Montmartre

If you have already visited Paris sometime in the past then there’s a big chance Montmartre is the first place that pops into your mind when you hear the name of the city of lights. One that has not visited yet would argue that with Eiffel Tower and Louvre on the list that’s a bit far-fetched. Everything considered though, Montmartre has everything you’ve imagined of meeting in the French capital.

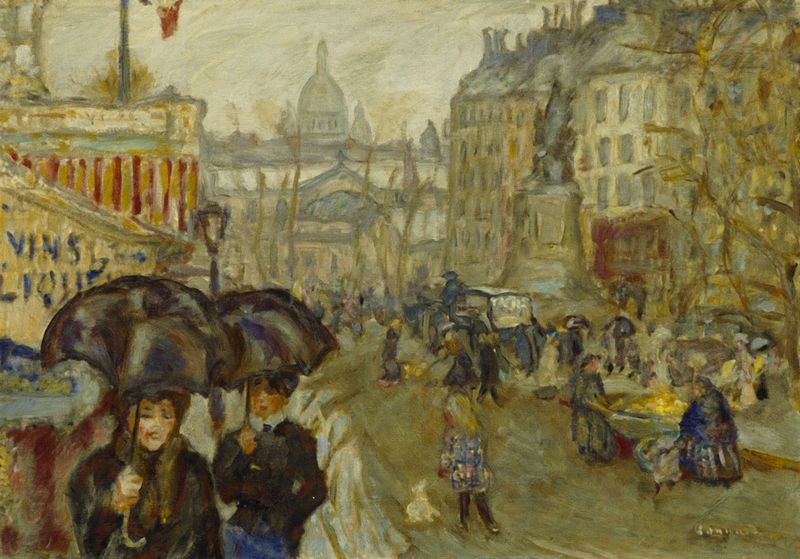

Spectacular views, narrow cobblestone paths, cute little cafes and bistros, picturesque window pane houses, street artists of all sorts, and painters. Lots of painters will gladly sketch your portrait or your caricature if you feel like it. Yes maybe it is too touristy but then again isn’t everything worthwhile these days?

So what was Montmartre and how did it come to be a cool bohemian hub? Back in the time of the Romans (according to some 8th-century texts), the Montmartre hill was used for religious purposes, probably for the worship of the Roman god of war (Mars). When the first apostles of Christianity came in around 250 AD the Gallo-Romans didn’t exactly greet them with open arms. One of the apostles was St. Denis, the city’s first patron saint, who along with his fellow missionaries was decapitated on the hill of the bloodthirsty Roman God. When Christianity finally triumphed in Paris the mountain became known as Montmartre (The Martyr’s Mountain).

Two times in the course of history Montmartre became an artillery outpost, both of them from an enemy army. The first was during the French wars of religion when Henry IV used the hill during his siege of Paris in 1590 and in 1814 when the hill was occupied by the Russians during the battle of Paris. After the disastrous outcome of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 and thousands of dead French, the collapse of the 2nd French Empire and the inauguration of the 3rd French Republic there was a call for unity between secular and religious institutions, for an expression of penitence, trust,hope and faith. The building of an impressive new basilica would crown the highest point in the city. The Basilica of Sacré-Cœur began in 1875 and was completed in 1914. Its white limestone and unusual Romano-Byzantine style stand in great contrast to the Gothic and Baroque-style churches that dominate the rest of the city.

The contrast of Montmartre with the rest of the city is not just confined to Sacré-Cœur. Up until 1860, Montmartre was a different town. Its distance from the core of the city kept its rural character unspoiled and the cost of living relatively low, a trait that in the latter half of the 19th century attracted the bulk of the city’s artists and painters who were mostly struggling to make a living. Montmartre became the bohemian neighborhood of Paris. It was where Monet, Dali, and Picasso met for a drink and sometimes even paid with their paintings.

Of course, the situation today is another story. There are few Montmartrois left and most of them feel like they’re being chased out by high rents and swarms of tourists that flock to the famous hill every day. Hence the rumor of a rude manner that still accompanies the veterans of Montmartre. To add to the artistic atmosphere Montmartre is home to the Musée de Montmartre, a museum that was once a common meeting place for many artists and writers, today an inspirational place that oozes Parisian charm and 19th-century history.

Then there’s the Musée de la Vie Romantique for the incurable romantics with a cute tearoom in the garden’s greenhouse for the sunny months of the year. Then there’s the Musée d’Art Naïf Max Fourny for modern art lovers and of course the Dali Museum, the only place in France entirely dedicated to Salvador Dalí. Let’s not forget Moulin Rouge, the greatest cabaret that ever existed.