Grown Up

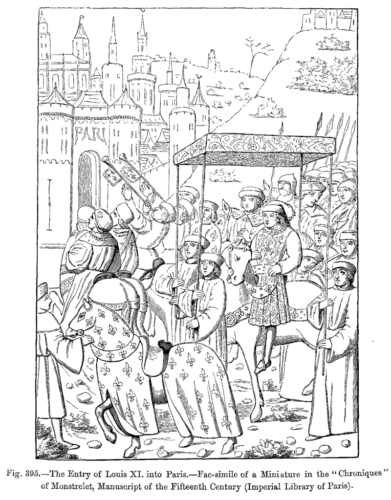

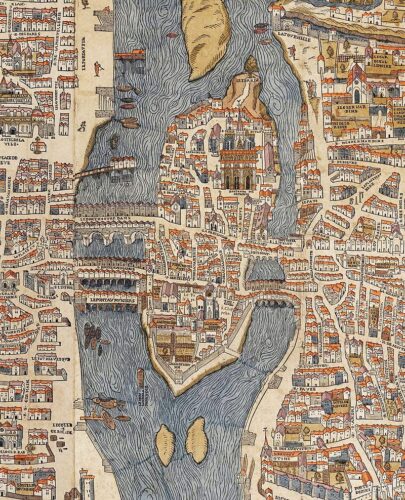

By the year 1500 the population of the city had bounced back despite the frequent visits of the plague and the occasional outbursts of famine that claimed the lives of thousands in one fell swoop like the one in 1481. Overall the country enjoyed a period of growth and prosperity in the second half of the 15th century but the Valois didn’t bother much with their unhygienic and capricious capital. They did pay a visit from time to time but their main concern and consumer of time and money were their new affairs in Italy. The only noteworthy addition from that era to the cityscape came from the monastic Order of the Cluny (Hotel de Cluny built from 1480 to 1510) not the kings.

Their involvement in Italian matters brought the kings of France in contact with the rich Italian culture in a time of profound intellectual proliferation and artistic revival but it wasn’t until the reign of Francois I (r. 1515 – 1547) that France actually got a taste of the European Renaissance. A man of striking stature and impeccable taste, Francis Ι, pursued beauty in every expression of his personal aesthetics, be that in his impressive wardrobe , his female entourage, his passion for art or his landmark building projects. In contrast with his predecessors Francis I could grasp the importance of the cultural movement taking place in Italy and appreciated it enough to try to import it into France through architecture, patronage of emblematic Italian artists like Leonardo Da Vinci and of course education and literacy.

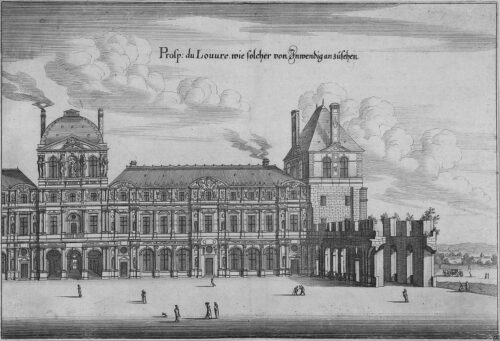

It was a most fortunate occasion for the city that unlike his predecessors, this Renaissance king, happened to like Paris enough to make it his personal residence. When Francis I declared his intention to move back to Paris in 1528 the old royal palace on the Île-de-la-Cité was occupied by the Parliament of Paris, so he decided to make the grim fortress of the Louvre, a modern Renaissance palace. Although he would not live to see the Louvre finished the king would go on in the construction of seven different palaces, most of them around Paris, with his favorite being the Château de Fontainebleau about 55 kilometres (34 miles) southeast of Paris. All seven of them are prime examples of French Renaissance style.

As a true philomath who had the privilege to live along Leonardo Da Vinci during the masters’ latter years, Francis couldn’t help but being a lover of books and didn’t spare any expense when it came to his own collection. His agents scoured Italy for rare publications and later he demanded his library be given a copy of every book that was sold in France. He then opened the royal library to all scholars in order to facilitate the diffusion of knowledge. In 1470 the first printing press had been installed at the College of the Sorbonne. By the time of Da Vinci’s death in 1519 Paris had surpassed Venice as the printing and publishing capital of Europe. In 1530 Francis declared a standardized version of French to be the national language of the kingdom and later that same year opened the Collège des trois langues, where students could study Greek, Hebrew and Arabic.

Francis I was also the one who established the first collection of artworks that would later be exhibited in the Museum of the Louvre. Besides Leonardo he was a friend of a number of great artists like Benvenuto Cellini (a goldsmith, sculptor, musician and poet of immense talent), Rosso Fiorentino (an Italian Mannerist painter of the Florentine school) and Giulio Romano (a pupil of Raphael). Most of these artists were employed in the decoration of the king’s palaces.

Another long-lasting contribution of Francis I was the financing of a new City Hall, one that would signify the transition to an era of greatness. Hôtel de Ville was built in the place of an older city hall built by Étienne Marcel in 1357 into the square of Place de Grève, that was henceforth renamed into Place de l’Hôtel de Ville (City Hall Square). Again the king would not live to see the Renaissance building finished (1628), nonetheless his gift to the city still operates according to its original purpose to this day.

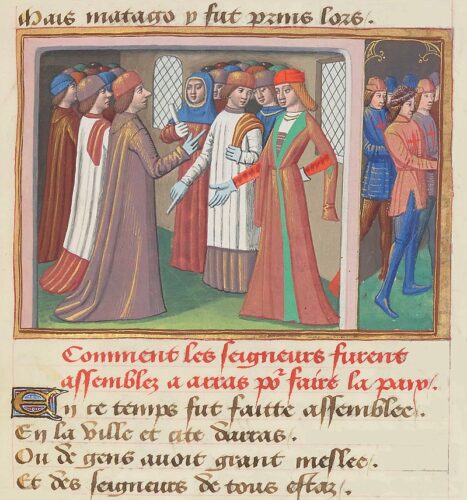

Looming under the surface of the Renaissance projects during the years of Francis I’s reign was a new conflict that would shake the foundations of his kingdom and thrust Paris into another trance of bloody rivalry. When Martin Luther’s preaching and writings started spreading sparking the Protestant Reformation (after 1517), Francis I saw in the religious movement nothing but a convenient nuisance that plagued the enemies of France. Charles V and Francis I were sworn enemies with conflicting interests so when a number of German princes started turning against Charles V, the new religious trend was in reality useful for the French King. It was when the activism of the fervent reformers reached his doorstep, (Affair of the Placards, 1534) that Francis I changed his attitude towards Protestantism mainly due to his fears that the French movement would turn out to be a threat to his own status. The first persecutions of Protestants officially started after 1535 with the burning of heretics in front of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, the suppression of printing freedom, with exiles and executions of non-Catholics. A former militaire 40-year-old Basque theologian, was at that time of religious upheaval attending the famous Catholic University of Paris. On the 15th of August, 1534, in the crypt of Saint Denis, at Montmartre, Ignatius Loyola and his six companions, of whom only one was a priest, founded the Jesuit Order that would very soon become the flagship of the Counter-Reformation.

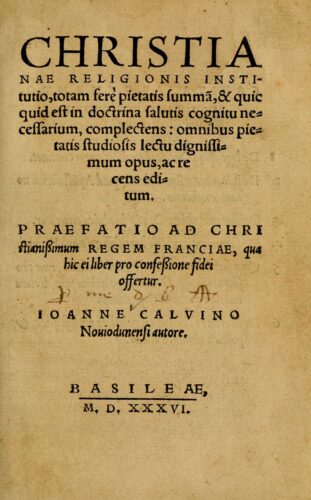

In the beginning Protestantism was mostly followed by the lower classes of France but after another student from the University of Paris, John Calvin published his book Institutio Christianae religionis in 1541 (in French language) an increasing number of nobles identified themselves as Calvinists. Although King Henry II (r. 1547 – 1559) would make things even more difficult than his father for Protestants, their numbers swelled to about ten percent of the general population by the end of his term. A clear manifestation of the general discontent for the Papal Church right before the religious wars.

After the accidental death of Henry II during a jousting match in 1559 at his residence at the Hôtel des Tournelles, things got more tense. Just before his death the king had ordered the arrest of all members of parliament calling for tolerance. His death made Paris a playground for the powerful Catholic family of the Guise. Henry II’s widow, Queen Catherine de Medici tried to juggle the opposing factions on behalf of her fifteen year old son Francis II with an aim to avoid another civil war and keep the Guises in check but when a group of Protestant nobles tried to kidnap young Francis II and arrest the Duke of Guise and his brother, the Cardinal of Lorraine, in 1560, (Amboise conspiracy) things got out of hand.

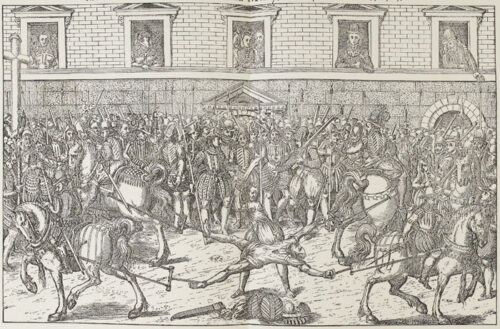

The civil war between the two factions officially started on 1 March 1562 with the Massacre of Wassy, where the troops of the Duke of Guise massacred 63 unarmed Huguenots and wounded a hundred more, holding a secret ceremony in a barn on the way to the Duke’s estates.

From then on, a vicious and in every way unholy war, steeped France in blood for more than 10 years. Protestants are massacred in several French cities and the Duke of Guise seizes the royal family in Paris. Louis de Bourbon Prince of Condé, leader of the Protestant side manages to capture Orleans, Lyon and Rouen and organize several assaults on the outskirts of Paris with the economic support of Elisabeth I of England and the military support of German mercenaries. However they do not succeed in Paris and are forced to fall back.

The Catholics with Duke of Guise take the initiative and recapture Rouen which is later submitted to looting and extreme violence. They then win the important Battle of Dreux and begin the Siege of Orleans where De Guise was killed by Jean de Poltrot de Méré, a former plotter in Amboise (a hand of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny according to most). The latter was captured and tortured on the Place de Grève in Paris. The war continued with frail little breaks of peace imposed in the initiative of Catherine de Medici who tries to impose a policy of tolerance on behalf of the crown until 1567, when the Protestants led by Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé tried to kidnap her and her son, Charles IX for a second time. (the 17 year-old Charles was king from 1561 when his brother Francis II died).

With the Catholics taking a clear upper hand and Admiral Gaspard de Coligny being on the head of the Protestant armies a new treaty of peace is signed that grants Protestants limited freedoms in certain cities but not in Paris. Being a Protestant in Paris remains illegal according to the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye signed in 1570 by the two parties. The Queen-mother and Charles IX make one last effort to reconcile the two sides. They defend the peace, they accept Gaspard de Coligny back to the royal council and arrange for a royal wedding between Princess Margaret (seventh child of Catherine de Medici and sister of Charles IX) and the Protestant Prince Henri de Bourbon (his uncle Louis de Bourbon had staged the last royal abduction) to be held in Paris in the summer of 1572.

There was however a key player in Paris, one that had every reason and interest to see the whole venture fail. The powerful family of the ultra Catholic Guise headed by the 22-year-old Henri I, already experienced in the field of battle against the Protestants and full of hatred from the time of his father’s assassination in 1563 by a man of Coligny (supposedly). Like that wasn’t enough the young Duke of Guise was in a relationship with Princess Margot who was initially intended to be his own bride. The wedding took place on August 18, 1572 in front of Notre-Dame de Paris so as not to raise issues that had to do with particular religious rituals and disputes.

After three days of sumptuous festivities, with the city still full of Protestants who had flocked to celebrate what they saw as an official peace pact, Coligny is nearly fatally wounded outside the Louvre from a gunshot that came from a house belonging to the Guises. The horror that followed is known as the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, in which as much as 3.000 Protestants were slaughtered, regardless of age, sex or status. Although no proof or written document was ever found pointing to the actual orchestrator, it seems that after the failed assassination of Coligny, Charles IX and the Queen mother made the decision to eliminate the Protestant leaders in fear of organised reprisals but the extent of the whole bloodbath was clearly not in their plans.

The war continued until the end of the century and the Edict of Nantes signed in 13 April 1598, that eventually put an end to the killings. Paris remained a forbidden land for Protestants even after the treaty despite the fact that after more than 30 years of warfare the majority of the people in Paris felt the need for a reconciliation, a fact proven by the expulsion of the Jesuit order and the rebellion against the leaders of the Catholic League (founded in 1576 by Henry I of Guise with a sole purpose the complete eradication of Protestants), even before the signing of the Treaty.

During the last years of the 16th and first years of the 17th centuries the throne of France was occupied by Henry de Bourbon, the same Henry whose marriage had triggered the most horrible event in Parisian history. Henry de Bourbon became King Henry IV when he finally converted to Catholicism in 1593. His successful reign, especially the first decade of the 17th helped France and Paris recover from the nightmare of the civil war. With the help of his trusted councilor Maximilien de Béthune the Duke of Sully, Henry IV implemented several reforms that revitalized trade, textile production and agriculture. In the same time he proved to be quite a builder with the enlargement of the Louvre and the Tuileries Palace, the building of the Gobelins Tapestry Factory, the completion of the Point Neuf, the oldest Paris bridge in existence today and the construction of several new squares like the Place Dauphine.

Despite all his work, Henry IV was stabbed to death by a fanatic Catholic on May 13, 1610 at 8-10 Rue de la Ferronnerie (close to today’s Centre Pompidou) in Paris. Up to his death the king had managed to survive at least twenty assassination attempts. His son and heir Louis XIII was a bit younger than 8 years old at the time of his father’s death so the Regency passed to his mother, Marie de’ Medici, who would rule France until her son reached his fourteenth birthday. Marie de Medici, Henry IV’s second wife after Queen Margot, was the sixth daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, born and raised in Palazzo Pitti in Florence. With the city still under shock from the new regicide and most people fearing that an outbreak of a new civil war is imminent Queen Marie makes a cunning strategic move with a double Franco-Spanish wedding that buys her precious time and strengthens her position with a mighty ally. To appease mounting Protestant fears for a new Saint Bartholomew’s day she had previously re-affirmed the Edict of Nantes in a move of equal importance.

With the royal coffers full from the wise policies of Duke Sully and the rebellious princes generously compensated in order to stay loyal, Marie felt safe enough to do what all kings of France did when they felt thus. She built herself a new palace. In 1615, three years after her lavish festival at Place Royale, her late husband’s last endowment to the city of Paris, on the occasion of the double royal engagement, the Queen mother placed the foundation stone for her Florentine-like palace (Palais Luxembourg) on a remote piece of land on the left bank, that would make her feel like home. French architects were sent to Florence to make detail drawings of Palazzo Pitti, the greatest palace of her home-town, a Florentine fountain-maker took on the task of an impressive Italian Renaissance style fountain (Medici fountain), the most famous artist of the time, Peter Paul Rubens was brought in to decorate the interior and the gardens were modeled after those of the Boboli Gardens in Florence. There was just a petty detail that the builders had to overcome. The land on the left bank (where the university and religious institutions were located) did not have the needed water sources for such a project. Wells were the only source of inland water then, and these were easier to dig in the softer ground, on the other side of the river. That was the reason why the left bank was still then, less populated compared to the right. The restoration of the ancient Roman aqueduct and the construction of a new 13 km underground water conduit with several Regards (little stone houses that provided access to the running water) in-between, made the Palace of Luxembourg the new pride of the court and the left bank the new hot-spot for the Parisian nobility.

For three years the Queen mother refused to be sidelined and let Louis XIII exercise his rightful royal duties. By 1617 the pubertal impatience of the dauphin had grown into a full-fledged indignation. In a move that did not fall far short from a Coup d’état, the palace was raided, the closest advisers of the Queen mother like Léonora Dori arrested and executed as enemies of the state and Queen Marie herself banished from court. It was a showy maneuver of emancipation for all Paris to know. Louis XIII would now be the king and nobody, not even his mother could stop that. The young of his age did not prevent Louis from acknowledging the need for competent associates. His unfortunate first choice in the face of Charles of Albert , Duke of Luynes was more than rectified with the placement of Cardinal Richelieu, an ingenious and broadly educated bishop and statesman in the head of the government. Richelieu had been in Queen Marie‘s close circle and was the one who reconciled Louis XIII with his mother right before the outbreak of a new civil war. As opposed to Louis XIII who showed more interest for hunting and battles against revolted (Protestant) provinces, Richelieu was more interested in the affairs of Paris and passed as much time as he could in the city.

Richelieu’s wits made many historians come to the conclusion that it was he who actually ran the whole show and not the king. Especially after the conquest of the last Protestant stronghold, the city of La Rochelle, where Richelieu showed exceptional military skills he was literally impregnable. When the time came for the king to make a choice between his mother (their tumultuous relationship surely played a role) and Richelieu, the king chose the latter (1630).

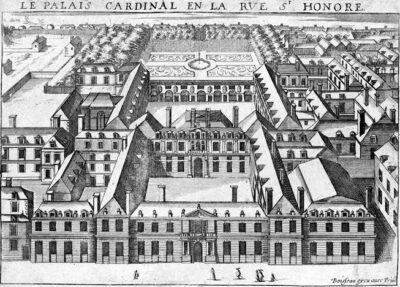

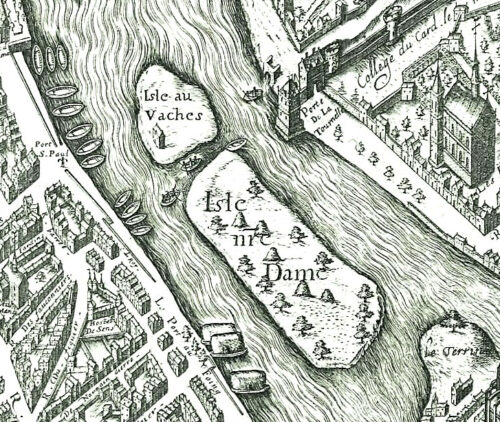

With the official royal residence being the Palace of the Louvre since the early 1580’s and Richelieu being equally perceptive in matters of real estate as well as politics, a vast property that stretched opposite to the north wing of the Louvre is bought and divided by him into lots. On the west side of the property Richelieu builds his own palace, the Palais Cardinal, that is bequeathed to the king and becomes Palais Royal after his death in 1642 (today it is the house of the Ministry of Culture and the Constitutional Council of France). The rest of the lots become the new favorite neighborhood of government officials and members of the royal council. The cardinal’s architectural mark on Paris was further expanded with the creation of four new bridges over the Seine. Two of them, the Pont Marie and the Pont de la Tournelle are built to join a new island, the Île Saint-Louis, to the Seine’s banks. The Île Saint-Louis can be credited to Richelieu, since most of the project was carried out during his government but in reality the plan for the creation of the island belonged to Henry IV . It was financed by two private investors who reaped the benefits of its commercial exploitation when the once muddy pasture for cows was turned into the most charming showpiece of the capital (late 17th).

By the time of Richelieu’s death in December of 1642, the French throne was stronger than ever, the powers of the great noble lords had been curtailed, the Huguenots subdued and Paris had been turned into a model of Catholic renaissance. The Jesuits had resumed their role of educators, the clergy had regained respect and new sumptuous Churches like Saint-Eustache, the Sorbonne Chapel and Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis glorified the victory of the true faith. The great statesman had done everything in his power to secure that his king would be the envy of all kings and to a great extent he had succeeded. It was Richelieu who paved the way for the Sun King the true envy of every absolute monarch that followed. King Louis XIII died few months after Richelieu. Contrary to the caricature of their relationship based on Alexandre Dumas‘ novel The Three Musketeers the two men died with their beds side by side according to the orders of the king.

The Sun King, Louis XIV, was just four years old when his father died (1643), so for a third time in history the royal power in France passed to a woman’s hands, the Queen Mother, Anne of Austria. Once again a gifted clergyman was chosen as the head of state with a hope that he should follow on Richelieu’s footsteps. The Italian born Cardinal Mazarin was a trusted hand of Richelieu rumored to be in a secret relationship with the Queen with some historians even suspecting that he was the true father of the child king. Although France had stayed out of the Thirty Years’ War, the tension with the Habsburgs had brought the Spanish troops on the doorsteps of Paris twice in only few years. The undeclared war needed funding so taxes had to be maintained at a high level. In the same time Mazarin invented new ones, that affected both rich and poor. In 1648 Mazarin’s policies caused the outcry of the parliament. The Queen ordered the arrest of the leading dissenters and soon after riots broke out across Paris. Barricades of chains were set up in hundreds of streets demanding the release of their representatives and the houses of Mazrin’s associates were attacked. The Freunders (from the word fronde which meant sling, like the ones used by the rebels to catapult stones) managed to take over the city and burst into the Palais Cardinal, now Palais Royal, demanding an audience with the 10-year-old king who had to feign sleep. Queen mother and Louis XIV had to flee Paris two times to avoid the humiliating house arrest.

In essence the fight would be given between those who wanted to have a word in economic matters and those who served the crown. At times the distinction between the two sides was not so clear, like in the case of Louis Grand Condé who started the standoff as a celebrated commander of the royal army but then changed sides and became the leader of the Fronde. In 1652 three battles were fought between the royal army and the army of the Fronde outside Paris and all three were won by the royals. The Parisians had had enough of bloodshed so in September they kicked Condé with his soldiers out and sent word to the king to return. Mazarin and Louis XIV returned to Palais Royal victorious at time when the young king had reached the needed age to assume his duties (14 y.old).

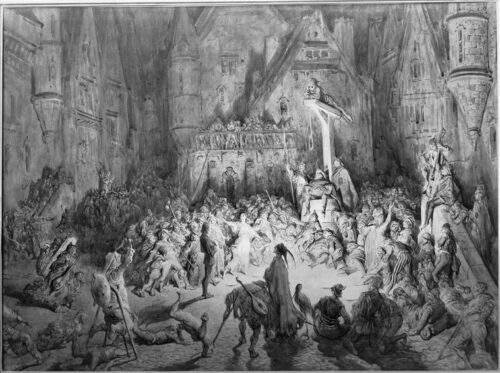

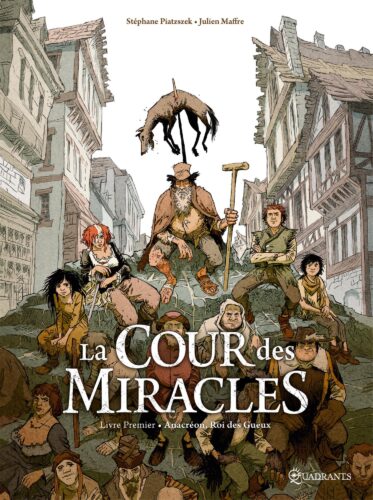

The ups and downs of politics didn’t seem to have an affect on the city’s overall population which increased exponentially from 300.000 in 1600, to 500.000 in 1680. With it came a rapid increase in the number of beggars, poor, homeless and desolate who scavenged the streets for an occasional work or a handout to make their living. Prostitutes and thieves were spread out all over the city, as were the slums where the poor lived in horrid conditions. Paris had about twelve of these slums in the 17th century when most European cities had one. The Cour des Miracles, or Courtyard of Miracles was an all-encompassing term referring to all the slums of Paris and the people who feigned various maladies in order to evoke sympathy but were miraculously cured when they returned to their “courtyard of miracles”. The term was invented by a 17th century Parisian historian named Henri Sauval describing in detail a whole world of outcasts who had formed a crooked society of their own, with its own casts, laws even language. That society of les miserables categorized its people according to the specific category of begging (some feigned illnesses, others war injuries etc) or thievery they where involved with. That parallel society even had its own king and court of dukes. The shocking details of Sauval‘s history became an inspiration for works like The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and Les Misérables , two of the most famous novels of Victor Hugo who lived in Paris in the first part of the 19th century.

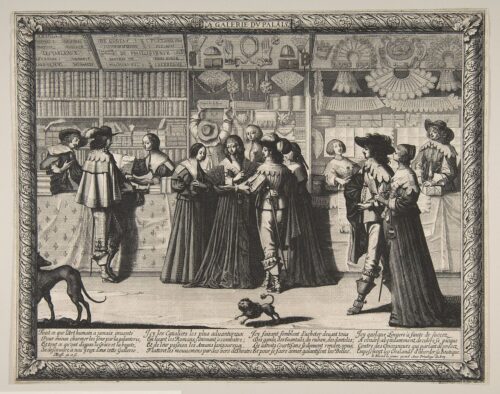

The survival of these vagabonds and of the lowest classes depended entirely on a constantly growing multilayered middle class of merchants and craftsmen, shopkeepers and employees , seafarers and well paid soldiers, painters and sculptors, pharmacists and tailors known as the bourgeois. A part of the bourgeois of Paris was constituted by state employees, more than 45.000 in the time of Louis XIV . The upper layers of the society were consisted of government officials, lawyers, magistrates, notaries and successful businessmen. Then there were the nobles and the members of the court. All these people had a refined taste in clothes, they sought for luxury goods and engaged in recreational sports like the Jeu de paume (an early type of tennis) and the billiards, watched theater plays by the Illustre Théâtre, the theater company founded by Molière in 1643. All classes, rich and poor marveled on the numerous architectural gems of the capital that was now adding to its extraordinary pallete, the new buildings of the so called Flamboyant Gothic or French baroque of the 17th century.

After 1652 the palace of the Louvre was completely redesigned, beautified and enlarged according to the wishes of the Queen mother Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin. The young Sun King continued his military training away from the city. He would return in 1660 to give Parisians a show like no other, a celebration for his wedding to Maria Theresa, daughter of Philip IV of Spain, a marriage that put an end to the wars with the Spanish after more than a century and a half. The spectacle of the impressive royal procession accompanying the royal couple through triumphal arches between the Louvre and Hotel de Ville would only be matched by the one given two years later for the birth of the king’s firstborn. At the head of a Grand Carousel, dressed as a Roman Emperor with the sun on his royal shield as his new emblem Louis stepped on Parisian self-indulgence to present himself as a mighty emperor of a new Rome that was Paris.

In many ways all the things that made him the Roi Soleil happened in these first years of the 1660’s. The integrity of France was secured giving him the freedom to shine, his chosen head of state Cardinal Mazarin died forcing him to take all matters into his hands, to be an absolute monarch, the flashy and spendthrift minister of finance Nicolas Fouquet whose sumptuous lifestyle sometimes over-shined that of the king himself was removed, Fouquet’s personal architect became the king’s master builder, the one who would transform the Versailles from a remote hunting lodge to the greatest palace the world has ever known.

Τthe work was still in progress at the Louvre when a great fire destroyed a part of the palace and led the court to the The Tuileries Palace from 1667 to 1672. During that period the king’s architects were simultaneously working in the restoration of the Louvre, the expansion of the Tuileries and the building of the Versailles. After 1672 although the work was far from over the court moved into the Versailles. Louis’ obsession with Versailles had started back in 1661. Up to his death in 1670 Louis Le Vau had barely managed to complete the apartments of the royal family. What was ready when the king moved in was a great part of the spectacular gardens, the Tethys cave, the orangery, the menagerie and the Apollo basin.

It wasn’t just the palaces that were being built in the time of the King Soleil. In fact the city experienced a building boom and improvement of day to day issues like never before. The Champs-Élysées and its gardens were laid out in 1667, the Paris Observatory built by 1672, the Hôtel des Invalides, a home for wounded soldiers inaugurated by 1674, the building of the Collège des Quatre-Nations, the most amazing hybrid of Baroque and Classical style was finished by 1688, the city walls built by Charles V and Louis XIII were razed to make way for the Boulevards Parisiens, the legendary grand boulevards of Paris were ready by 1705.

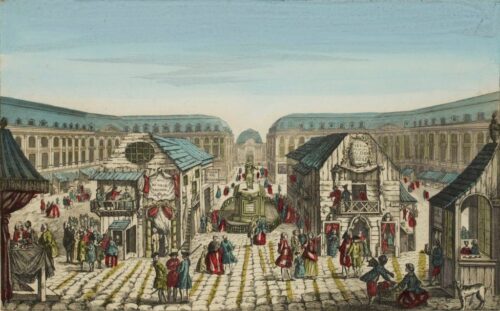

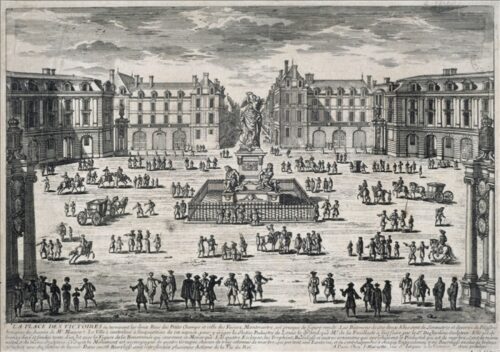

In the same time street lighting was introduced for the first in a large scale, making Paris a city of light (the term originates from that period) and the police force of the city was reorganized, the number of the city watchmen quadrupled, all men of every different security force were put under one umbrella, bringing the sense of safety in the crime-ridden streets of the capital for the first time in years. The hygienic and sanitary conditions were improved, new squares like the Place Vendome and the Place des Victoires offered a new set of open spaces to the Parisians and new triumphal arches like the Porte Saint-Denis and the Porte Saint-Martin celebrated the military victories of the Sun King.

Louis XIV died of gangrene in September of 1715. During his 72 year old reign (the longest recorded in history) the Sun King had managed to make France the envy of the world, admired for its military and cultural prowess, French became a universal language of the elite. Despite his distrust towards the Parisians since the events of his house arrest during the Fronde movement, he actually managed to give Paris what he had promised in the beginning of his reign, a stature and grandeur that had not been seen since the time of Ancient Rome. On the other hand, his misconceptions, his megalomania and bellicosity, his persecution of Protestants, his over-concentration of powers and his excessive expenditure set the foundations for a social upheaval that would lead to the French Revolution and the violent abolition of the monarchy in 1789.

Two years after the death of Louis XIV a young libertine writer named François-Marie Arouet is incarcerated in Bastille for eleven months after offending the new regime, the Regent Philippe II d’Orléans who had taken power in the name Louis XIV‘s five year old great-grandson Louis XV. The young libertine had been a frequent of a gentleman’s club known for its wit and secular skepticism. The bourgeois gentlemen drank and recited biting verses about the church and the court. When one of those verses reached the ears of the Regent, Francois was exiled. When the story repeated itself Francois was imprisoned in Bastille. During his imprisonment the young libertine adopted the name Voltaire and wrote his first play, Oedipus, an adaptation of Sophocles‘ tragedy Oedipus Tyrranus, that became an instant hit. It was the official beginning of a new age, the age of enlightened humanists like Voltaire, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Denis Diderot who questioned the traditional doctrines and advocated for the transformation of the social structure on the basis of scientific knowledge and empiricism. It was the Age of Enlightenment and Paris was at its forefront.

What went hand in hand with bright philosophers besides the new fashion of cafes (by 1720 and in just a few years there were about 400 in Paris) was not as luminous and auspicious as the name of the age implies. Frequent spells of bad weather and failed crops, in combination with the loss of the greatest part of the New World colonies to the British, along with the bankruptcy of the Royal Bank of Paris that brought a great number of the bourgeois to their knees, had created an explosive mixture of widespread poverty and disillusion with the royal regime which was increasingly cut off from the people inside its golden bubble at Versailles.

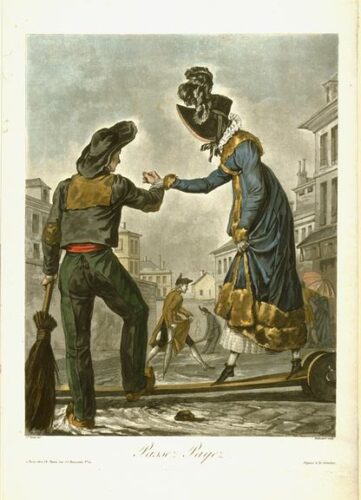

In the 30-year period that preceded the revolution there were some public works of a large scale taking place in Paris like the Square of Louis XV (now the Place de la Concorde), the Sainte-Geneviève church (the current Pantheon ), the Odeon Theater and the Halle aux blés grain marker but the scale of all of them put together was nowhere near the reality experienced during the golden years of the Sun King. There were of course great mansions and palaces built by Counts, nobles and rich like the Elysee Palace and the ones built by the aristocrats in Faubourg Saint-Germain, the most posh neighborhood of the era but these were in contrast with the majority of small and poor houses, built more and more on top of each other, sometimes six, seven even nine stories high, in order to house the ever increasing population (around 600.000 at the second half of the 1700’s). Both Voltaire and Rousseau describe the situation of the city center of narrow, dirty and foul-smelling streets as unhealthy, hideous and sometimes even barbaric.

When Louis XV died in 1774 the Parisians heaved a sigh of relief. The placards of protest that were habitually hang from the king’s statues and the gates of his palaces were not enough to quell the accumulated hatred caused by the prolonged wars in Europe and America, the consecutive military defeats in both fronts, the economic depression, the regressive tax system, the corruption and special treatment of the king’s entourage, the decadence and extravagance of the Versailles. The nightmare of famine constantly hovering over the head of the poor was sweeping through an increasing number of middle class and bourgeois at the time of Louis XV.

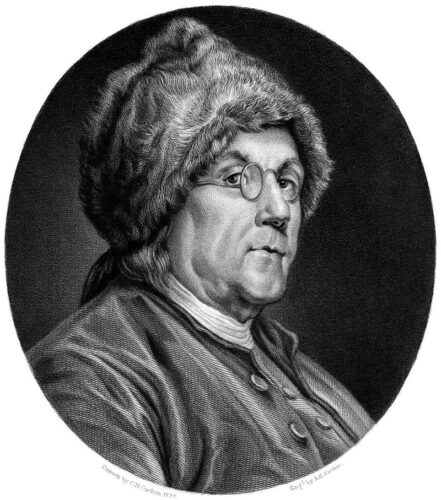

When Louis XVI ascended on the throne in 1774 the omens were bad. The experiment of the liberalization of agricultural markets, had backfired causing an increase of prices in grain for a number of years and Paris was not a grain producing region. A rumor had started to circulate that the government was deliberately trying to eliminate the poor by starvation. For 17 days nearly 180 conflicts were identified in the Paris Basin (Guerre des farines 1775) all related to the price of grain. The echoes of the American declaration of independence in 1776 did not seem that far away to the frustrated Parisians. That same year Benjamin Franklin became the first ambassador of the United States sent to Paris to represent the American government. The Treaty of Paris signed in 1783 ended the American Revolution and planted the final seed for the French that would follow six years later.

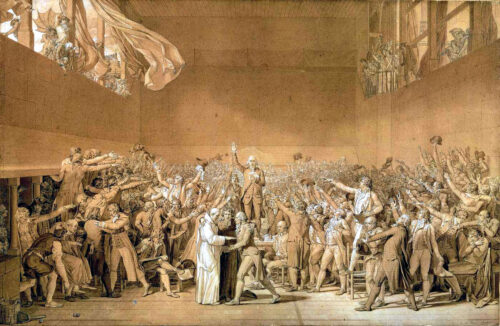

The winter of 1788-9 was particularly harsh. Trying to cope with the growing discontent and the danger of imminent bankruptcy Louis XVI accepted the convention of an Assembly of the Three Estates (the Clergy, the Nobility and the People) that had not taken place since 1614. The king and his finance ministers hoped that the assembly would help them bypass the rigid opposition of the nobility (hence the parliament) to bear a part of the huge royal debt through taxation. By June 1789, the Third Estate, that of the people, had formed a new body, the National Assembly and its members had taken an oath (Tennis Court Oath) not to give in until they had given France a constitution. On July 11, the King sacked his reformist Director-General of Finance Jacques Necker, a man who had advocated doubling the representation of the Third Estate. New rumors that the king meant to attack Paris or arrest the deputies sparked the first riots of the French Revolution.

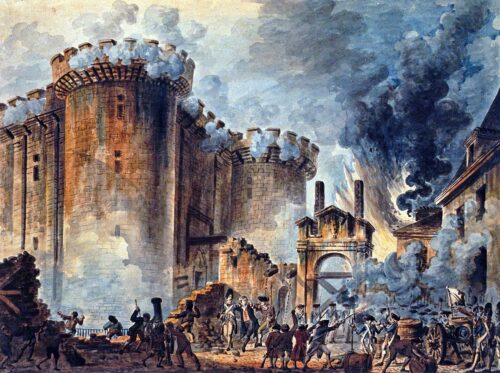

The Hotel de Ville and soon after the Arsenal at Les Invalides fell to the mob which was now armed with thousands of weapons but no gunpowder. More than two hundred barrels of it had been moved to the royal prison of the Bastille for safekeeping. The symbol of royal tyranny became an obvious next target and its walls were all that separated the milice bourgeoise from the control of the city. Within a few hours of a siege, about 1000 people, artisans, regular army deserters, even wine merchants, manage to take over the fortress defended by a little more than 100 veteran soldiers. The governor of the Bastille, the Marquis de Launay, who had surrendered the fort to avoid carnage, would pay it with his life. His head on a pike in front of the Hotel de Ville a retribution for the hundred dead attackers. Almost all of the soldiers were spared. The fort of the Bastille was taken down bit by bit and its prisoners released.

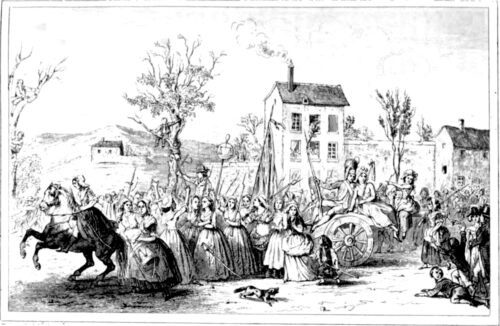

The Paris Commune, formed in Hotel de Ville after the storming of the Bastille was running things now. The new mayor, leader of the Third Estate and instigator of the Tennis Court Oath, Jean-Sylvain Bailly received the king at the Hotel de Ville who rushed to pay tribute to the new government and was presented with the new symbol of the revolution: the tricolor cockade ( red and blue, the colors of Paris, and white, the royal color ) under the cheers of the crowd. Despite the take over and the declaration of the groundbreaking Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen in August, the economy hadn’t changed, the grain prices had not gone down. Most workers spent nearly half their income on bread. In October a crowd worked up by the incendiary rumors of newly founded newspapers and persistent starvation, started a march from the marketplaces of Paris. The march was headed by a young woman striking a marching drum at the edge of a group of market-women who were infuriated by the chronic shortage and high price of bread. The march was joined by thousands and in about six hours it was in Versailles. The palace was stormed and Louis XVI with his unpopular Queen Marie Antoinette were forced to leave Versailles and move back to Paris and the Tuileries Palace. With the government and the king under the control of the National Assembly the first anniversary of the revolution was celebrated in July 1790 in a spirit of solidarity in the vast stadium of Champ de Mars where the king and deputies of the National Assembly took an oath in front of 300.000 Parisians to respect the new constitution. The grand feast that followed made everyone seem happy but what followed was not as civil.

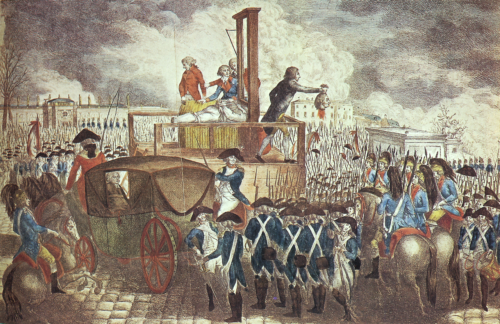

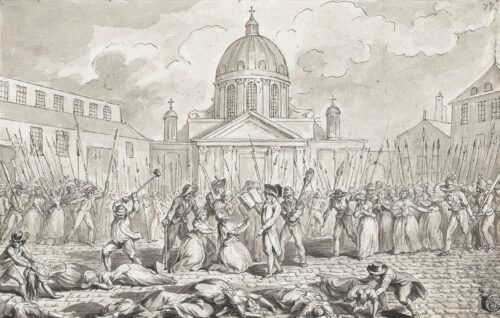

The people started to realize the true extent of their power and soon they were divided in three camps. The moderates rooting for a constitutional monarchy with the Mayor Jean Sylvain Bailly and the Commander of the National Guard (former milice bourgeoise), hero of the American Revolution, Marquis de Lafayette. The radical Jacobins, dominated by Robespierre and the most fervent and fanatic revolutionaries of all led by Georges Danton. Α wave of violence surged through the city with one faction fighting the other. Many aristocrats started to leave Paris. The members of the clergy were forced to take an oath to the constitution or leave the country, the Church property was confiscated. The King’s attempt to flee Paris sparked new rumors of a secret pact with the Austrians and the aristocrats, dozens of new libels gave vent to the rumors of treason and the lowest and most fanatic took over the government. The King with his Queen followed the hundreds that were executed as counter-revolutionists in what became a true reign of terror. Even leading revolutionists themselves like mayor Jean Bailly, Danton and finally Robespierre became the victims of the Committee of Public Safety that in Paris alone executed more than 2.500 people until the end of 1794. The first days of the republic were drenched in blood. Paris nothing but a gruesome theater of terror where the new invention of the Parisian deputy Joseph-Ignace Guillotin (the guillotine) was put to the test with as many as fifty executions a day.

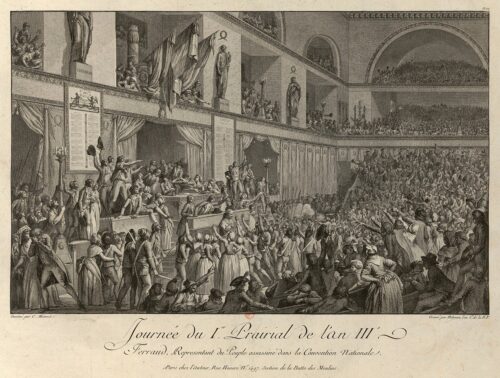

The fall of Robespierre put an end to the executions and the reign of terror. Appalled by the practices of many of their former comrades the republicans created a new form of government known as the Directory (le Directoire) . Its purpose to draft another constitution that would prevent the concentration of power in one person or executive body. The city of Paris was placed under the direct control of the national government given its crucial role in every one of the events that had been played out during the revolution. One of the allies of the new government was the French Army which managed to come out victorious in a series of battles against the royal armies of the Habsburgs. Its initial purpose to defend France had evolved into a war of territorial expansion into Austrian Netherlands and Prussia. However the enemies were more than the allies were. Firstly there was the continuation of the extremely cold winters which in their turn created failed crops, shortages in staple foods like bread and inflation. The value of money (Assignat) had dropped to eight percent of its original value. Then there were the Jacobins who had not really lost their influence on the poor people. In May 1795 they attempt the first revolt, they invade the National Convention at the Tuileries Palace but the army manages to restore order. Finally there were the Royalists and the Constitutional Monarchists that in October of that same year marched towards the Tuileries Palace with an army of 25.000. The Directory was saved by a young second rank General named Napoleon Bonaparte, a former Jacobine from the Island of Corsica, whose star shone enough that day as to catapult him in the first ranks of the French army in a matter of days.

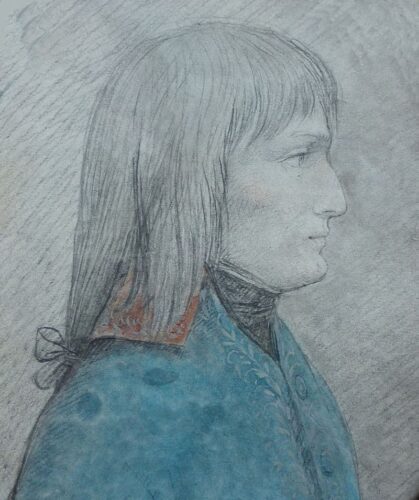

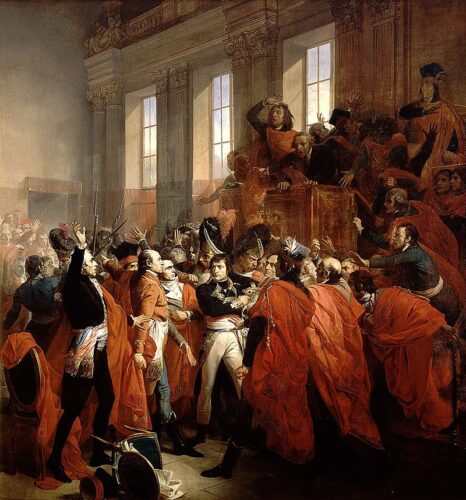

What Napoleon lacked in family name or noble credentials, he more than compensated with ambition, courage and military ingenuity. On March 2, 1796 Napoleon gets a new promotion as a commander in chief of the army of Italy. A week later he is married to Josephine of Beauharnais, a widow of the former General of the Army of the Rhine, six years older than him (Napoleon was 27 y. old at the time) with two children. Just two days after their marriage Napoleon leaves Paris for Italy. When he returned to Paris in 1799 after a series of military feats, the Second Coalition of European Monarchies, empowered with the participation of the Russian Empire had already launched its attack pn several fronts and Paris was ruled by the radical neo-Jacobins in a general climate of political intrigues and fiery factionalism. The people had grown tired of the Directory’s ineffectiveness and had substantial reasons to suspect the corruption of many of its members. On the other hand Napoleon’s popularity was not only a matter of one party or one class. He was equally admired by simple people and nobles, Jacobins and moderates. One month after his triumphant reception by the Parisians, on November 9, 1799, with the help of his brother Lucien Bonaparte, the much experienced Talleyrand, of Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (one of the architects of the French Revolution of 1789) and the minister of police Joseph Fouche, at the age of 33, Napoleon Bonaparte becomes the head of the state as first consul after a coup d’état that ended both the Directory and the ten year period of the French Revolution.

Just as Napoleon was putting his plan in force to put the capital back on its feet, his enemies were putting in motion their own, to get him out of the picture for good. In the first year alone Bonaparte managed to survive two plots against him, one in September 1800, at the premiere of a theater play and two months later, on Christmas Eve while on route to the opera, when the explosion of a trapped carriage barely missed him. Not only Napoleon remained unshakable but he became even more determined to make himself and his rule more powerful, to make Paris not just the most beautiful city in the world but the most beautiful city that ever existed.

From his new residence at the Tuileries Palace, Napoleon first reorganizes the capital into twelve districts, each governed by its own mayor, all under the umbrella of two Prefects appointed by him. He then orders the creation of new cemeteries outside the city and the building of three new bridges across the Seine. A new canal bringing clean fresh water from Ourcq river to Paris is dug out and a new committee responsible for its sanitation is established.

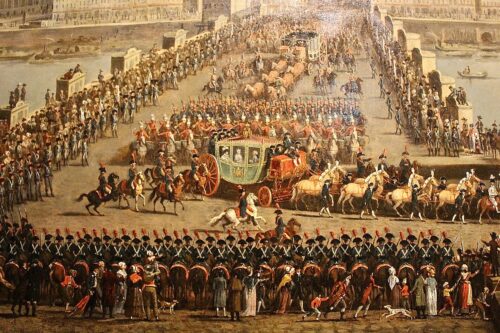

A national referendum in 1802 that made Napoleon First Consul for life and a second in 1804 that elected him Emperor of the French, both by an overwhelming majority, made him an omnipotent ruler. On 2 December 1804 Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned Emperor of the French at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris by Pope Pius VII and Josephine an Empress. Sumptuous luxury, regalia with a reference to the Roman Empire and Charlemagne, swords used for centuries by the Valois and the Bourbons, orchestras with four choruses, a 400-voice choir and over three hundred musicians, numerous military bands playing heroic marches, dazzled Parisians and made them feel that the greatest days were ahead. And for a period of time that was true especially for Paris.

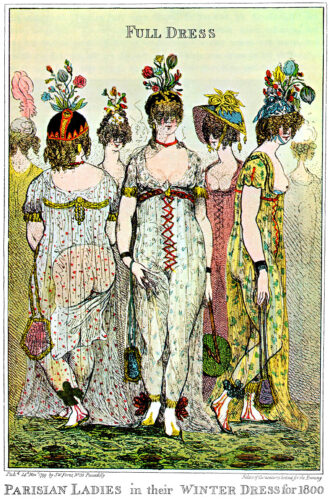

With protective tariffs and reliable financing, Napoleon encouraged the peasants to work efficiently and buy land, to produce more in order to support the economy and his growing army. Industry was also of interest to Napoleon. He visited factories, showed interest in processes and products, in the artisans and the managers. He aspired to bring science to the service of industry. He set up industrial exhibitions, organized the École des Arts et Métiers, and rewarded inventors and scientists. Inventions like the weaving apparatus distributed by the government in order for French textile industry to become competitive with the British. The Bourse (stock exchange) moves at its very own temple, the Palais Brongniart and the enormous Halle aux Vins intended to make Paris the main entrance port for wine in Northern Europe is established. Things in the economy started to look good and unemployment fell to a low point. The Parisians rejoiced and their joy was expressed through dancing, hundreds of bals publics sprang up and Guinguettes (a sort of suburb cabaret). Relations with the Church were restored and exiled nobles started coming back. Even the clothes that during the reign of terror were under the strict codes of political conviction, were now more extravagant, fashionable and lively than ever.

True to his goal, to turn his capital into a new Imperial Rome in 1806 Napoleon orders the construction of Arc de Triomphe and Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, inspired by the Imperial arches of Rome and the Vendôme Column, modeled by Trajan’s Column in Rome, made of the iron of cannon captured from the Russians and Austrians in 1805. Numerous new fountains including Fontaine du Palmier providing fresh water from the Ourcq River to the citizens of Paris were built around the city. Wide new streets like Rue de Rivoli and Rue de la Paix were inaugurated. The quays of the Seine were increased and reorganized while the Louvre became the Musée Napoléon displaying art treasures seized by the French Army. The Sorbonne that had been left in ruins by the revolutionaries due to its clerical orientation was reestablished based on the Faculty of Arts with people coming to study Greek, Latin, literary history, French literature, philosophy, ancient and modern history and geography.

The halcyon days of the Empire lasted until the end of 1809 but even during that period the economy struggled to keep up with Napoleon’s plans. The British superiority in the sea and the tightening blockade of the French naval trade had created dire repercussions in all sorts of businesses in Paris that relied on the precarious dealing of contraband to avoid shortages. The taxes were constantly on the rise but so was the deficit of the government. A bad harvest in 1811 was all it took for the grain prices to start spiraling upwards again and the ghost of famine to reappear. Napoleon was not the sweetheart of everyone any more. In fact outside the army that was always loyal to him there was little love for him in the streets of Paris in 1812. When the campaign to Moscow proved to be a disaster and people started to learn about its unprecedented extent, they were shocked to hear the Emperor was entertaining at the Tuileries. After the Russian debacle Napoleon would have to rely on the terror of his omnipresent secret police to keep order in the capital.

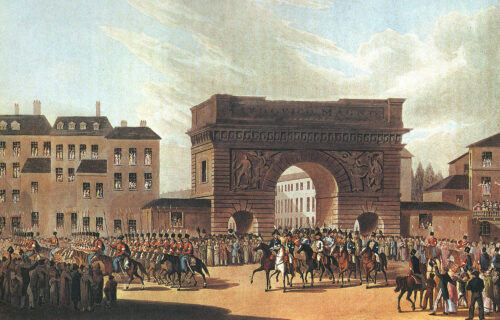

In the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, the largest battle in European history before World War I, Napoleon’s winning streak was shuttered by the joint army of Prussia, Austria and Russia. The dreams of a long lasting French Empire crumbled with a deafening roar on the backs of the thousands French soldiers lying dead on the battlefield. Napoleon retreaded and the allies marched straight to Paris. The Russian army entered the Porte Saint-Denis on 31 March 1814 with many Parisians waving white flags as a sign of good will, a clear indication of how tired they had grown of war during those years. Many observers like Napoleon’s architect Fontaine were taken by surprise by the people’s reaction and compared the event to a peaceful festival not a march of a foreign army. In April Napoleon signed his abdication and left Paris for Elba island.

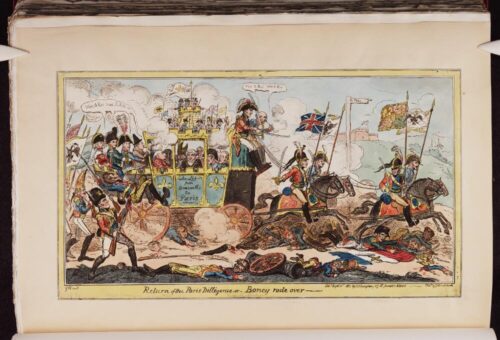

In May 1814, with the British, Russian, Prussian and Austrian troops still camped along the Champs Élysées, the exiled Bourbon Louis XVIII returns to Paris in an open carriage drawn by eight white horses. He was welcomed by exalted royalists and Napoleon’s former comrades, Talleyrand and Fouche who had orchestrated his return. In March of 1815 the King and the Parisians were awestruck to hear that Napoleon had escaped his prison and was on his way to Paris. Louis XVIII fled the city and Napoleon was back at the Tuileries Palace in less than a year from his supposed life-sentence. His fascinating escape captured the hearts of the simple people who could not stomach another royalist regime, the restored nobility and the dissection of their Empire. However when the possibility of an new war became a certainty, the enthusiasm resided. The Battle of Waterloo in June 1815 became Napoleon’s swan song. By mid July the allies had returned to Paris and in a matter of days Louis XVIII was restored to the throne. At last Parisians would have the peace they longed for after decades of war and revolution. Or at least that’s what they thought they would get.

In reality things were anything but calm. The period that followed is now known as the Second White Terror, a period when emigre extremists and ultra royalists finally took their revenge and settled old scores. Purging of the administration with thousands of public employees, soldiers and senior officers of the Grand Napoleon Army who were relieved of their duties, exiles, lynchings, trials and threats were all put in the service of the greater cause. Napoleon’s men and sympathizers had to be uprooted. The roots of a new revolution were thus planted from the very beginning. A fresh influx from the provinces increased the population to 714.000 by 1817 and the delayed industrial revolution arrived in the form of new manufacturing industries, gas lighting and daguerreotypes (first photographs). Infrastructure and the cityscape in general was left in the state it was during Napoleon by the Bourbons. Some iconic projects like the Burse were completed but sanitation and the sewer system was as primitive as ever. The situation worsened with the surging population especially in the poor neighborhoods where filth and rubbish were disposed on the streets and ran directly into the Seine when the rain would come. Money, good clothes and rich people were indeed more, due to the increase of commerce as it was always in times of peace but the poor people of Paris were always right around the corner, the markets were common for both rich and poor and the number of poor had been increased even more by the thousands of impoverished soldiers of the Napoleonic Army.

In the summer of 1830 with Charles X on the throne, a king strongly opposed to the concessions made by the crown in the past 40 years like the constitution that had been signed by the restored Louis XVIII in 1814, the economy was in a recession, the wages at a low point and unemployment on the rise. The icing on the cake was the soaring prices of grain and bread. When Charles X decided to suspend the constitution, reinstate the censorship of the press and tried to alter the composition of the elected Chamber of Deputies in July of 1830, it was only a matter of days before another perfect storm broke out. The July Revolution the one that inspired the famous Delacroix painting, was lit by the texts of contraband newspapers and journalists who cried for action against the Bourbons, action for the defense of the constitution. In a matter of only few days (July 27 – August 2) the last Bourbon king had been forced to abdicate and in a few days more he had departed from Paris with his son, the Dauphin, for Great Britain.