Adolescence

The son of Pietro II Orseolo, Otto Orseolo would take over the dogeship after the sudden death of his elder brother in 1006 and his father in 1008 at the young age of 16 years old. Otto Orseolo continued the pursuit of good relations with both the Holy Roman Empire & Constantinople until his excessive nepotism enraged his fellow citizens and gave the excuse to the enemies of the Orseoli in Venice to pull the strings for his deposition. In 1026 Otto was arrested, shaved (an act of humiliation according to the contemporary customs) and banished to Constantinople.

The Orseoli had however created many links between their family and the ruling dynasties of Europe who reacted to the deposition by taking several measures of retaliation against Venice. Several cities of Dalmatia were lost to Stephen I of Croatia and the future of the Republic seemed bleak for the first time in years. The new doge quickly lost the support of its people who deposed him and turned to the exiled in the Byzantine capital Otto Orseolo, who died however of natural causes before he could return to the ducal throne, in 1032. Domenico Flabanico, a popular and wealthy merchant of no noble ties was chosen to pull Venice from the brink of collapse but he was not able to reverse the descending spiral which would only stop thanks to his successor, the 30th Doge of Venice, Domenico I Contarini.

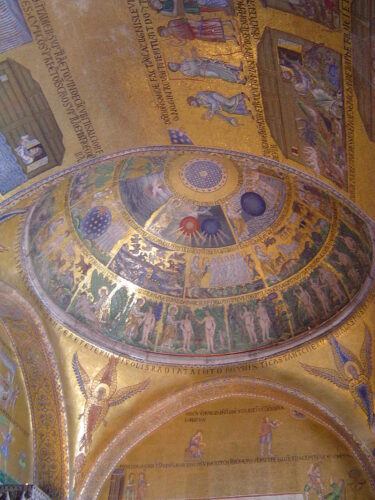

During Contarini Ι’s reign Venice recaptured Zadar and other parts of Dalmatia that had been lost to the Kingdom of Croatia, the Venetian navy grew exponentially and the economy entered a virtuous cycle. Contarini was also a great builder with iconic landmarks such as San Nicolò al Lido, Sant’Angelo della Polvere and St. Mark’s Basilica entering a phase of further expansion.

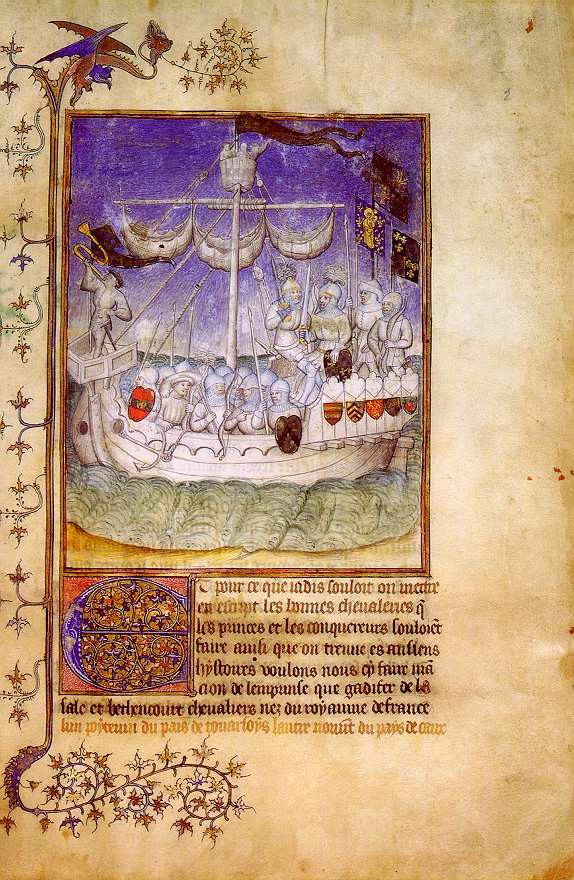

After an almost 30 year-long term Domenico Contarini was buried at the church of San Nicolò al Lido in 1071. After the funeral “an innumerable multitude of people, virtually all Venice” (according to an eyewitness parish priest named Domenico Tino) assembled outside the new monastery church in their gondolas and armed galleys to voice their opinion on the selection of a new Doge. The bishop of Venice asked “who would be worthy of his nation” and the crowds chanted the name of their preferred leader, “Domenicum Silvium volumus et laudamus” (We want Domenico Selvo and we praise him).

According to Venice’s tradition the Doge-elect (who had probably gained his popularity during Contarini‘s term) was lifted above the cheering crowd by a group of distinguished citizens and was carried barefoot into St. Mark’s Basilica, still under (re) construction then, where he prayed to God, received his staff of office, heard the oaths of fidelity from his subjects, and was legally sworn in as the 31st Doge of Venice (Spring of 1071). During the first 10 years of his reign, Domenico Selvo proved to be as capable as the cheering crowds of Venice hoped he would be. On the western front he managed to balance perfectly between the two opposing camps, Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV . On the east (Byzantine Empire) he would cope even better, by marrying the sister of the reigning emperor, Michael VII Doukas in 1075.

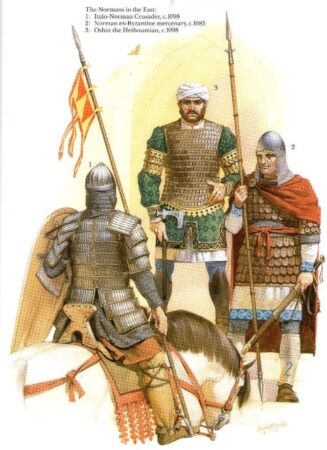

In May 1081 Domenico Selvo would become a hero after crushing the Norman fleet of Robert Guiscard (conqueror of Southern Italy & Sicily) in Dyrrachium, a victory which not only fended the maritime Republic against the possibility of a Norman control of the Adriatic sea but also granted Venice and its merchants many privileges and tax exemptions from the grateful Byzantines who had asked for the Venetian help in the first place.

In the apogee of his popularity Selvo would make the common mistake to underestimate his opponent. Despite the fact that the Norman fleet had already been defeated not once but three times by Selvo‘s fleet, it managed to regroup and organize a counterattack that caught the Venetians off-guard and cost the lives of about 3.000 of them, with 2000 more being taken prisoners. Nine great galleys, the largest and most heavily armed ships in the Venetian war fleet, were lost as well. The sudden shock for the Venetian people and their firmly established self-confidence was simply too big for the head of their governing body to remain unaffected. Domenico Selvo was held accountable and was stripped of all officia. Despite his discredited exit, Selvo had managed to open the gate for Venice to become a Mediterranean trade power, based on the privileged commercial relations that continued long after his removal in 1084. His legacy would echo for centuries in Venice’s most important landmark, St. Mark’s Basilica, which acquired much of its current shape during his term.