Early Adulthood

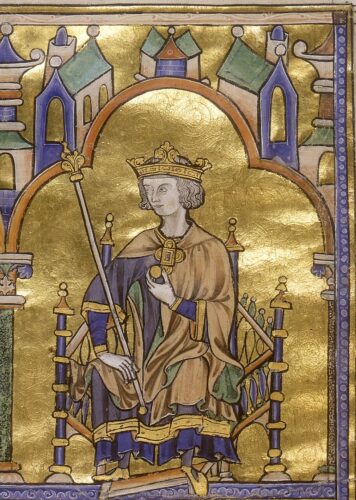

With its population growing rapidly (more than 150.000 in 1250) and the kings that followed cashing in on Philip Augustus’ success, Paris seemed mightier than ever. Based on the model of the strong authoritarian monarch his heirs consolidated the fundamental administrative institutions to further serve the crown, not to control it. Louis IX came to power not long after Philip II’s death in 1226. The young of his age (only 12 years when he became a king) and his phenomenal religious zeal made him stand out right from the start. Louis IX squandered a great amount of the royal coffers in two disastrous crusading expeditions against the Muslims but nevertheless managed to keep his finances healthy throughout his long reign. He even lifted many of the tax burdens imposed by his predecessors thus helping create a new prosperous middle class the likes Paris had never known till then. In 1240 Louis spent a fortune in order to put Paris at the forefront of Christendom with the acquisition of what was believed to be the Crown of Thorns from Emperor Baldwin II of the Latin Empire of Constantinople. In less than 10 years he would leave his architectural mark on Paris with the Gothic masterpiece of Sainte-Chapelle created within the Palais de la Cité, in order to house the earth-shaking relic.

The intellectual life of the city entered into a phase of significant proliferation especially in the field of philosophy based on the growing number of gifted scholars like Saint Bonaventure (studied in 1243 and later became a master in the university of Paris), Thomas Aquinas (studied at the university of Paris after 1245 and later became a master), Saint Albert Magnus (teacher at the University after 1245) and Roger Bacon (teacher at the university in the 1240’s) . These intellectuals, philosophers and early scientists reshaped the medieval school of theology based on the freedom given to them by the university of Paris and the prism of Aristotelian thought infused to them by the works of the ancient Greek philosopher, who had just recently been translated in Latin in his entirety.

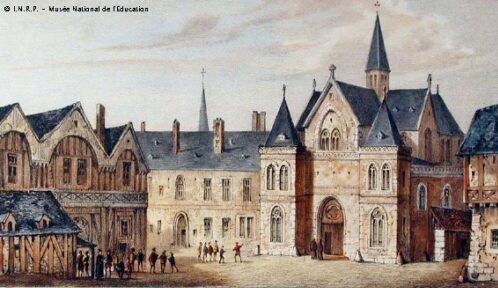

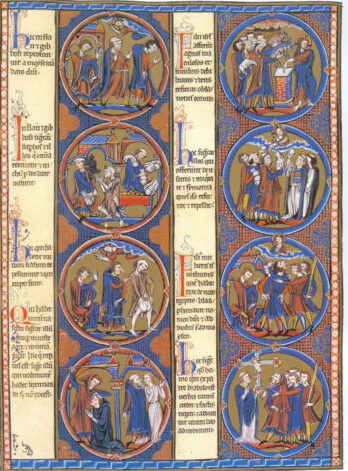

The studious atmosphere that permeated medieval Paris was imprinted in the most graphic and elaborate way on the numerous volumes of illuminated manuscripts produced not only within the city’s monasteries as was the norm until then but also in lay workshops employing an increasing number of artisans who served the clergy, the schools’ masters and the nobility, as well as the mercantile and professional classes. The distinctive style of this Paris school of scriptoria was later copied throughout France. In 1257 Robert de Sorbon, Louis IX‘s confessor, established a college within the university that would become famous enough as to rename the whole institution as the Sorbonne. Accommodating rich and poor, irrespective of family or geographical background and using criteria of intellectual excellence, the Collège de Sorbon soon made a name for itself as an elite, meritocratic school. By the end of the Middle Ages, the University of Paris had become the biggest cultural and scientific center in Europe, attracting some 20,000 students every year.

Louis IX’s Christian outlook was soon extended to the field of state politics where despite the fact that he ruled the most prosperous and largest realm in Western Europe he actively sought and achieved peace with the English. His position of strength did not prevent him from making territorial concessions in the southwest (Gascony and Guienne) with the Treaty of Paris in 1259. The king’s piety and eagerness to follow the Papal instructions would create a long lasting precedent of mutual support and intimate relationship between the French kings and the papacy that would only cease with the Italian unification in the 19th century. It would also make Louis IX the only canonized king of France despite his many misdeeds in the eyes of modern day seculars like the introduction of the inquisition in France, the bloody expulsion of the Cathars, the massive burning of Jewish religious books in Paris and of course the fervor for crusades. St Louis is venerated by Roman Catholic Church and Anglican Communion and celebrated every August 25.

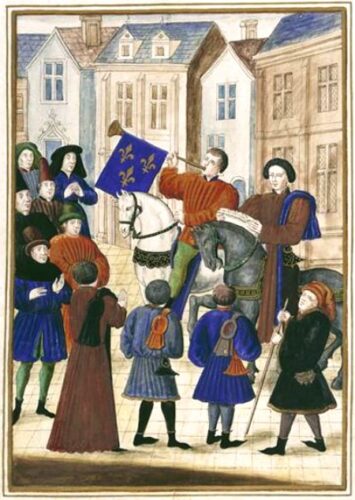

At the time it seemed everyone in Paris wore a gown or a uniform. There were the student gowns and the gowns worn by the masters of the university. There were the gowns and uniforms worn by the members of the royal court, the nobles and the members of the administration. Then there were the soldiers and members of the guet, of the police guard patrolling the streets. And of course there were the members of the church, of the mushrooming monasteries and abbeys and those of the monastic orders.

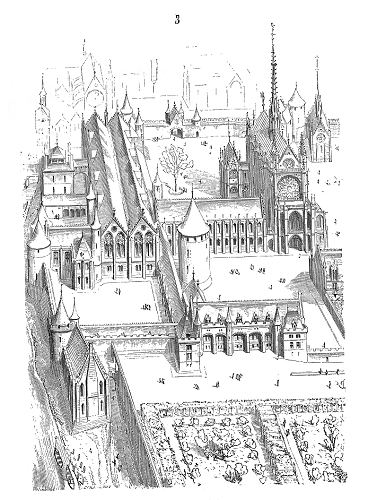

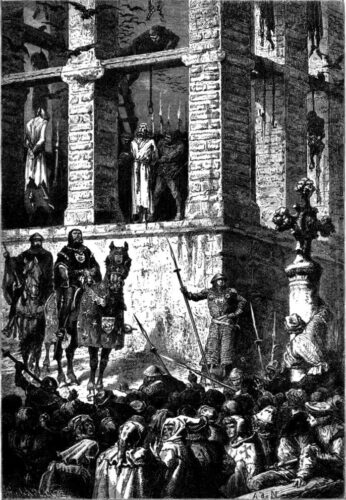

From the beginning of the 13th century until the end of St. Louis reign in 1270, the Dominican Order, the Franciscans, the Augustinians, the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar had all come to Paris. The Knight Templar in particular had grown so strong and prosperous that after 1240, they had their own, very impressive castle in Paris, the Temple Tour. The Temple Tour was an intimidating 5 stories and 55 meters high tower that served as the treasury for King Louis IX, Philip III, and Philip IV. The tower was located near the Place de Greve, a former marshland, drained by the Templars before the construction of their tower. In the shadow of the tower were several other Templar houses, a farm, a hospital a church and a cemetery. There was also the residence of the master of France that became the residence of the Master of the Order after the conquest of the city of Acre in 1291 by the Mamluks.

At the end of the 13th century the French throne was occupied by a ruthless and money-hungry king. Philip IV later known as the Iron King (r. 1284 – 1314) had great plans for himself and his kingdom. He dreamt of a new Christian Empire that would be controlled from Paris and would spread from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. According to his plan the Papal state would be under the complete control of the most powerful king in Europe. This grand plan had of course some practical complications. One of them was the great need for resources.

The problems started when the Iron King put forth his plan for the reconstruction of the Palais de la Cite in 1298. His dream for a new sumptuous palace of exceptional beauty required lots of money. The annulment of the crown’s debts, the new taxes imposed on businesses and income, the reduction of pure gold contained in the state currency, the relentless confiscations of private properties just didn’t cut it. The Lombards and the Jews who initially served as the king’s lenders had already been expelled from Paris, their properties confiscated, the royal obligations cancelled. There was only one player left and the king had his eyes on their mythical fortune. Stepping on the envy of the common people, the widespread reputation for the Templars’ greed but most of all on the total control over the new Pope (Clement V was the Pope who moved the Papal throne from Rome to Avignon, a mere pawn of the French king), the Iron King declared war on the Templars.

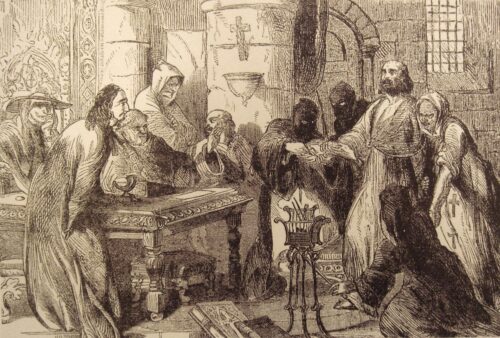

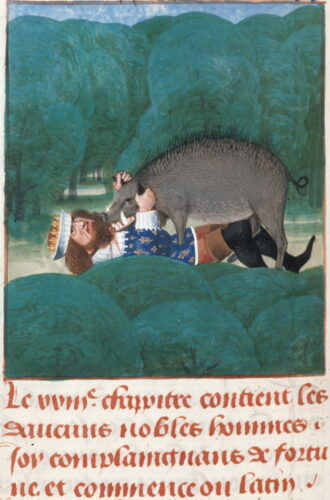

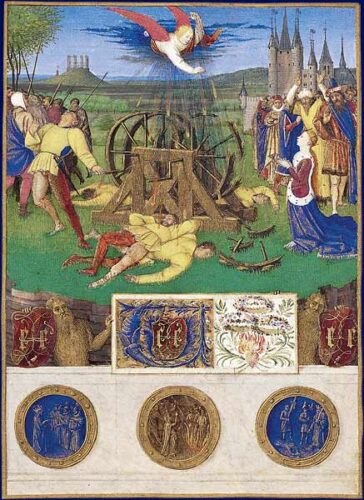

All sorts of horrible accusations, heresy, necromancy, sodomy, usury and fraud became the stunning pretext behind a well organized operation of massive arrests on Friday, 13 October 1307, of hundreds of Knights Templar among them the master of the order Jacques de Molay. After many lengthy trials and horrific tortures that led to the early deaths of nearly forty knights, Paris would experience one of the most gruesome spectacles in its history, with the burning of 138 Templars at the stake, according to the favored ritual of the inquisition. The climax came in 1314 with the burning of Jacques de Molay and three more masters of the order on a small island in the Seine, the Ile des Juifs, near the palace garden. To this day the date of Friday the 13th is considered to be an ominous one in the whole western world.

The first public riots of merchants and simple people struck by the economic policies, the rising rents and the rampant inflation of the early 14th century had been addressed with equal ferocity by the Iron King who hanged twenty eight of the offenders at the four entries of Paris. He would have no more revolts until the end of his reign in 1314.

Paris was by then the most populous city in Europe with more than 200.000 people within its walls, the kingdom of France the strongest and most populous in Europe. Philip IV however would be mostly remembered for his cruelty. The Templars’ curse (according to the tradition Jacques de Molay uttered a terrible curse at the time of his death against the king and his future heirs) would be followed by many years of famine, plagues and deaths of three different kings, all Philip’s sons, all without a male heir. The Capetian dynasty was thus over after three centuries.

More and more people flocked to the capital from the country, seeking jobs and food every time the crops failed to sustain them. The walls that back in the time of Philip II seemed like an extra large costume, now barely fit every house in. With most people being poor in a crowded city without street lighting and the dominant figure of the iron king out of the picture, crime took off. The wooden gallows on the hill of Montfaucon had to be rebuilt in stone in order to withstand the load of extra weight. Sanitation was also non existent. The Seine worked as a large open sewer polluted by human waste, waste from butchers, tanners and other clothing manufacturers. The narrow medieval streets were overwhelmed by the smells of urine (the chamber pots were routinely emptied out of windows onto the street), of unwashed people and flocks of sheep, pigs, and cows being driven to the markets where the smells mus have been overwhelming. Street merchants went door to door selling fish, garlic, onions, chickens and all sorts of other odorous products. The malodor of Parisian streets became notorious.

Just when France was entering the bloodiest first round of the Hundred Years’ War with the English, three years after the completion of Notre-Dame (1345), the Black Death came to Paris. The plague found an ideal playing ground in the unhygienic time bomb that was Paris at the time. For two years, the lucky ones that managed to survive the pandemic lived in a state of fear for themselves and their loved ones. The death rate reached 800 a day, the rich people and the king left the city in panic and medieval superstition found its culprit in cats.

Meanwhile France had already lost two important battles to the English, the Battle of Crécy in 1346 where superior English arms crushed a superior in numbers French army and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, where Edward of Woodstock not only devastated the French army in what was more a massacre than a battle but he even managed to capture the French king, Jean II, his brother Philippe and many of his nobles.

The two shattering defeats had discredited the Valois in the eyes of the people. With Jean II being captive of the English king, his son Charles V, took over the regency. His young age (18 y. old) and the fact that unlike his father and brother, he had left the battlefield of Poitiers made it harder for him to keep a respected royal profile especially during a period when the rising middle class of merchants and craftsmen questioned the whole status quo and looked for a more democratic way of government.

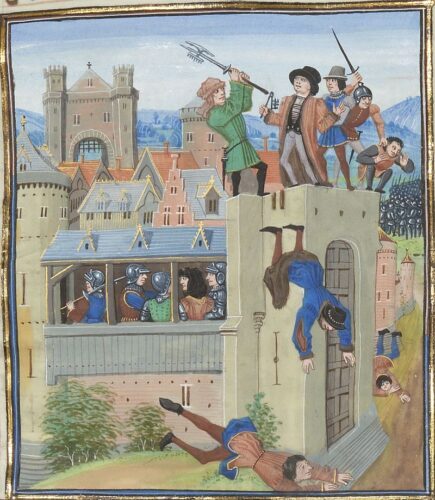

Étienne Marcel was the provost of the merchants of Paris. When the young king tried to raise new taxes in order to pay for the ransom and cover the excessive expenses of the war, a war so destructive for the interests of merchants, Marcel made his move. With an aim to bridle royal authority with democratic institutions, Marcel led a band of armed Parisians and invaded the Palais de la Cité on February 22, 1358. Two of the king’s marshals were killed before the eyes of Charles V who fled Paris in order to regroup.

Another army of 5,000 peasants suffering from the deprivations of war joined forces with Marcel in May, who was also joined by King Charles II of Navarre who was on the head of an army of English mercenaries. The people of Paris were however divided and riots broke out, forcing Charles of Navarre to flee the city. When Marcel tried to open the gates of the city to the mercenaries of Charles of Navarre for a second time, he was killed at the bastion of Saint-Antoine. Most of his leading supporters followed the same fate. Charles V re-entered his capital on August 2 1358 triumphantly.

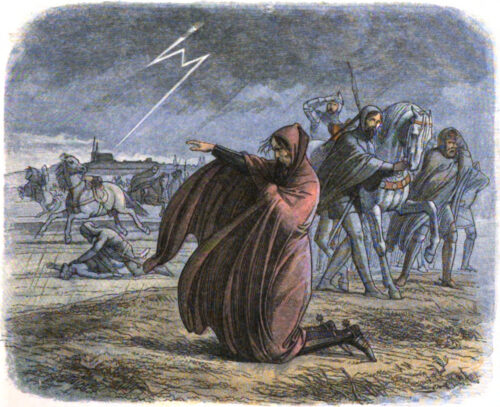

In March 1359 the captive King Jean II signs a treaty with the English in his effort to hold on to the throne. The treaty ceded most of Western France to the English and imposed a unbearable ransom of million écus to the French. Although the English had the upper hand Charles V decided not to give in, overriding the orders of his captured father. The dauphin (name given to the eldest sons of the kings of France) knew the English were superior in an open field so he avoided pitched battles. In the Spring of 1360 King Edward III of England reached Paris. Looking for a big battle that would secure him the French crown, Edward followed a strategy of scorched earth, burning everything that stood outside the walls of the city. Charles V had already started rebuilding and reinforcing the walls and moats of the city since 1356 and the English were not actually prepared for a long siege, so after a few insignificant skirmishes Edward left Paris, plundering the surrounding countryside and heading to Chartres instead. On the 13th of April 1360, the day of Easter Monday, the English army is hit by a huge storm that kills more than 1000 soldiers outside the walls of Chartres. Black Monday was interpreted by both sides as a wrath of god. Edward was forced to accept a treaty with much less gains than it was expected at the start of the expedition and most importantly one that repudiated his claim on the French throne.

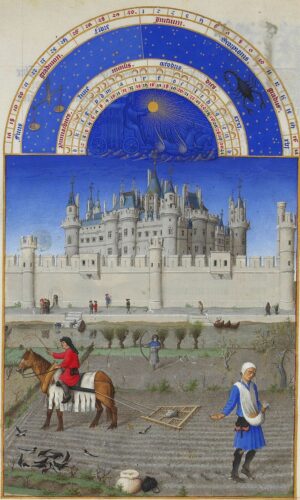

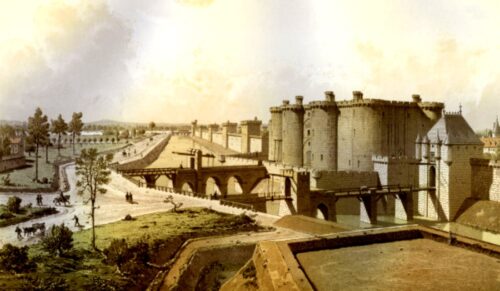

The civil war was over and the English had been temporarily appeased but the widespread poverty was now more evident than ever, with the streets of Paris being full of wandering beggars. Plague came back in 1360 reaping the lives of Parisians for three years in a row. Charles was forced to leave Palais de la Cité for the Castle of the Louvre that was turned into a proper royal palace with ornate rooftops, carved windows, spiral staircases, and a grand garden. He was the first French king to use the Louvre as his palace. In the same time his new wall embraced all the recently built suburbs that reached all the way to the Abbey of St. Germain on the right bank. Six main gates gave access to the interior of the city. One of them was the Porte Saint-Antoine that would be protected by the new fortress of the Bastille. The foundation stone of the new castle was laid in 1370 but Charles V wouldn’t live to see it finished. His son Charles VI completed the construction of the fortress after the death of his father in 1380.

At the end of Charles V‘s reign the French had started their counter attack against the English and this time the tide had turned. When Charles V died however in 1380 that momentum was lost. Charles VI was eleven years old at the time so the government was entrusted to his four uncles, the Dukes of Burgundy, Berry, Anjou, and Bourbon who squandered the royal funds for their own personal profit and kept raising taxes. With Parisians exhausted by the constant recurrence of plague epidemics (one every three years avg), the war and the high taxes, a new revolt in Paris had to be put down with force in 1382. When Charles VI finally dismissed his uncles and assumed his role in 1388 the people rejoiced hoping for better days. Their hopes were shuttered when the new king suddenly showed increasing signs of madness in 1392 causing a new round of civil unrest at the beginning of the new century.

When Charles VI was officially declared unfit to rule in 1393, a feud started between his younger brother Louis I, Duke of Orleans and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (one of the uncles) who had assumed the role of the regent, sidelining the young prince. Louis resented his uncle but was in essence trapped by a superior strategist. When Philip the Bold died in 1404, his son John the Fearless was in charge of the royal council. Despite his short-hand at that point Louis was the king’s brother not the cousin, so in April of 1407 he finally managed to reshape the composition of the royal council and set himself in charge. The Duke of Burgundy (John the Fearless) was not willing to let royal power slip through his fingers so in November of 1407 Louis I of Orleans is assassinated by a group of masked criminals led by a servant of Duke of Burgundy on Rue Vieille du Temple (in front of today’s Amelot de Bisseuil Hotel). All the people in Paris knew about the feud and most had already sided with the Duke of Burgundy so John the Fearless didn’t bother to mask his involvement. Soon however, the capital found itself divided into two hostile parties. The Orleans party, also known as the Armagnacs, led mostly by members of the royal administration and treasury, whereas supporters of the duke of Burgundy were simple people, students of the University and members of the guilds who blamed old administrations for their high taxes.

John was not only fearless. He was also a cunning man. He soon managed to win back Charles VI‘s favor and secure a royal absolution for his crime. He then orchestrated the Cabochien revolt in the Spring of 1413, in essence a pogrom against the Armagnacs that very soon turned into an uncontrollable chaos, where wealthy Parisians were assassinated or abducted for ransom. The merchants took the situation in their hands by recruiting their own soldiers who took back control and ousted the leaders of the revolt, the Burgundians and John the Fearless from Paris. Although both parties had secretly conspired with the English in their effort to prevail, when King Henry V of England invaded French territory and asked for their support in his claim to be the rightful King of France, both parties refused to bend the knee. When the time of the big battle came however in 1415, John the Fearless did not send his troops. In the Battle of Agincourt as many as 10.000 French warriors fell to Henry V’s long-bowmen. Most of them from the party of the Armagnac. Within ten days of the battle, the Burgundians had mustered their army and were marching for Paris. The city didn’t fall until May 1418, when John’s allies from inside the city opened the Gate of Saint Germain to the Burgundian army. Hundreds of Parisians fell to the swords of the Burgundians but not the Dauphin, Charles VII of France who managed to escape unharmed. The nemesis for all the offences committed by John the Fearless came in September of 1419 when he was murdered by the Armagnac during what he thought was a diplomatic meeting with the Dauphin Charles VII.

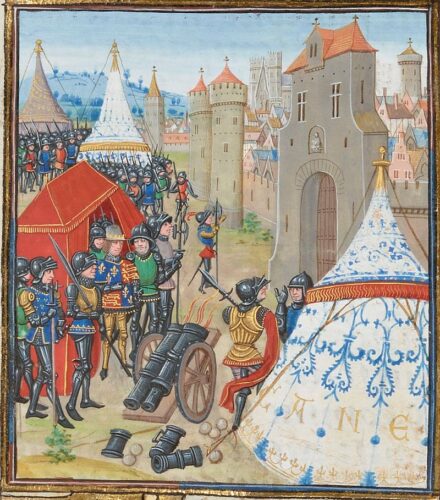

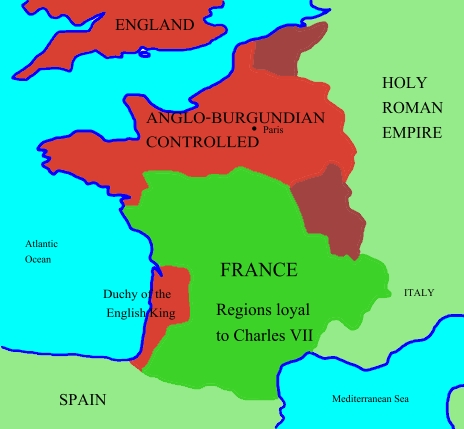

At the time of the death of his father in 1420, Charles VII had officially lost the north of the country to the English and Paris remained under the control of their Burgundian allies. Although the French people regarded him as the rightful king, the English derisively referred to him as the King of Bourges, after the town where he had set his court in central France. The Parisian merchants and the board of the university had to take an oath to respect the English rule, Charles VII was found guilty of treason, all his privileges to land and titles were invalidated by a Parisian court and a small English garrison was settled in the Bastille and the Louvre. The administration of the city was left to the Burgundians. The course of the war suddenly took a different turn with the arrival of Joan of Arc in 1429 but her winning streak was broken under the walls of Paris by the arrows and crossbow bolts fired by English, Burgundians and Parisian soldiers. The latter had feared that the Armagnac would slaughter everyone if they took back the city. The siege nearly cost Joan’s life which would be eventually taken a few months later (May 1431) after her capture by the Burgundians at Compiègne.

The English held Paris until 1436. Α year earlier Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, had signed the Treaty of Arras, by which the Burgundian faction rejected their English alliance and became reconciled with Charles VII. For Paris to be taken Charles had to go into secret negotiations with the Parisian bourgeoisie and promise a total amnesty. The Treaty of Arras was also the official end of the civil war between the Armagnac and Burgundians. After nineteen years of foreign occupation, Charles VII entered Paris, on November 12, 1437. In the twenty years that followed he managed to reconquer all the territories occupied by the English with the exception of the northern port of Calais. He would forever be remembered as Charles the Victorious.