Baby

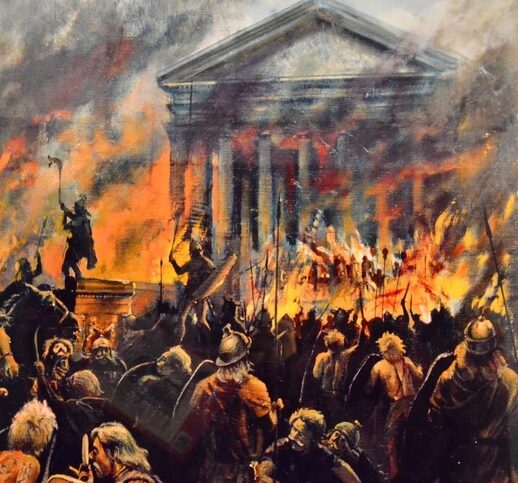

Londinium’s promising headway was disrupted in 60 AD by Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni tribe, who was chosen by her tribe & the tribe of the Trinovantes to lead the revolt against the Romans after her husband’s death and the attempt of the Romans to annex his territories in their new Roman Province.

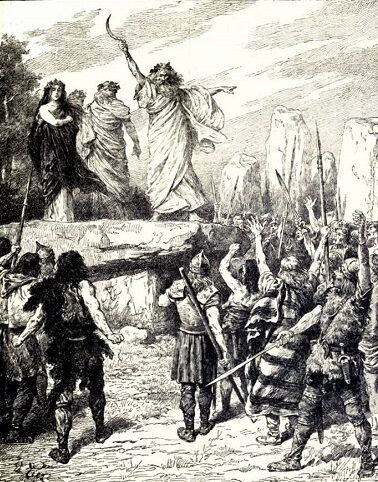

With the Roman army and Governor Suetonius Paulinus busy campaigning against the Druids in North Wales, the timing couldn’t be more perfect for the rebels who razed the whole city to the ground, killing anyone who had not abandoned it. Boudicca’s fire left a thick burnt layer of red ash in the soil still discernible today in archaeological excavations around London.

It didn’t take long for the mighty Roman war machine to regain control of the island and for the destroyed town to be rebuilt, this time as a well-planned and walled Roman city. The Imperial Procurator (a financial equivalent of a governor) of the Roman Province of Britain named Gaius Julius Classicianus was the one who rebuilt the city after the fire. He lived and died in Londinium. Parts of his monumental tombstone have been dug-up and are on display in the British Museum today.

Its vantage point made Londinium’s re-building a more or less obligatory task for the Romans. By the late 1st, and early 2nd century AD a booming Roman city, with a forum (marketplace) – much bigger than today’s Trafalgar Square– and a basilica complex (law courts, assembly hall, treasury & residencies of the city administrators) occupied nearly 2 hectares of land and stood three stories high.

The forum was considered to be the largest north of the Alps. Along with the temples to Diana (St. Paul’s Cathedral today) & the god of Mithras found at Walbrook River, the public baths and the wooden amphitheater on the north-western outskirts of the city, all stood as witnesses of the significance the Romans gave to the re-established Roman city.

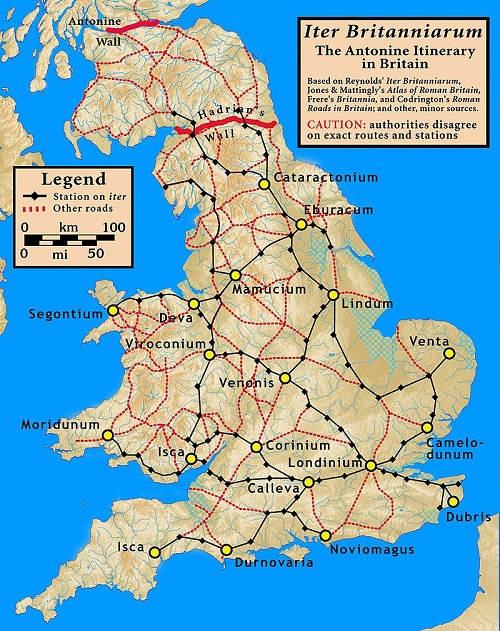

Ships with wine and pottery from Gaul and Italy. Olive oil from Spain and marble from Greece. Boats packed with export goods such as copper, tin, silver, oysters, and wool, roamed the deep waters of the city’s port. The increasing volume of Londinium’s naval trade increased the importance of the Roman town which replaced Camulodunum (the Capital city of the Trinovantes and the Catuvellauni after them) as the capital city of Roman Britannia by the year 150 AD.

By the year 200 AD Londinium had a hiking population of over 45.000 people, an elaborate governor’s palace (beneath Cannon St. Station today), and a military fort, home of the Roman garrison. The fort was located near the city’s large amphitheater which had been rebuilt in stone after the fire. A defensive wall of 6 meters high & 2.5 meters thick defined the city’s shape & size for the centuries to come (today the Roman walls would encircle the famous financial district known as the City).

In the context of the civil wars that had erupted within the Empire after Commodus’s death in 192 AD, Emperor Septimius Severus tried to solve the problem of powerful governors in Britannia that could prove to be a threat by dividing the province into Britannia Inferior to the north, with its capital at Eboracum (modern York) & Britannia Superior with its capital at Londinium.

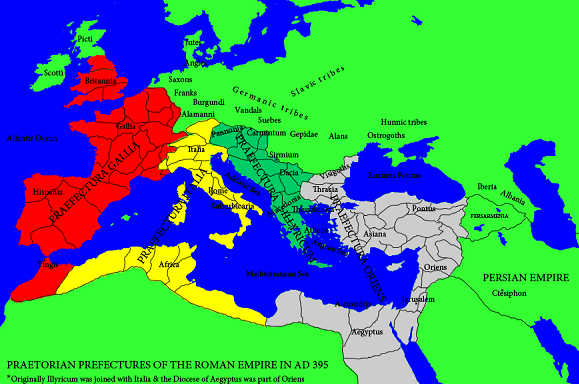

Britannia & its capitals had managed to stay unaffected by the gradual demise of the empire’s cohesion aside from the economic distress until in 260 AD the island was swirled into the internal tensions caused by Imperial pretenders. First, the island became a part of the Gallic Empire of the revolted Roman general Marcus Postumus until Emperor Aurelian reunited the Empire in 274 AD. Then in the late 270s, Londinium became the stronghold of two revolted Briton usurpers, who were defeated by Vandal & Burgundian mercenaries sent by Emperor Marcus Probus.

In 286 AD a naval commander of the Roman fleet in the English Channel named Carausius set himself up as an emperor in Britain and Northern Gaul and minted his coins from Londinium which held on to its role as the commercial and naval center of the island. Carausius managed to stay in power until 293 AD when he was murdered by his treasurer Allectus. Allectus succeeded him for a short period during which he even issued his coins until he was finally defeated by the armies of Emperor Constantius Chlorus who arrived in London to celebrate his army’s victory in 296 AD.

Constantius stayed in Britannia and Londinium for a few more months saving the city from an attack of Frankish mercenaries, former allies of Allectus who were now roaming the province without a paymaster. After eliminating the threat, Constantius replaced most of Allectus’ officers and subdivided the island into four new provinces. Londinium became the capital city of Maxima Caesariensis.

Christianity had arrived in the British Isles already in the 1st and 2nd century AD. Londinium acquired a Christian bishop from the very early days of Christianity the oldest recorded name being that of Restitutus who attended the Council of Arles in 314.

Another Roman civil war at the beginning of 350 AD had left the imperial military force on the island weakened and depleted leading to the devastation of 367 AD, known as barbaric conspiration. Picts from Caledonia (Scotland today), Scotti from Hibernia (Ireland today), and Saxons from Germania managed to overwhelm nearly all the Roman outposts, sacked Londinium and the rest of the Roman cities, and killed many of their civilians.

A year later (368 AD), Count Theodosius, sent by Emperor Valentinian I (364 to 375 AD), managed to re-conquer Londinium which became the headquarters of his successful campaigns against the invaders. Although the Romans ended much of the chaos, the raids and the revolts were far from over.

In 383 AD Magnus Maximus, a distinguished general in Count Theodosius’ army and military commander in Britain for 3 years is proclaimed emperor by his troops. He begins his campaigns on the continent taking much of the Roman army stationed in Britain with him. During that rebellion, London produces its last Roman coins in history.