Grown Up

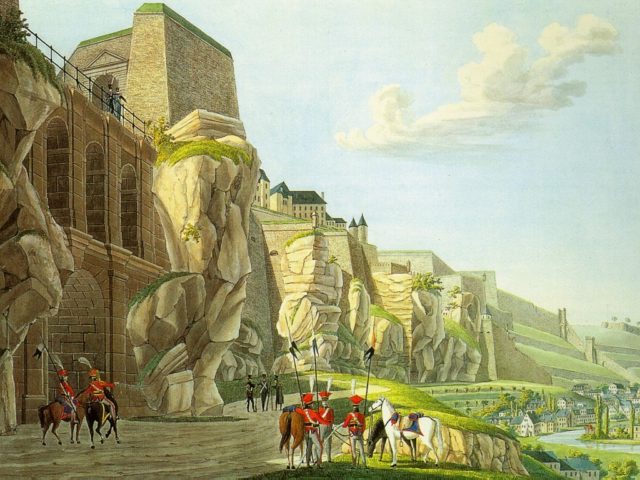

Vauban, one of the most competent fortification engineers in history (between 1667 and 1707 he upgraded the fortifications of around 300 cities & built 37 new, of which 12 belong in the UNESCO World Heritage list of monumental fortifications today) immediately started a massive re-building and expansion project emphasizing in the already existing web of underground tunnels and system of case-mates which he extended even further. It was during that time that Luxembourg acquired the nickname “Gibraltar of the North”.

Louis XIV’s aggressive policy would not go on unanswered. In 1686 the alarmed French neighbors would form The Grand Alliance that would lead to the Nine Years’ War and finally the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 which forced France to return Luxembourg to the Habsburgs.

Four years later, at the outbreak of the sequel war between the two sides known as the War of the Spanish succession, the French would return to Luxembourg where they stayed for more than a decade (1701-1713), during which there was a considerable conflict in the area between them & their faithful allies the Bavarians on one hand and the Grand Alliance of the Holy Roman Empire, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic and Portugal among others, on the other.

After 1713 the treaties of Utrecht & Rastatt stated that the Spanish Netherlands (Belgium and Luxembourg) would pass from the Spanish to the Austrian Habsburgs who would remain in the country until the end of the 18th century.

The fortress of Luxembourg would now be one of the main strategic pillars in the defense of the Austrian Netherlands against any attempt a French expansion. That was the reason behind the extensive expansions of the casemate system that took place after 1737 at the Bock.

By significantly enlarging the already existing complex the Austrians managed to construct an extraordinary underground maze that would reach 40m (130ft) in depth & 23km (14ml) in length with enough space to fit a garrison of 1200 men, housing equipment & horses, workshops, kitchens, bakeries & slaughterhouses.

The narrow openings for artillery carved into the Bock along with the structure on top of the rock could now accommodate the firepower of more than 50 cannons. At the same time, the building of several exterior forts like Fort Thüngen created a triple line of defenses on all sides that would make the Bock impregnable.

The Austrian fears of a French attack brought an exponential increase of the troops that were stationed in the fortress, reaching 10.000 soldiers between 1727 and 1732, while the civilian population of the city did not exceed 8,000. In 1787 the citizens of Luxembourg stated in a petition that they had “the sad privilege of living in a fortress, a privilege that is inseparable from the lodging of soldiers”, a problem that tormented its inhabitants, especially those (usually of lower social status) who were assigned with the obligation of housing a soldier but received no compensation from the Austrians or the Spaniards before them.

The new defenses were finally put to a test in 1794, five years after the French Revolution and two after the declaration of war by Revolutionary France on the Habsburg monarchy. The French Revolutionary army laid a siege on the city that lasted more than seven months. The city surrendered only due to the lack of supplies, confirming the titles of “the best fortress in the world, except Gibraltar” and “Gibraltar of the north”.

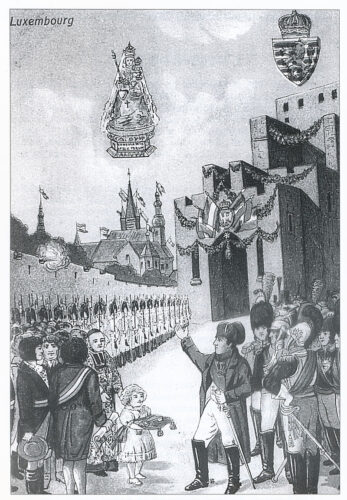

The capture of the fortress allowed the French Republic’s annexation of the Austrian Netherlands with the biggest part of the country of Luxembourg becoming part of the Département des Forêts (department of the forests, from the neighboring Ardennes forests) of the First French Republic in 1795.

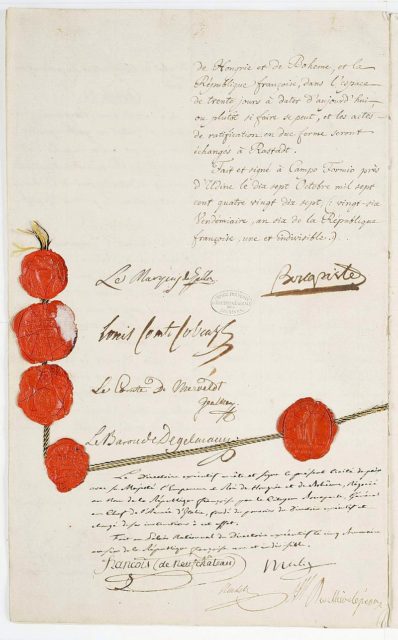

The constitution of Revolutionary France and a modern state bureaucracy were introduced as soon as the annexation became official with the Treaty of Campio Formio between Napoleon Bonaparte as representative of Revolutionary France & the Austrian monarchy in 1797.

The introduction of compulsory military service for all French subjects between the age of 20 and 25 triggered a rebellion known as Klëppelkrich or the Peasants War in the late September of 1798.

The rebellion wasn’t as popular in the middle classes (hence its name) for whom the spirit of anti-clericalism & modernization of the French Revolution was especially inspiring. As a result it was easily put down by the occupiers. As a département of Napoleon’s Empire Luxembourg was controlled by a central commissioner of French origin throughout the four restructures of the Napoleonic Empire.

Under the Napoleonic umbrella, all the administrative, institutional, economic, social & political institutions of Luxembourg were discarded without restraint while religious persecutions and the suppression of the religious orders generated even more discontent.

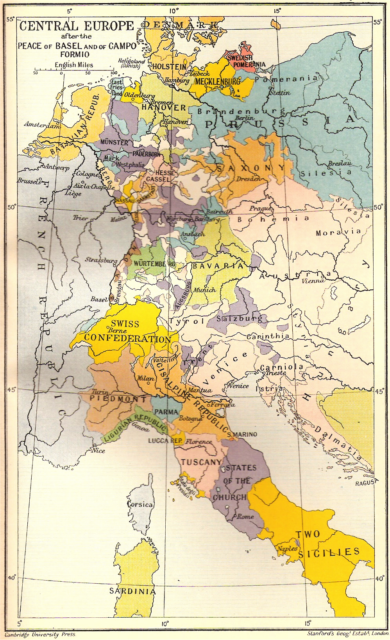

The Napoleonic Empire crumbled after 1814. The French were forced to leave Luxembourg to the allies (Prussia, Austria, and the Netherlands) who established a provisional administration and moved the final status to be determined at the Congress of Vienna the following year.

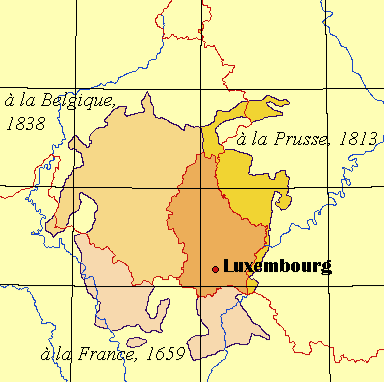

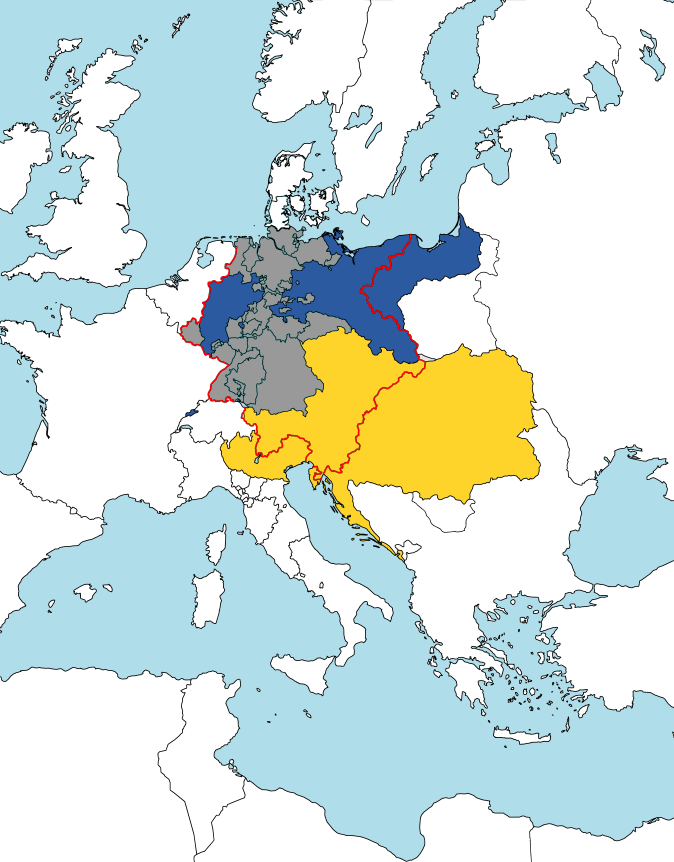

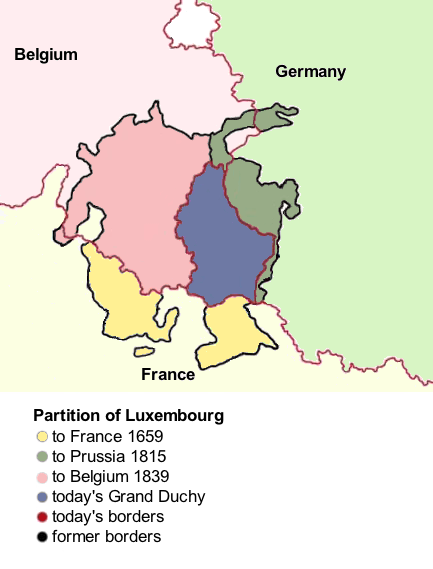

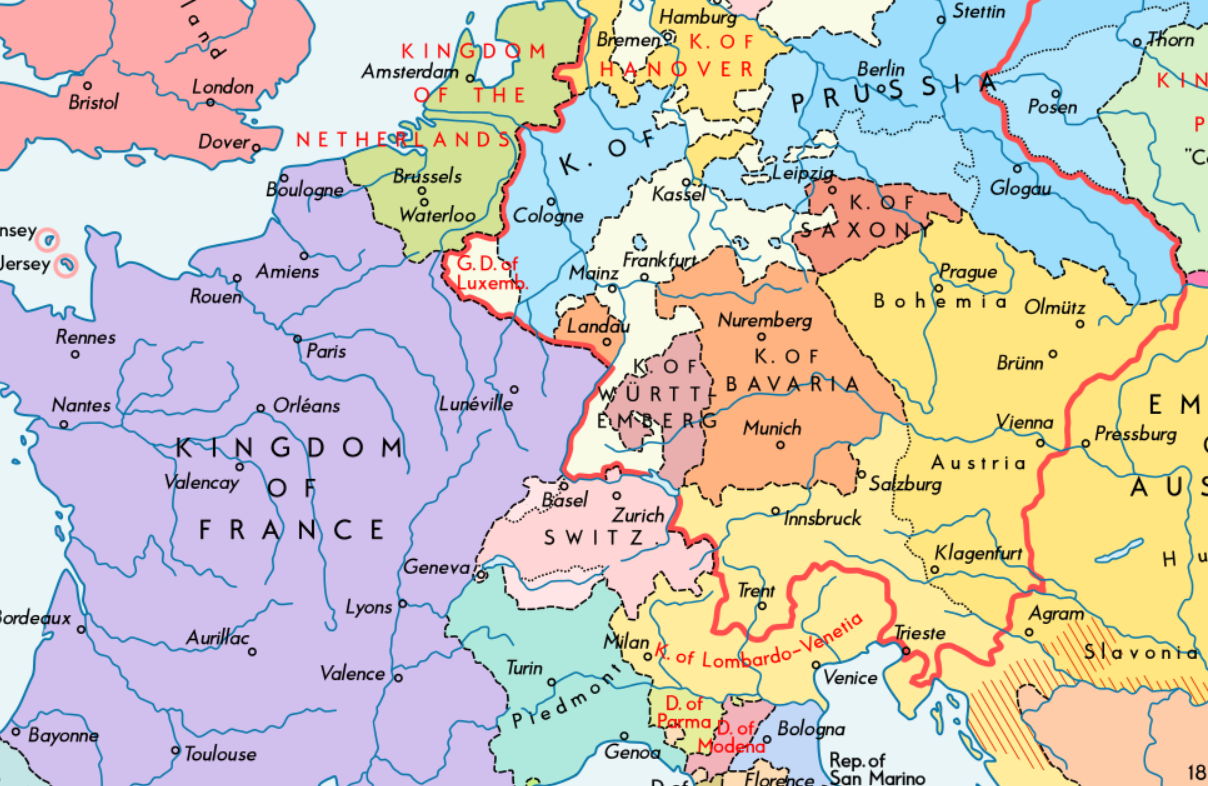

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 raised Luxembourg to the status of a Grand Duchy, in essence, a sovereign state with the eastern parts of the country going to Prussia (now Germany) and at the same time complicated things even more by placing the country within the German Confederation while appointing King William I of Netherlands (1772-1843) as its ruler.

As a result, Prussia received the right to appoint the fortress governor and the garrison would be made up of 1/4 Dutch troops and 3/4 Prussian troops. King William, I treated the former Austrian Netherlands as a conquered country and taxed it heavily when at the same time he tried to impose a linguistic reform after 1823 which intended to make Dutch the official language. The upper & middle class in Luxembourg however was mostly French-speaking.

Religious differences between the south and north became the straw that broke the camel’s back with much of the population of Luxembourg joining the Belgian revolution in 1830 against the Dutch rule. Except for the fortress and the main parts of the city of Luxembourg which were still held by Prussian-Dutch troops and were considered loyal to the Dutch King, the rest of the country was under the control of the new Belgian state from 1830 to 1839. William, I wasn’t willing to step aside peacefully.

The dispute was resolved by the Great Powers (France, Netherlands, Russia, United Kingdom, German Confederation) and the Treaty of London in 1839 which recognized the independence of Belgium splitting in the same time the territories of Luxembourg in half (3rd Partition) with the western Walloon (French speaking) part going to Belgium, while the rest (including the city of Luxembourg) remained under King William I’s control in the same status as before (autonomous Grand Duchy in the German Confederation, in essence, controlled by the Prussians).

The loss of such a great part of its region caused major economic problems for the state of Luxembourg which still relied on agriculture to a great extent. As a counter-measure, King William II of Netherlands (r. 1840 to 1849) introduces Luxembourg to the German Customs Union (Zollverein/ the first economic union without a simultaneous political union in history), a measure which proved to be insufficient judging from the large number of people who left Luxembourg during that same period.