follow, the Venetians take the island of Crete from the Genoese (1218) who had held it since the fall of the Byzantine capital.

The Greek islands opened up new trade routes to Anatolia & the Eastern Mediterranean which were now controlled by Venice while valuable raw materials like the famous marble from Naxos and the agricultural products mostly coming from Crete filled up the markets of the city. Trade routes became longer, transactions increased exponentially. With the increase of trade, new wealth was generated, creating a new cast of rich citizens in an unprecedented pace. Impressive new palaces like Fondaco dei Tedeschi (The fondaco– from the Arab word fonduk– then served as a multifunctional home, warehouse, and market), Fondaco dei Turchi and Ca’ Farsetti were built to house the city’s increasingly influential nobility.

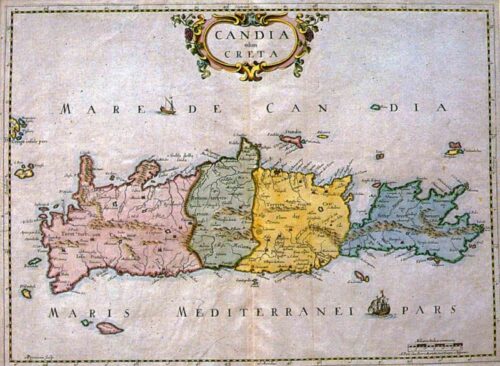

Thousands of Venetians left their cramped, damp houses to become landowners and nobles in the sun-bathed, conquered lands, without however this always being easy, as in the case of Crete for example, which would account for more than one uprisings for every single decade of Venetian occupation until the early 14th century.

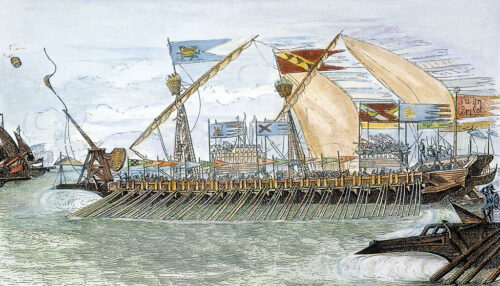

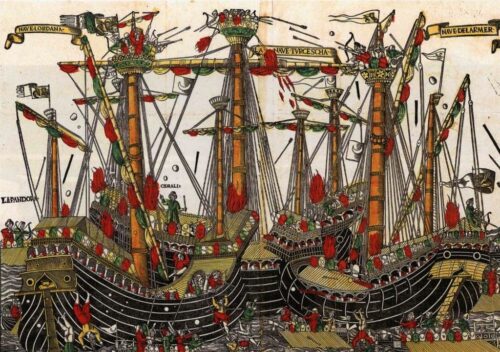

As in the case of Crete the Venetians would mainly compete with their fellow countrymen, the Genoese. In 1256 the merchant colonies of the two engaged in open warfare over a piece of land in Acre, the capital of what remained of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. In the fierce war that broke out the Venetians had with them the Pisani, the Provencals, the Knights Templar and some of the local nobility while the Genoese had the support of the Catalans, the Anconitani and the Knights Hospitaller. Nearly 20,000 men in total lost their lives in the War of Saint Sabas which ended in 1270 with a truce mediated by Louis IX of France, who wished to embark on a crusade and needed the two rival fleets for this undertaking.

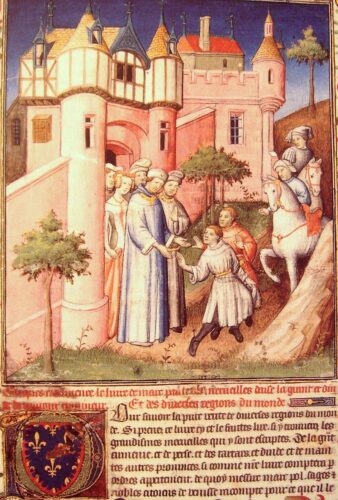

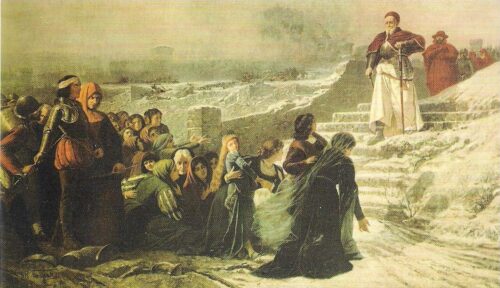

Nine years earlier Michael VIII Palaiologos, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, had reconquered Constantinople for the Greeks, had destroyed its Venetian quarter and had re-established the Eastern Roman Empire. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded, while many of those who managed to escape Constantinople had perished onboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to the rest of the Venetian colonies or Venice. One of the Venetians who foresaw the new tectonic shift on time was Niccolò Polo (Marco Polo‘s father) a merchant who had resided in Constantinople for many years and had made his name and wealth through trade with the Near East. A year before the new fall of the city to the Greeks this time, he had liquidated his assets into jewels and had moved away.

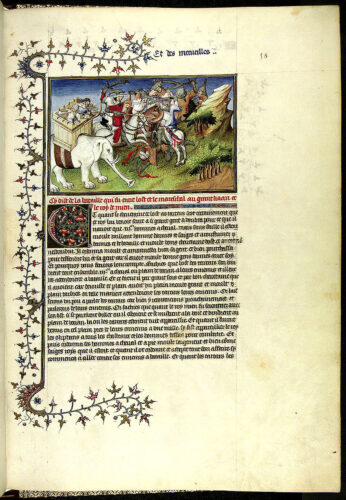

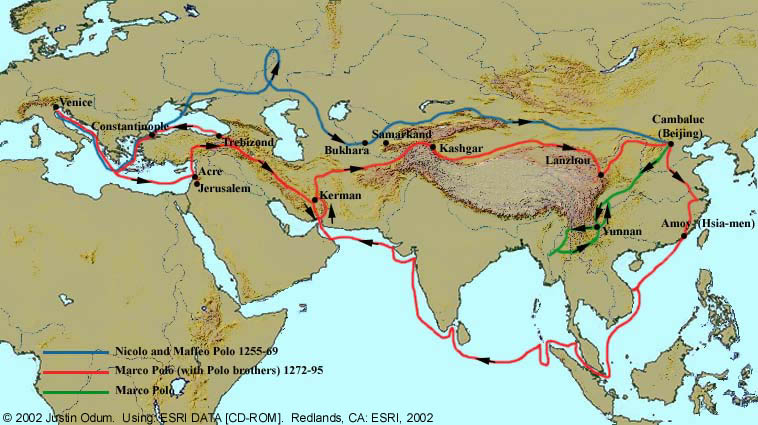

In 1269, Niccolò met his son Marco in Venice, for the first time in both of their lives. Two years later the seventeen year old Marco, his father and uncle set off for Asia. Their series of adventures would be thoroughly documented by Marco who returned to Venice 24 years later (1295) with many riches and exotic treasures, after a journey of almost 24,000 km (15,000 miles) that was meant to inspire every aspiring explorer and bold adventurer in the future.

Marco Polo’s adventures were far from over. The war with Genoa had officially re-commenced (in essence it had never stopped) and Marco Polo fell into it as soon as his galley was armed and ready. He was captured however by the Genoese in 1296 off the Anatolian coast and was kept as a hostage for several months. He would dictate his adventures to the writer and fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa. Their co-written “Book of the Marvels of the World” about the travels of Marco Polo became one of the first and most famous best sellers in the known world.

The end of the 13th & beginning of the 14th century found Venice in a very precarious state. The fall of Acre, the last Crusader stronghold in the Holy Land, to the Mamluks of Egypt in 1291, inflicted the first serious blow to Serenissima’s future prospects. The victories of the Genoese who had grown stronger, culminated with the devastating for the Venetians naval Battle of Curzola in September of 1298 when the Venetian fleet was almost completely annihilated and about 7.000 Venetian soldiers lost their lives.

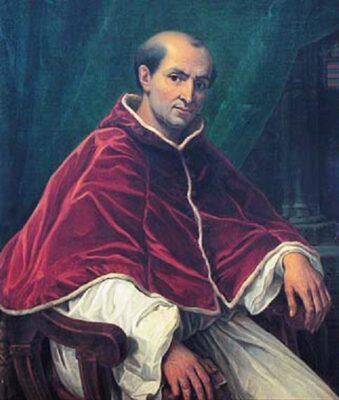

Despite the heavy losses Venice managed to build and equip a brand new fleet of galleys in a very short period of time, a remarkable feat on itself that would help Serenissima secure a reasonable truce. Although the power and colonies of the Republic were to a great extent preserved, the self-confidence of the Venetians had been significantly bruised. The popular discontent quickly morphed into a dispute about Doge Pietro Gradenigo‘s (r. from 1289 to 1311) aptitude for the job. The doge had already caused a great discord with a law that restricted the eligibility for the Great Council to only a few families (1297). The straw that broke the camel’s back became his conflict with the papacy over the control of Ferrara, which in 1308 evolved into an open warfare. Pope Clement V used all the weapons at his disposal. In March 1309 the Republic was excommunicated and all Catholics were barred from trading with Venice. He then preached for a crusade against the Venetian Republic (May 1309), declaring that all Venetians captured by other Catholics could be sold into slavery without the worries of a sin, similarly to the practice followed for non-Christians. In June 1310 the members of some of the oldest aristocratic families in Venice organised a conspiracy to overthrow the doge and the members of the Great Council. The rebels were crushed near Piazza San Marco by the forces faithful to the Doge. During their retreat the wooden Rialto Bridge was burnt down. The leaders of the rebellion were exiled and their houses were razed to the ground. Another response to the revolt, was the creation of the Council of Ten, a governing body, of one-year term and emergency powers, with a task to preserve the government in cases of rebellion or corruption, that was established in July 1310. The members of the council were to be confined in the Palazzo Ducale during their whole tenure and would not be able to hold their post for two successive terms in order to prevent corruption or bribery.

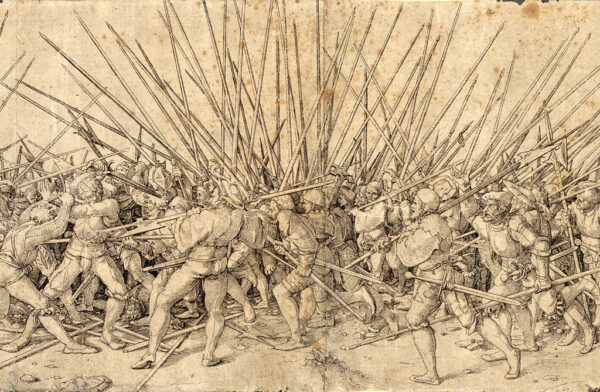

People from the colonies in southern Greece and Croatia, from other Italian cities and France, Jewish people who found an ideal city to do business (lending money with interest was only a sin to Christians at the time), merchants and builders from the Holy Roman Empire, all flocked in the booming city which by 1300 had a soaring population of around 100.000. In the first half of the 14th century Venice waged new attacks against Byzantine outposts, had its first serious skirmishes with the advancing Turks in the east and was implicated in a full scale war against their ambitious neighbours from Verona who had seized the control of Vicenza, Padova and Treviso. Venice formed an alliance with Florence, Siena, Bologna and Perugia enhancing its own army of about 40.000 citizen soldiers who were conscripted for the war contrary to to the usual practice of the time which was the hiring of mercenary soldiers. A peace agreement that secured the interests of Venice was sealed in 1339, in St. Mark’s Basilica.

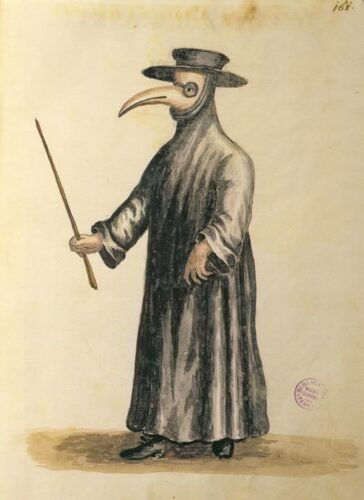

In the beginning of 1348 a double blow would bring the city to its knees. A great earthquake that had its epicenter in the neighboring region of Friuli would cause hundreds of casualties and destroyed houses. It coincided with an outbreak of the plague that wiped out about a third of the overall population. The two tragic events sparked apocalyptic fears to many god-fearing Venetians. Despite the calamity Venice had to recover and protect its interests abroad. In 1345 after numerous insurrections the Dalmatian port-city of Zadar which had been under Venetian rule since the early 1200’s, formed an alliance with King Louis I of Croatia-Hungary. As if that wasn’t enough Genoa joined in, with its fleet devastating Venetian territories and threatening the city itself , which was saved only after winning a decisive naval battle off the coast of Sardinia together with the help of the Catalan fleet in 1353.

The terms of another fragile peace between the naval superpowers of the time would be imposed by the superior at that point in time Genoese Republic. The heavy economic burden that was laid at the shoulders of the Venetian treasury as compensation by the Genoese caused a huge public discomfort that was funneled towards the ruling aristocracy. The newly appointed Doge Marino Faliero (September of 1354) tried to take advantage of the momentum, set aside the oligarchic government and establish a dynastic rule. The reflexes of the aristocratic elite proved to be sharp enough and after just few months in power the new doge was found guilty of treason. He was beheaded and his body was mutilated. His portrait that had been displayed at the Hall of the Great Council since his election was removed and the space was painted over with a black shroud with the inscription Hic est locus Marini Faletro decapitati pro criminibus (“This is the space reserved for Marino Faliero, beheaded for his crimes”). The rest of the conspirators were hanged from the balconies of the recently revamped in Gothic style Palazzo Ducale for everyone to see. One of them was the architect himself.

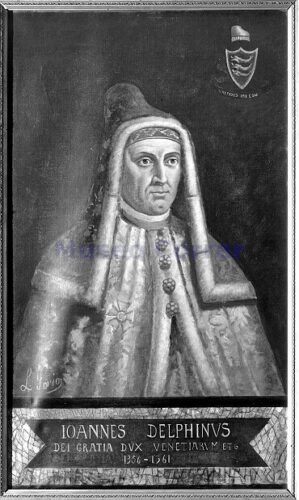

In 1356 Giovanni Delfino, a general of proven value and member of one of the most prominent noble families in Venice would take over the helm and the momentous task of reversing the descending spiral of the Republic but things would become worse before they got better. In 1358 the army of King Louis I crushed the Venetians on land and seized the control of the the whole Dalmatian coast. In the same year Padova managed to halt the city’s trade with Egypt, triggering a serious economic crisis. The new doge would die of plague three years later, closing his ill-fated spell with his burial in the new resting place for doges, the Basilica di San Giovanni e Paolo.

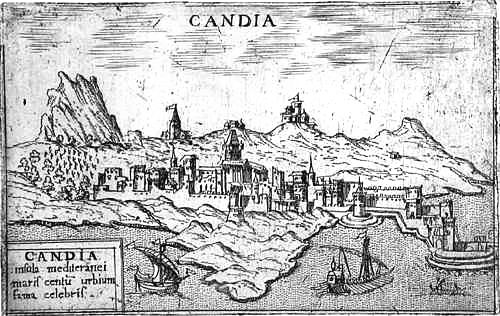

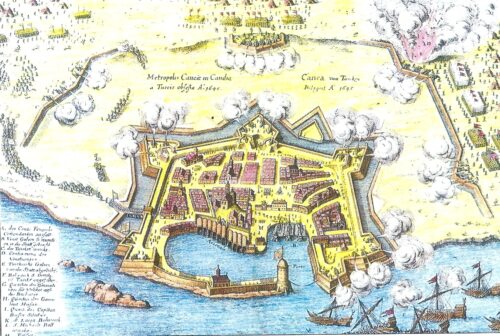

The constant warfare and the continuous need for a combat-ready fleet increased the demands laid upon the colonies by the Venetian state. A new tax imposed on August of 1363 on Candia (Heraklio), the capital of the colony of Crete, despite the fact that it was set out due to the need for maintenance of the city’s port, roused the locals and the Venetian feudators who had been living in Crete for two or three generations by then. Both groups viewed the tax as a burden that fell on the shoulders of the ones who would benefit less from the improvement. The merchants of Venice where the ones who had to pay.

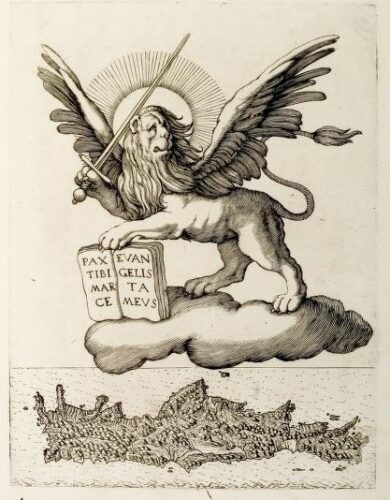

The Revolt of St. Titus spread like fire the whole island, with the Greeks fighting side by side with the Venetian insurgents, taking over the control of the main cities on the island, proclaiming their independence and establishing the Commune of Crete with the figure of St. Titus (instead of that of St Mark), serving as the new state’s emblem.

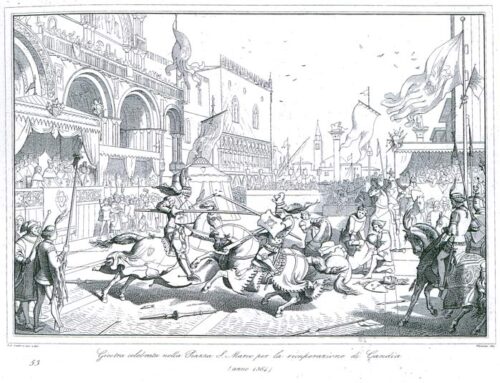

Too much was at stake for Serenissima which saw Crete as the crown-jewel of its Empire. A request for a boycott against Crete was sent out even to long-time enemies like the Doge of Genoa and Louis I of Hungary while an appeal for military aid would succeed in the formation of a multinational mercenary army, led by a Veronese general. The army would reconquer the main cities in just a few days and scatter the rebels who fled to the Cretan mountains in May of 1364.

The Venetians had just managed to fully subdue Crete when the third and final round of the bras de fer with Genoa started to unfurl. In the War of Chioggia that started in 1377, what sparked the collision was the control of the small island of Tenedos that could hinder the access to the Black Sea, through the strait of the Dardanelles.

Venice formed an alliance with the Kingdom of Cyprus and Milan while Genoa sided with Hungary, Austria & Padova. Very close to being a complete disaster, the war was saved when the invading Genoese fleet was trapped in the harbor of Chioggia in December of 1379. The Peace of Turin in 1381 closed a series of disastrous wars with considerable losses of territories (islands of Chios, Lesbos, Tenedos, surrender of Treviso and recognition of Genoese supremacy in Cyprus) and an even more significant detriment in the field of economy.

Despite the severe damage in the Republic’s affairs the Venetian ingenuity found a way to make its public finances bounce back mostly after the re-establishment of the trade with Egypt. By 1400 a new wing at the Doge’s Palace, most of the work in the Basilica di San Giovanni e Paolo and the last touches in the imposing Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari were all complete. The two churches followed the new Venetian-Gothic style that prevailed in the city’s palazzos in the 15th and 16th century.

The good condition of the state’s treasury in contrast with the situation in Genoa which entered a deepening financial crisis because of the war, allowed a new round of military claims for Venice, this time in the Italian mainland. The neighboring rival cities of Padova and Verona were forced into submission by 1405. By 1410 the eastern coast of the Adriatic was under Venetian rule again. By 1420 most of the territories under the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (Udine, Friuli & others) were forced to accept the rule of Venice. The empire was growing again.

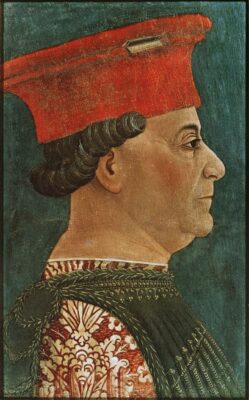

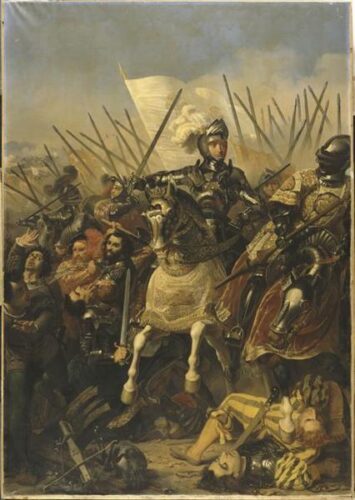

The period that followed until the year 1450 was marked by the confrontation of Venice with the ambitious Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan and the increasing influence of various distinguished Condottieri, professional mercenaries who were employed by powerful Italian city states, changed sides without hesitating and won battles based on the detailed information they had previously mustered.

The most famous case of condottiero in the service of Venice was that of Francesco Bussone da Carmagnola. Born near Turin, in a humble peasant family, he started his military career in the service of the Viscontis of Milan early on and by his 30’s he had already clawed his way up to the highest rank of the Milanese army. In a very short period of time he managed to win over several cities for the Milanese with Genoa being one of them. His rapid success & abilities scared the Milanese duke who tried to secure his own place against the rising star. Instead of trusting the condottiero with the general command of the Milanese army he appointed him governor of Genoa. Carmagnola however rejected the honorary position and offered his services to the new Venetian Doge Francesco Foscari.

The information which Bussone carried with him about the functions of the Milanese army in a time when Milan pursued the expansion of its realm outside the limits of northern Italy and the raging war of Milan with Florence left no room for doubts about who would be next in the Milanese list. That threat prompted the doge to entrust Carmagnola with the position of Captain-General of the Venetian army in 1426. Soon after, war was declared and Venice joined Florence in her fight against Milan.

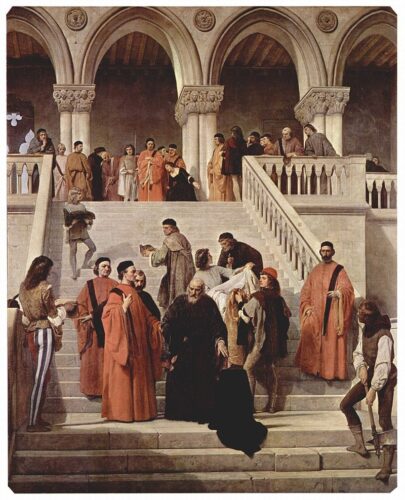

Bussone quickly took Brescia for Venice but then he started to follow a tactic very popular in the soldiers of fortune, he began to stall. The more the time the bigger the revenues for mercenaries. The bigger the expenses for Venice of course which started to catch on to his tactics and demanded a new victory in order for him to keep the command. An important victory was delivered at the Battle of Maclodio in 1427 but the stalling tactic continued right after it. By 1432 the patience of the Venetian rulers had been evaporated. Bussone was summoned to Venice by the Council of Ten with the pretext of a discussion on future operations. He was imprisoned and brought to trial for treason against the republic in March of 1432. He was condemned and beheaded in May 1432.

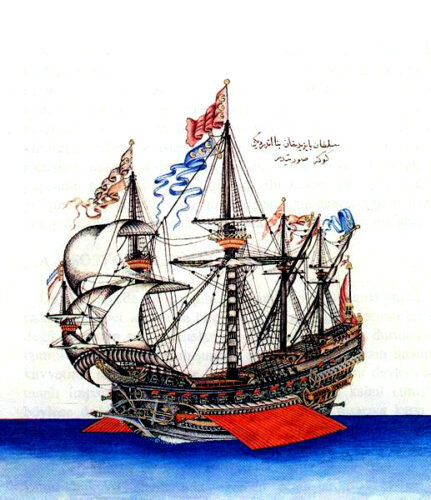

Until the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, Venice was the undisputed maritime superpower of the eastern Mediterranean. In the new reality the Venetian galleys would have to compete with the armadas of the constantly expanding Ottoman Turks who threatened to turn the lucrative naval routes of the Aegean, Black Sea and the Levante into their own private lagoon.

The first Ottoman–Venetian War started soon after the capture of Constantinople and included several Venetian and ex-Byzantine territories that were all lost to the Turks by the end of the war in 1479. The Republic managed to recoup its losses with the acquisition of the last Crusader state-island of Cyprus in 1489.

The migration of Byzantine Greeks to the west had already started after the first fall of Constantinople in 1204 as a reaction to the evident decline of their empire. After the fall of their capital to the Muslim Turks a massive wave of Greek scholars, writers, poets, printers, lecturers, musicians, astronomers, architects, academics, artists, scribes, philosophers, scientists, politicians and theologians began to settle in territories of the Republic of Venice, including Venice itself which by 1479 had a population of about 5000 Greek residents, in their majority highly educated.

The Greek scholars and their extensive knowledge of the ancient Greek and Roman texts would play a crucial role in the revival of Greek and Roman studies and the subsequent development of Renaissance humanism. Spurred by the Peace of Lodi in 1454, that became an agent of relative calm to the region of Northern Italy for the first time in centuries, the spirit of Renaissance spread in Venice and the rest of the Italian cities mainly through the novel creations of their talented artists.

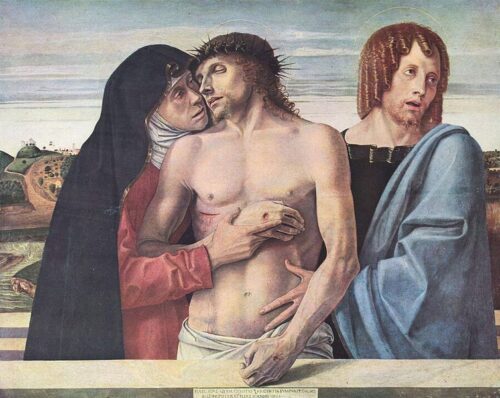

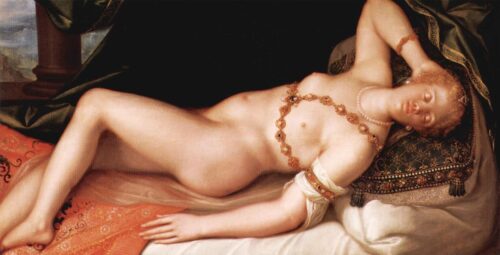

Colossal talents that would be admired by laymen and fellow artists for hundreds of years to come, worked in Venice during the second half of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th. Especially Venetian painters would change the face of their craft by creating a new distinctive school, the Venetian school, a school more sensuous and coloristic, harbinger of a more optimistic era. Jacopo Bellini (1400 – 1470) Lazzaro Bastiani (1429-1512), Gentile Bellini (1429–1507), Giovanni Bellini (1430–1516), Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506), Giorgione (1477-1510), Bernardino Licinio ( 1489 – 1565), Titian (1490 – 1576) and Tintoretto (1518– 1594) all lived and created their masterpieces in Venice in the latter half of the 15th and first half of the 16th century.

The unfavorable for the Venetians Treaty of Constantinople in 1479 ended, at least temporarily, the fifteen-year old conflict with the Turks and allowed the Republic to turn its full attention towards its terra firma (main land) and its Italian neighbors. At that time, Venice felt and acted as a superpower which basically meant that no violation of its sovereign rights could be left unanswered. In 1480, Ercole I d’Este, a man who had become Duke of Ferrara in 1471 with the support of the Republic would step into its most important and long established trade monopoly by taking control of the salt-ponds of Commachio just south of the Venetian border-line.

In the War of Ferrara that started in 1482 Venice had the support of the papal troops and contingents from the Republic of Genoa and the Marquisate of Montferrat that stood against those of Ferrara, Naples, Milan, Mantova and Bologna. The Venetian troops quickly overrun Ferrara’s forces and in November of 1482 laid siege to the city of Ferrara itself. However the Pope would change sides and Venice had to suffice with minor territorial gains with the Treaty of Bagnolo in 1484, marking the historical zenith of the Venetian Empire. Never again would Venice control so much land and possess so much power as in the late 15th century.

Sensualism was not just something that permeated Venetian paintings of that era. 15th century Venice was a very erotic city. In fact prostitution was a practice that was encouraged from the Venetian state as a way to combat homosexuality that especially after the plague of the 14th century and the plummeting of the general population became a matter of governmental concern. About 11.000 licensed city prostitutes were working towards the end of the 15th century in a population of about 150.000 people, with many more unofficial streetwalkers who couldn’t be counted because they weren’t in a brothel, and women who worked at the job part time when money was tight. The analogy was by far the biggest in Europe.

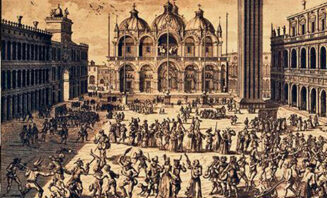

The fame of the Venetian prostitutes, the puttana (the ones working out in the streets or in the taverns), meretrice pubblica (the ones working in the licensed brothels) or cortigiana (sophisticated, beautiful and highly paid) and Venetian brothels spread across Europe with the city’s bustling port acting as the best marketeer. Εasy access to carnal pleasures wasn’t the only thing igniting the world’s imagination about the alluring city that was built on water. The first record of the Venetian Carnival dates back to a document of 1094 by Doge Vitale Falierο , which speaks of public entertainment and mentions the word Carnival for the first time. By 1296 the Senate had declared the day before Lent a public holiday while by 1436 the so-called mascareri (mask makers) had been officially recognized as a profession with a statute, according to the State Archives.

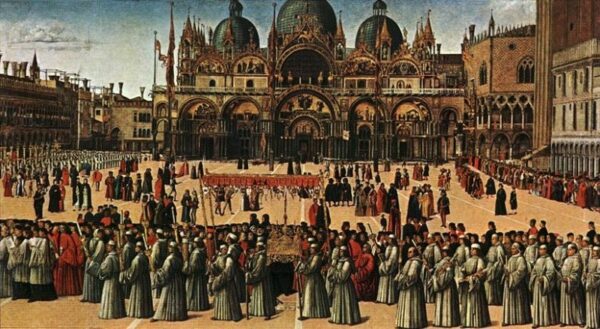

Supported by the Venetian oligarchy who saw the carnival as a harmless and useful de-pressurizing valve of the bridled by religious conservatism masses, the carnival was quickly braced by the people of Venice. By the year 1500 the period of the festivities had been stretched to 40 days in total. Excessive drinking, partying, fun and festivities, all covered in a cloak of anonymity guaranteed by the masks and costumes, managed to soften almost all social divisions. Bull races and ceremonial sacrifices, wrestling and gymnastic displays, parades leading to Piazza San Marco, official ceremonies led by the doge, competitions between the siestres (districts) of the city, jugglers, acrobats, musicians, dancers, animal shows and various other performances, entertained a varied audience of all ages and social classes. Vendors sold all kinds of merchandise, from seasonal fruits to rich fabrics, from spices to food from distant countries, exotic lands of the East, combined with crowds wearing or buying elaborate masks and fancy costumes created a mesmerising atmosphere that celebrated life and pushed all serious affairs of the state to the sidelines. By the mid 16th century the Venetian Carnival was famous enough to attract visitors from all the corners of the European continent.

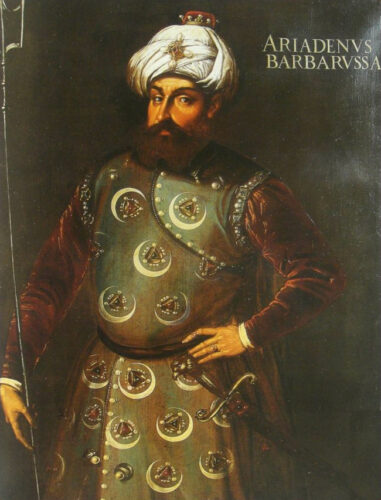

Of course not everything was rosy for the Venetian Republic even at that time of heyday. In 1499 a new, more vicious round of warfare with the Ottoman Turks would recommence over the control of the Aegean and Ionian Seas. By 1503 the Venetian galleys had been defeated in several naval battles by the war ships of the Turkish admiral Kemal Reis who managed to overwhelm several Venetian positions in Greece. In 1503, Turkish cavalry raids reached Venetian territory in Northern Italy, and Venice was forced to recognize the Ottoman gains, ending the war.

In the same year (1503 was the year the infamous & controversial Pope Alexander Borgia died) the plea for help by the dispossessed by the Borgias lords of the Romagna, one of the richest regions in Central Italy, in exchange for their submission to the Republic of Venice, would implicate Serenissima into the uneven war against the League of Cambrai, a huge anti-Venetian coalition under the new Pope Julius II that broke out in 1508.

The joint forces of the Papacy, France, the Holy Roman Empire and Ferdinand I of Spain, each and everyone eager to take some part of Venetian territory for their own, were too much to handle even for the mighty Venetian Empire. On May 14th 1509 the Venetian army was crashed in the Battle of Agnadello, where more than four thousand of its soldiers died and as Machiavelli puts it in his most famous work “The Prince”, it took one day for the Venetians to lose what it had taken them eight hundred years to conquer.

French and Imperial troops occupied Veneto, all land accumulated in northern Italy during the previous centuries was lost to the French, the Apulian ports in the south were ceded in order to come to terms with Spain. The papal army invaded Romagna and seized Ravenna with the help of the Duke of Ferrara. In the same time Pope Julius II issued an interdict against Venice excommunicating every citizen of the Republic. It was a complete meltdown.

Still the Venetian stamina and notorious diplomatic prowess managed to come through once more. Taking advantage of the papal concerns over the increasing French presence in Italian territory, the Republic formed a new alliance with the Pope who switched sides when in the same time, it supported the revolts of the conquered cities against the foreign invaders. The Veneto-Papal alliance became official and went on the offensive, managing to win over several cities by the beginning of 1511. Despite the remarkable rebound however, the year 1509 marked the historical end of Venetian expansionism.

The Pope continued to look for ways to oust the French from Romagna once and for all and since the League of Cambrai was in essence void, he called for a formation of a new Holy League against the French in 1511. The Venetians played a crucial role in the reconquest of Milan in 1512. When Emperor Maximilian I -who was now on the same side- refused to surrender the territories of Veneto and after the endorsement of his decision by the Pope, Venice turned to France signing a treaty in March of 1513 that stipulated the division of Northern Italy among the two allies in a bold move of Realpolitik. The move by Doge Leonardo Loredan proved to be insightful. France won the war against the Holy League and Venice was able to take back the territories it had lost after 1508. In addition the Papacy was forced to repay its debts to the Loredan family, approximately 500,000 Ducats, which was an enormous sum of money.

In another corner of the earth things wouldn’t play out as well. Until 1509 the Venetians were the ones in complete control of the extremely lucrative European spice trade by monopolizing the flow of spices from India to Europe, through their alliance and trade agreements with the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt that extended across the largest part of the Red Sea coastline. Despite its reinforcement by Ottoman vessels which had been disassembled in Alexandria by Venetian ship-builders and reassembled on the Red Sea coast, the Egyptian navy would be crippled by the Portuguese fleet in 1509 in the Battle of Diu off the coast of India. Venice would no longer have its monopoly.

Some things in Venice did not depend on the political or military struggles. Venetian glass-making fell into the category of things that by the end of the 16th century was standing on pretty solid foundations. By then the island of Murano was almost completely inhabited by skilled glass-makers who were inventing new methods and techniques that offered prestige to their guild and wealth to their city. The Venetian glass production had acquired such a fame that the status of the producers was considered equal to that of a Venetian nobleman. In its effort to keep their techniques a secret, the Republic didn’t allow them to leave the country. The exportation of professional secrets was punishable by death. In vain however since Venetian-style glassware would soon be produced in other Italian cities and several European countries that managed to take hold of the patents.

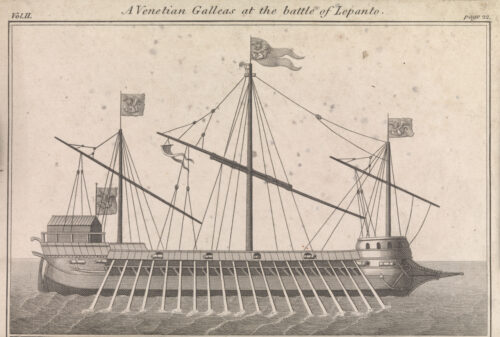

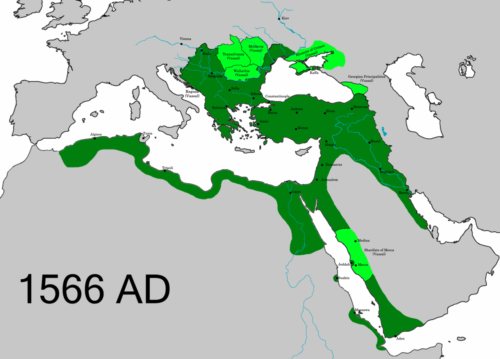

The Third Ottoman–Venetian War (1537–40) and Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–73) would weaken the Venetian position in the East even more and cost the loss of most of the Cyclades in the Aegean, the strongholds of the Peloponnese in mainland Greece and the island of Cyprus. Despite the crushing defeat of the gigantic Ottoman fleet of 300 ships in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 by the new Holy League, the vast Ottoman reserves would prove enough to re-confirm the solid Ottoman control of the Eastern Mediterranean with the sole exception of Crete that still remained under Venetian rule.

The new ocean trade that was born after the discovery of America and the new route to India, made ocean-going vessels more important than the Mediterranean galleys. The Portuguese caravels would make Portugal Europe’s primary intermediary in the trade with the East and dethrone Venice from its position as the most important center for international trade. The irony of things was that at that time the Venetian Arsenal’s ability to mass-produce galleys had reached its apogee and was incomparable to any shipbuilding enterprise in the world. With almost 16.000 workers and the capacity to produce fully equipped merchant or naval vessels at the rate of one per day, the Arsenale Nuovo was the single largest industrial complex in Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution. In 1593 the mythical figure of Galileo Galilei himself became a consultant to the Arsenal, advising military engineers and instrument makers and helping to solve shipbuilders’ problems, many of them relating to matters of ballistics.

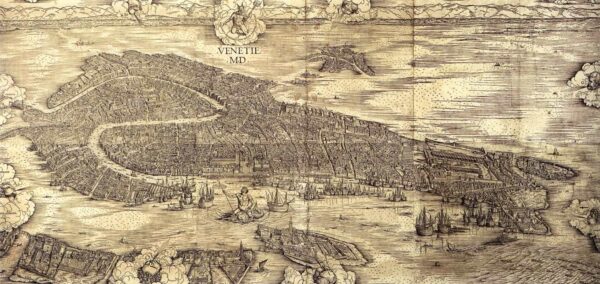

The problems of the Republic mirrored in the course of the general population which reached its peak in the mid 16th century topping at about 180.000 inhabitants (when London had a little more than 70.000 and Milan 75.000) and then dropped to a little more than 150.000 by the beginning of the 17th century, a trend that would continue in the following years.

Until the end of the 16th century the great need for financial instruments produced in a bustling trading center like Venice was covered by private banks, local bankers who kept their customers’ deposits and transferred money by simply writing the sum from one account to another. The reality was perfectly portrayed in Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice written between 1596 and 1598.

The bankruptcy of five of those bancos di scritta in 1568 created the need for the first public bank, the Banco della Piazza di Rialto which assumed the role played by the private banks before their failure. It was the second state institution of its sort to open in Europe, a few years after the establishment of the London Royal Exchange. After 1637 the first public bank in Venice which was ruined by bad loans was replaced by the Banco del Giro which was controlled by the Senate and was an essence a new institution of the Republic the first public bank in Venice was replaced by the Banco del Giro that took over the same role and became a permanent institution of the State and a progenitor of modern central banks.

By the year 1600 several architectural landmarks like the Doge’s Palace that had been destroyed by a series of consecutive fires during the 16th century, the Biblioteca Marciana, the Rialto Bridge and the Bridge of Sighs had all been completed, giving the city, the key elements of its appearance, identified and admired in every corner of the civilized world up to this day.

The weakening Venetian economy fell into a new vicious circle with the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War and the loss of the German market in 1618. In the same time the Republic had to pay a substantial amount of money that went on incessantly since the 1590’s, to fend off against the attacks of the Uskok pirates (Croats, Serbs and Bosnians who had fled their conquered by the Ottomans lands and had settled the coastal lowlands around Split). The fact that the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I had made those same pirates his vassals in his effort to use them as cushioning against the Ottomans, complicated things even more. The matter was resolved with another costly war known as the Uskok War that was fought against Austrians this time ending with peace treaty that put an end to the pirate problem in 1618.

A new war in 1628 against the Habsburgs on the occasion of the designation of the new Duke of Mantua would implicate Venice in Italian politics for the first time in more than a century. The consequences would be disastrous not so much because of the defeat of the Venetian army but mainly because of the plague it brought back to Venice in 1630. The disease ravaged the city wiping out more than 45.000 people (the number reached 94.000 if one included the victims of the wider region) in a general population of 140.000 in 16 months. Some historians believe that the tremendous loss of life, and its impact on commerce, ultimately resulted in the downfall of Venice as a major commercial and political power.

Like the calamity of a pandemic was not enough the Republic was swirling around the whirlpool of civil war since the end of 1628, between the supporters of the reigning Doge Giovanni I Cornaro a faction that was pro-papal and was backed by the Venetian oligarchs and the supporters of Renier Zen, a leader (capi) of the Council of Ten and a great criticizer of the Doge, a faction that was anti-papal and backed by the poorer nobility.

As a true harbinger of modern societies Venetian life of the early 17th century presented many of the bad habits that modern man is accustomed to. Illegal gambling had become a serious problem in the city despite the efforts of the Venetian authorities who had put a ban on games of chance popping up at an alarming rate in various corners of the city’s streets. As a result of the clamp down, many private houses were converted into illegal casinos known as Ridotti (Ridotto comes from the Italian word riddure, meaning to close off or make private). In an effort to control the situation, the city leaders would open the first government-owned casino at the Palazzo Dandolo in 1638. It would be the first legal casino in the history of the Western world.

After the loss of Cyprus in 1570, the Republic was very careful not to provoke the Ottomans who appeared to have far more military might and resources than the panting city-state of Italy. After more than sixty years of peaceful relations and uninterrupted trade transactions however, the Venetians were the first to provoke a reaction with the bombardment of Avlona, in today’s Albania, part of the Ottoman Empire at the time, where a fleet of Barbary pirates had fled seeking protection in 1638.

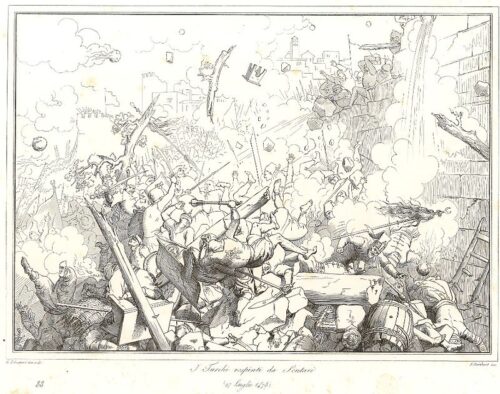

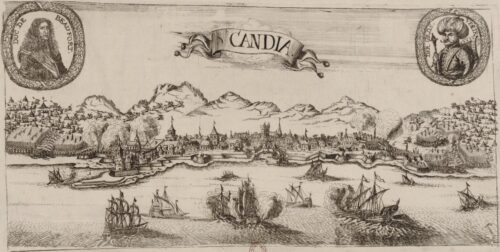

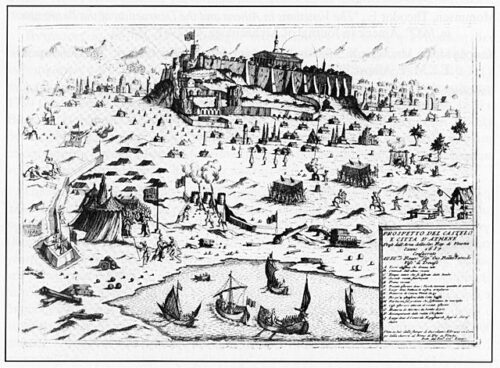

In 1644 an attack on an Ottoman convoy bound for Mecca by the Knights of Malta who slayed all the men on board (sailors and pilgrims) and then docked at a small harbor on the southern coast of Venetian Crete became the final straw for the hawkish Ottoman court. The Venetians vehemently denied their involvement in the incident but the dice had already been cast. The fertile lands and plethora of natural ports of the Greek island had for long been in the Ottoman target as the only non-ottoman territory in the eastern Mediterranean since the end of the 16th century. Fifty thousand troops and more than 400 ships sailed from Constantinople in April 1645 heading towards the last major overseas possession of Venice.

Although the first city (Canea in Venetian, today’s Chania) on the western side of the island fell relatively quickly (56 days), the capital of the island, Candia (today’s Heraklion) would manage to withstand from 1648 when the siege began, until September of 1669 when Captain-General of the Venetian forces on the island and future Doge Francesco Morosini negotiated its surrender. It would be the second longest siege in history after that of Ceuta (1694-1727) by the Moors.

The Venetians wouldn’t lay down their arms so easily. Encouraged by the defeat of the Ottoman army in the Battle of Vienna in 1683 the Venetians declared a new war against the Ottomans on April of 1684. Enhanced by men and ships from the Knights of Malta, the Papal States, the Duchy of Savoy and mercenaries from several German states, especially Saxony, they started winning back several outposts in the Ionian Sea. The maestro of the avenging expedition was none other than Morosini who had been accused of cowardice and treason upon his return to Venice, after the surrender of Crete in 1669 but was acquitted after a brief trial. In the so-called Morean War that followed, Morosini and his troops managed to win over the whole of Peloponnese in only two years. The success caused great joy in Venice, and honors were awarded on Morosini and his officers. Morosini received the victory title Peloponnesiacus, and a bronze bust of his was placed in the Great Hall, something never done before for a living citizen of the Republic.

Success increased Morosini’s appetite who decided to head north towards Athens which after so many years of Ottoman rule was nothing more than a provincial Ottoman town. The garrison of the city retreated in the famous Athenian Acropolis that had been used as a gunpowder warehouse by the Turks after 1640. On September of 1687 a shot hit the building causing the destruction of the temple’s roof and most of its walls. Despite the capitulation the Venetians would only keep Athens for a few months before retreating to the Peloponnese. Before his retreat Morosini completed the destruction of the temple by looting many of the sculptures. Although he was honored with the election as a doge upon his return in Venice in 1688 he is mostly remembered historically for his unfortunate contribution in the destruction of one of mankind’s most important monuments.

The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 confirmed the Venetian possession of the Peloponnese and the islands of Aegina, Lefkada, and Zakynthos. Still the gains were not enough to compensate for the huge loss of life and monstrous expenses of the wars with the Ottoman Empire. In the same time the new Venetian Kingdom of Morea required evenn more expenses in order for some military readiness & elementary defense to be secured.

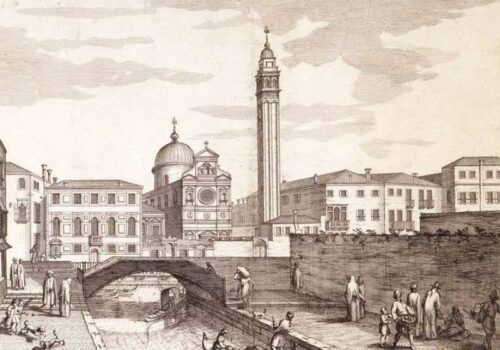

After the end of Morosini‘s dogeship the Venetians decided to elect someone less ambitious with the hope he would lead them into a more peaceful era. Silvestro Valiero was just that. With no special talents aside from his good looks and fluent speech the new doge was more interested in hosting lavish celebrations and banquets. After his death in 1700 a huge tomb was erected in Basilica di San Giovanni e Paolo for him, his wife and his father by Andrea Tirali, architect of Ponte dei Tre Archi, San Nicola da Tolentino, San Vidal and Palace Manfrin.

In the new European conflict, triggered by the death of the last Habsburg King of Spain, Charles II of Spain in 1700, Venice chose to stay neutral despite the efforts by both France and the Habsburg empire to win its support. On the Eastern front the Ottomans were not willing to let the Kingdom of Morea remind everyone of their defeat by an inferior power. Encouraged by their victory in the Russo-Ottoman War of 1710–1711 and the favorable Treaty of Adrianople in 1713, the Turks declared war on the Republic in December 1714. A huge army of 70.000 men left Constantinople for Morea which was defended by 5.000 strong, scattered among the various fortresses.

In a few months the Kingdom of Morea had been lost along with several other Venetian outposts, including the last remaining in Crete that followed next. It would be the end of Venice as an important, competitive military force. Some last naval expeditions in 1717 & 1718 were unsuccessful. The last Ottoman-Venetian War (1714-1718) sealed the Republic’s political future and the closed last chapter of its seaborne empire. The Republic would now focus in its cultural life and continental domains which extended west almost to the city of Milan and east across the most part of the Dalmatian coast.

Culture was always among the strongest suites of the Republic. One great example was its relationship with music. In 1637, after a long period of private theaters owned by the wealthiest aristocratic families and attended exclusively by nobles, the first public theater Teatro San Cassiano dedicated to opera, opened its gates in the parish of San Cassiano near the Rialto. It was the first public opera house in the world. In 1639 Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo premieres with an opera and quickly attracts famous sopranos and composers of the era. Teatro San Moisè opens its gates with Claudio Monteverdi‘s (now lost) Opera L’Arianna in 1640. It was followed by Teatro San Samuele in 1655 (used primarily for plays but more closely associated with opera and ballet in the 18th century), Teatro San Salvatore in 1661, Teatro San Giovanni Crisostomo in 1667 and Teatro San Angelo in 1677. The opera craze of the 17th century had been spurred by the wealthy patrician families like the Grimani who saw the decline in the traditional overseas trading and decided to invest in opera at a time when the art form was still put on trial for exhibitionistic display in the rest of the European countries. It had followed the birth of the very distinct Venetian polychoral style, a type of music that marked the passage from late Renaissance to the early Baroque era and was created as an adjustment to the the architectural peculiarities of the Basilica San Marco in the late 16th century. The opera was later transformed by the famous Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi who in 1613 started working in San Marco as conductor. He wrote most of his opera masterpieces in Venice where he was buried in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in 1643.

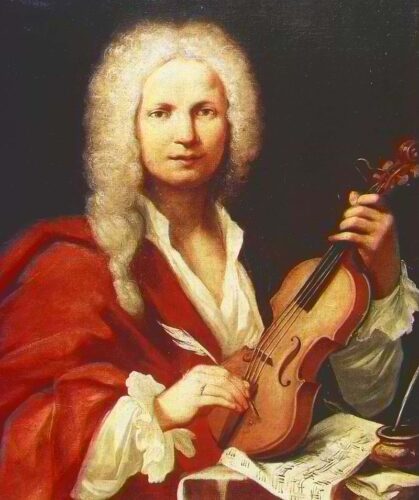

The unique cultural hive that was Venice in the 17th century and 18th century would shape the brilliance of two colossal figures in the history of art. In 1678 Antonio Vivaldi is born in Venice. His father a barber before becoming a professional violinist, taught Antonio to play his favorite instrument and then toured Veneto playing the violin with his young son. At the age of 25 Antonio Vivaldi became maestro di violino (master of violin) at an orphanage-convent-music school in Venice, called the Ospedale della Pietà (Devout Hospital of Mercy). Most of his compositions, written in the 30 years he worked there would change music forever. In 1707 Carlo Goldoni is born in Venice. His witty unconventional plays would place him in the same category as Moliere and would be played without interruption in every theater of the world to this day.