Grown Up

In 1541 a fire on Hradcany Square would spread quickly through the largely wooden houses to many sections of Malá Strana and Hradcany completely destroying large parts of those districts including a great part of the castle. Ferdinand I would introduce the Renaissance & Baroque styles in the reconstruction of the wounded towns with prime examples those of the Belvedere Palace & the Royal Gardens both in the vicinity of the Prague Castle.

In 1547 Prague spearheaded the nobility’s uprising against Ferdinand I after the King’s order to the Bohemian army to move against the German Protestants. Ferdinand was a supporter of the Counter-Reformation which he believed was essential in order to curb the Heretical tide of Protestantism. After suppressing the revolt, Ferdinand retaliated by limiting the privileges of Bohemian cities and introducing a new cast of royal officials that would control the city councilors. He also invited the Jesuits to Prague (1556) and revived the Archdiocese of Prague which had been null for some years (1561).

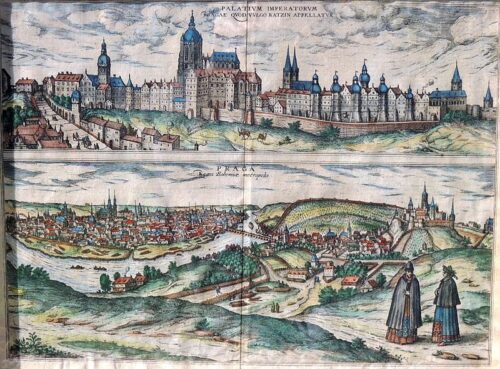

A new bright era started for the city at the time of Ferdinand I’s grandson, Rudolf II (Born 1551, King of Bohemia 1575-1611 & Holy Roman Emperor 1576-1612). In 1583 Rudolf II moved the imperial court from Vienna to Prague & Prague Castle became the Emperor’s permanent residence after the needed works on the building which was expanded to the north. The majestic Spanish Hall was added to the ensemble for the emperor’s impressive art collections.

Rudolf II was a great patron of arts and one of the most important art collectors of all time, especially in works of Northern Mannerist style. His spectacular collection of art & curios was partly inherited by his family and partly given to him by various diplomatic delegations and scientists. Its greatest extent though was purchased by him through his agents abroad.

Rudolf also invited artists to come and work in Prague, he supported them to live and create and soon Prague became an artistic hodgepodge. Rudolf acquired the reputation of a generous patron of the arts and Prague became an obvious port of call for many wandering artists.

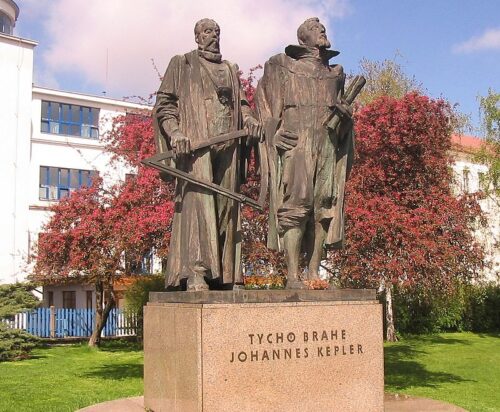

The emperor did not only transform Prague into the European Mecca of arts & the political epicenter of the continent, he also made it a main attraction for scientists, especially those who specialized in the so called occult sciences. A fervent fan of Astrology (Nostradamus himself had prepared a horoscope especially for him) & Alchemy, Rudolf made his lifelong quest to find the Philosophers’ Stone & spared no expense in bringing Europe’s best alchemists to court.

In his extensive cabinet of curiosities in the northern wing of the castle, a whole micro-cosmos of minerals, plants & animals were displayed alongside the newest scientific instruments of the era. Rudolph even performed his own experiments in a private alchemy laboratory.

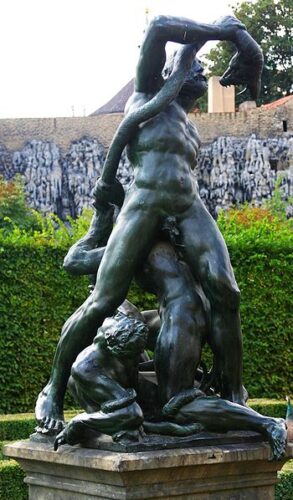

The mystic Parnassus of the Arts was a city where astronomers like Tycho Brahe & Johannes Kepler, alchemists like John Dee, painters like Giuseppe Arcimboldo & sculptors like Adriaen de Vries, co-existed with musicians, , philosophers, poets, magicians and astrologers in what became one of the most interesting melting pots in European history.

In 1609, the emperor would give one more reason, the last of his reign, to Praguers to hold a special place for him in their hearts. In his Letter of Majesty Rudolf II granted religious freedom to his Bohemian subjects & created a Bohemian Protestant State Church, in a move unprecedented in Europe at that time.

Despite his bold move, Rudolf’s concessions were judged as unsatisfactory by the Czech Protestants who appealed to the emperor’s younger brother Matthias for help. Matthias’ army then held Rudolf prisoner in his castle in Prague, until 1611, when Rudolf was forced to cede the crown of Bohemia to his brother.

Rudolf II’s death in 1612 marked the official ending of the most glorious period in Prague’s history, the end of Rudolfine Prague that would be immortalized by the loads of artwork and the series of surviving buildings of the old city. Soon Rudolph’s collections & court entourage were largely dispersed. Matthias extended the religious concessions to Bohemian subjects prompting many Protestants, mostly German to move into Bohemia & Prague.

Things would change dramatically when the next Habsburg in line, took over the helms of the kingdom in 1617. An inflexible Catholic & proponent of the Counter-Reformation, Ferdinand II was elected king by the Bohemian Diet, when his childless cousin Matthias fell ill earlier that year.

The predestined tension between the two sides wouldn’t take long to unravel. In 1618 the new king, forces the ailing & practically powerless Emperor Matthias to order the stopping of the construction of several Protestant chapels on royal land. When the Bohemian estates protested against this order, Ferdinand II had their assembly dissolved.

In May of 1618 Ferdinand II sent two Catholic councilors as his representatives to Prague Castle. On the 23rd of that month, the members of the dissolved assembly of the three main Protestant estates gathered at the meeting hall of the Bohemian Chancellery. Soon after, the two Regents were thrown out of the third floor window along with the Regents’ secretary in what is known as the Second Defenestration of Prague that would open the curtains of the Thirty Years’ War.

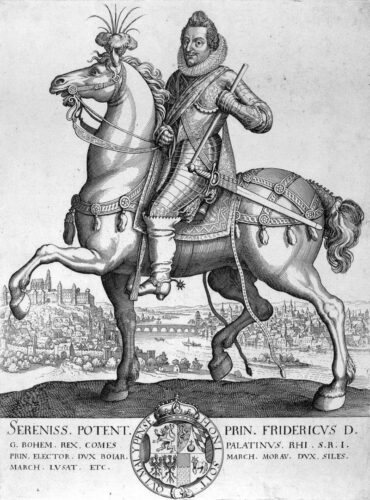

Events started to take the course of a snowball effect as the two sides (the Protestant Estates & the Catholic Habsburgs) counted their allies for war. Ferdinand strengthened his position by typically taking Matthias place as Holy Roman Emperor, after the latter’s death in 1619, with the Protestants answering with his deposition from the throne of Bohemia & his replacement by the Calvinist Frederick V, Elector Palatine.

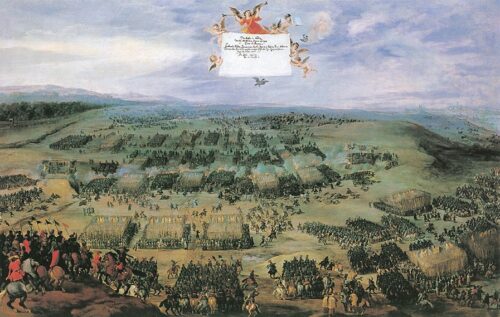

Because the Protestants had deposed a properly elected king they were not able to succeed in the formation of a significant alliance for war as opposed to the Catholics who managed to win the support of Catholic Spain, Poland & Bavaria, of Austria and Protestant Saxony in what became an unequal contest. On 8 November 1620 in the Battle of White Mountain just outside the city of Prague the Protestant army of 15.000 mostly Bohemians was crashed by the 27.000 men of the Catholic Imperial army in a battle that sealed the fate of the Czech Protestants for the next 300 years.

The victorious imperial army entered the defenseless city of Prague while King Frederick V with his wife and a number of estate politicians left the country. He would remain known as the Winter King (he ruled for just one winter). Emperor Ferdinand II became King of Bohemia & immediately ordered the imprisonment of the remaining leaders of the insurrection.

Forty-seven of them were put on trial & twenty-seven were executed (12 beheaded & 15 hanged) in the Old Town Square of Prague (27 crosses have been laid into the cobblestones as a tribute to those victims, at the exact point of execution). The heads of the beheaded were put on display on the Old Town Bridge Tower. The Bohemian Catholics rejoiced with the restoration of Roman Catholic rule while the execution was followed by reprisals against Protestants throughout the city and the country.

The penance fell hard on the shoulders of the defeated who had to convert to Roman Catholicism the official state religion or leave the country. All lands & properties of the Protestant leaders and their supporters were to be confiscated & returned back to the church or the crown. An estimated five-sixths of the Bohemian nobility went into exile soon after the battle. Prague had entered its doba temna (Dark Age).

Czech national identity was sidelined in favor of a general Germanization in the content of the whole Counter-Reformation wave that swept the country. A major campaign of re-conversion to the Catholic faith was taken on by the newly elected Archbishop of Prague Ernst von Harrach who was also appointed Chancellor of the University of Prague. The University was in essence merged with the Jesuit Academy. The entire education system was placed under Jesuit control while all non-Catholic priests were expelled by a royal decree.

The void left by the displaced local nobility was almost entirely filled by a new wave of German immigrants, this time Catholics from the southern German territories. They received most of the confiscated land & became the new ruling nobility.

In the context of the Thirty Years’ War between Protestant and Catholic states (1618 and 1648), Prague itself was taken over two times, first by the Protestant Saxons (1631 to 1632) and again by the Protestant Swedes who managed to seize Hradcany but were repulsed on Charles Bridge before reaching Staré Mesto (Old Town) in the Battle of Prague of 1648, the last act of the Thirty Years’ War.

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 would end a devastating war for the Bohemian Kingdom which was officially incorporated into the Habsburg Imperial system. The seat of the empire was moved from Prague to Vienna, giving another powerful blow to the wounded Czech capital, which would fall into a state of a provincial decline in the following years.

The disaster that hit Prague after the battle of White Mountain was portrayed in a very clear way, in the city’s population that fell from 60.000 in 1620 to 20.000 in 1650. Another outburst of the whole ominous momentum came in 1689 with a great fire that burnt down great parts of the Old Town, of the Jewish district & the adjoining areas with the gloomy epilogue written with a plague epidemic that wiped out more than 12.000 of the city’s inhabitants in 1713-1714.

Despite all the setbacks Prague saw a serious inflow of people, especially of Jewish descent, in the second half of the 17th century, pretty much related to the danger posed by the Turks in the south and the expulsion of Jews from Vienna in 1670. In addition the large fire of 1689 became the cause that spurred a wide range of restorations which beautified the city’s image and introduced it into the new fad of Baroque architecture.

In 1723, Prague would witness the most elaborate festivities of its history, on the occasion of Emperor Charles VI’s coronation as King of Bohemia in a series of ceremonial shows that were remembered for many decades by the people of the city.

The Emperor stayed in Prague for two months during which the Baroque sense of pomposity reached its apogee in a program filled with theatrical & musical festivals, feasts and processions of the court around the richly decorated streets.

A year later Count Sporck, a leading nobleman of German ancestry would open the first public opera house of Prague in his palace, where a series of Italian operas were produced regularly, attracting some of the most prominent singers & composers (among them Antonio Vivaldi himself, who visited Prague in the early 1730’s) from Italy to Prague, contributing a great deal to the spread of opera in central Europe.

The accession of Maria Theresa to the imperial throne in 1740 would implicate Bohemia in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and bring the foreign armies in Prague, three times in only few years. In the night of 25/26 November 1741, the Franco-Bavarian troops manage to take Prague by surprise and proclaim Charles Albert of Bavaria King of Bohemia at the beginning of December of 1741.

At the end of 1742 the Austrians manage to recapture the city after a siege that first took place in June and then again in December. The latter managed to drive out the French forces that held Prague. Finally in the summer of 1744, after two weeks of havoc wreaking bombardment by the Prussian artillery, the commander of the defending Austrian army, signed a surrender and King Frederick the Great of Prussia with his generals entered the city of Prague which changed hands once more.

The city was plundered by the Prussian soldiers and in the same time it was forced to pay high war contributions and deliver food and horses to the occupiers. By the end of the year, the pressing Austrian army led the Prussians to the exit. The trampled Praguers channeled their frustration towards the Jewish population after a rumor of their alleged collaboration with the Prussian army.

The rumor was endorsed by Maria Theresa herself who sent a decree from Vienna ordering the expulsion of all Jews from Prague. Although the decision was revoked three years later it inflicted a severe blow to the well established Jewish community of the city that had climbed to a percentage of 30% of the total population and was the second largest in Europe after Thessaloniki up to that point.

In 1756 Prussia’s war against the Austrians was renewed for a third time, with King Frederick of Prussia marching an army of 100.000 to Prague. In the Βattle of Prague οn 6 May of 1757 that took place in the village of Šterboholy part of the metropolitan area of Prague today, the Prussian army managed to win a Pyrrhic victory & take Vítkov Hill.

In the second bombardment of Prague by the Prussian artillery, more than one quarter of the city was destroyed & St. Vitus Cathedral was heavily damaged. Despite the relentless fire the city held until the siege was finally lifted under the pressure of an Austrian relief army that victoriously fought the Prussians at Kolín, not far from Prague, on 18 June 1757.

After 1757 things started looking better for Prague. The city entered an era of economic progress mainly due to the mitigation of the guild restrictions and the new mercantile policies implemented by Maria Theresa. Her policies managed to increase commerce and steer Prague’s baby steps towards industrialization. The disbanding of the Jesuit order by the Queen in 1773 was another significant that not only removed the tight Jesuit grip, it also liberated their significant wealth that could be now reclaimed by the government for the benefit of the people.

Cotton weaving facilities, paper mills and copper workshops developed very quickly creating the need for working hands, catapulting the city’s population from 50.000 in 1754 to 78.000 in 1784. New grandiose palaces like Kinský Palace were built to house the thriving merchants and new landmark buildings like the Nostitz Theatre (later Estates Theatre) lined the city’s streets.

Maria Theresa’s liberal policies, especially in religious matters, were to a great extent influenced by her son Joseph II, who became emperor & co-regent (of the Austrian domains), after the death of his father in 1765. Raised with the writings of Voltaire and the Encyclopédistes, Joseph II was a proponent of enlightened absolutism.

Very often Joseph went against the decisions of his narrow-minded mother in a number of occasions. A few months after Maria Theresa’s death, on October of 1781, the people of Prague are announced the Edict of Tolerance according to which, Lutherans, Calvinists & Orthodox were granted equality before the law and freedom to privately exercise their religious beliefs.