Adolescence

The conflicts between the different factions within the Italian cities of the time had forced Pope Innocent III to take the matter into his hands and change the form of the civic government, from consuls to a single senator or Podesta, who, directly or indirectly, was appointed by the pope. Despite the short-lived alliance of Siena with the Papal camp through the Tuscan League, the city was governed by the Ghibelline faction (side of the Emperor).

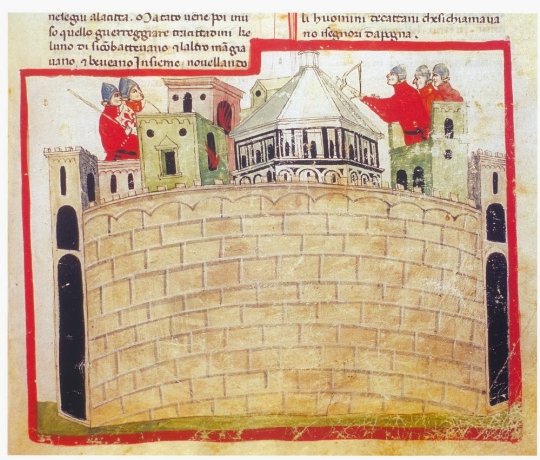

In 1208 the town of Montepulciano was under siege by the Sienese. The Florentine Podesta decided to run to Montepulciano’s aid and in June of that year, the two armies met at Montalto. In the fierce battle that followed both sides suffered heavy losses but the Florentines prevailed in the first serious blow in a long line of battles against Siena. More than 1200 Sienese prisoners were captured and Montepulciano was temporarily saved.

The victory although important could not appease the discord within the city. In 1216 at a big celebration of a newly knighted Florentine a noble was stabbed. For the matter to be resolved without further bloodshed, it was arranged for Buondelmonte Buondelmonti, who was the attacker, to marry a girl from the Amidei family, a relative of the wounded victim.

The bride was not however renowned for her appearance and Buondelmonte decided to repudiate his promise and marry a beautiful girl from the Donati family instead. The insult from the Amidei family was not taken lightly. On the morning of his wedding, Buondelmonte all dressed up for the ritual was ambushed and killed right under the tower of the Amidei family.

The murder started a long vendetta that split Florence in two. On the one side, the Buondelmonti, the Pazzi, and the Donati led the side of the Guelphs and were mostly centered between Via del Corso and Porta San Piero, and on the other hand, the Amidei, Uberti, and Lamberti that led the Ghibellines and resided in the city sector more or less between Ponte Vecchio and the Piazza Della Signoria.

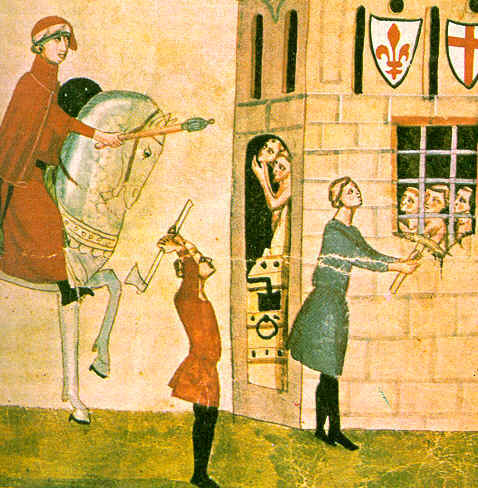

A vicious cycle of violence opened with fighting erupting in the streets and temporary victories proclaimed by both sides, members of the defeated being exiled from the city and their property seized. Most of the time the exiled would flee to a neighboring city-state, gather support from their counterparts and return to Florence, with more manpower. After and if they defeated their opponents, they would re-open a new cycle of blood and exile.

The establishment of various religious orders in the first decades of the 13th century, the Franciscans (Saint Francis himself arrived in Florence in 1211) who adopted the small chapel of the Holy Cross that would later become the Basilica Santa Croce, the Dominicans who resided around the Santa Maria Novella, the Augustinians and the Carmelites a bit later, did not have any effect on the mitigation of the political passions.

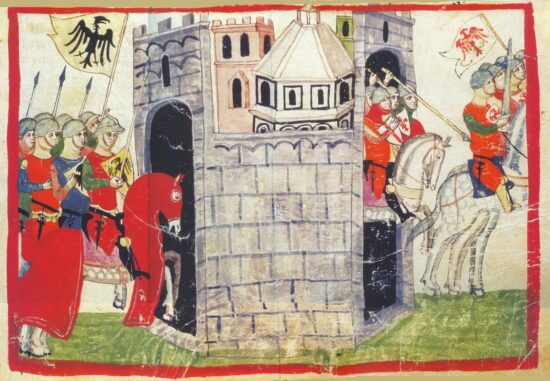

In November 1237 in the Battle of Cortenuova, the army of Emperor Frederick II crushed the allied forces of the Lombard communes, making the Ghibelline party dominant in Northern Italy and Florence. With the battles between the Imperial army and the Guelfs still raging, Frederick II installed his illegitimate son Frederick of Antioch as Podesta of Florence and General Vicar of Tuscany in 1245.

Although the Ghibellines and their leader Farinata of the Uberti family were there to welcome his arrival with enthusiasm and despite Frederick’s ruthless oppression of the Guelphs, he would be forced to re-conquer Florence with the help of his father’s army in 1249. After the death of Emperor Frederick II in 1250 the Guelphs took back control of Florence and Farinata degli Uberti found refuge in Siena.

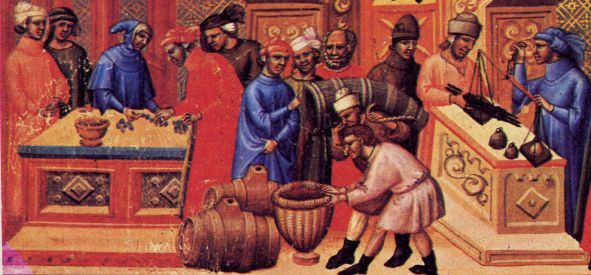

Dominated by the middle class, the new regime initiated an era known as the period of Primo Popolo, or people first. It was the first time the power shifted away from the old noble families towards the people that made the heart of the economy beat, the merchants and the artisans.

The introduction of a new coin, the golden fiorino in 1252, the first gold coin in Western Europe with a standard and consistent content proved to be a decisive move for the growth of the Florentine economy. The fiorino d’oro with the fleur-de-lis symbol of the city on one side and the other a figure of St. John the Baptist was widely used beyond the narrow borders of the city, throughout Europe and the Mediterranean basin, as money for important business transactions and large international payments and loans.

In a symbolic move, all the towers of the city had to be cut down to a height of 29 meters while at the same time the first version of the Palazzo del Popolo (the Palace of the People) is erected in Via del Proconsolo between Piazza del Duomo and Piazza San Firenze, incorporating the old palace, the Badia Fiorentina and several houses and towers in 1255.

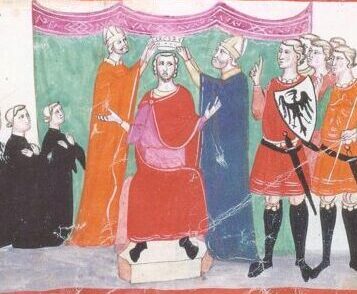

When Emperor Frederick II died at the end of 1250, the Ghibelline camp temporarily faltered and many towns rebelled spurred by Pope Innocent IV. Frederick II’s illegitimate son Manfred of Sicily, although he had just turned 18, quickly rose to the occasion forcing several rebellious cities into submission and defeating the papal army at Foggia in Southern Italy in December 1254. His coronation as King of Sicily in 1258 would give vent to the hopes of the Ghibellines throughout Italy.

Encouraged by King Manfred‘s coronation the Florentine Ghibellines revolted later that year only to lose again. A new set of exiles took place and although Siena had agreed in 1255 not to host any exiles from Florence, the Ghibelline city would not stay true to its commitment. That became the straw that broke the camel’s back for the Guelphs of Florence who felt they had to act before the King of Sicily.

A Guelph army of 35.000 from the cities of Florence, Bologna, Lucca, Prato, Orvieto, San Gimignano, San Miniato, and others first moved against a small joint army of German and Sienese knights that had moved against the small town of Montemassi in early 1260. All the German knights of King Manfred were killed and his insignia was dragged in the mud by the Florentines and exposed to public ridicule in Guelph city. At the same time, the first siege of Siena was broken when the reinforcements from Pisa, King Manfred, and other Ghibelline allies came to its aid in May 1260.

The massive Guelph army did not disband. On September 2, 1260, it reached Siena again. The Sienese who had already learned the news of the coming invasion had only mastered an army of 20.000 strong. Among them, Farinata degli Uberti served as the commander of their army, a part of it formed by the many Florentine exiles of the Ghibelline party.

On September 4, 1260, the two armies met right after the river Arabia, at a hill named later Montaperti (hill of death). In one of the bloodiest battles of the Middle Ages, the Florentines were crashed despite their numerical superiority. According to Dante and the Florentines, the unexpected defeat came after a betrayal by a (secret) Ghibelline man fighting for Florence, who managed to spread panic on the Florentine side after chopping off the hand of the flag bearer.

As a result of the nightmare of Montaperti and the heavy toll on men (an estimated 10.000 dead and 15.000 prisoners), the Guelph families of Florence left the city in fear of reprisals for Bologna and Lucca. The Florentine Ghibelline exiles returned to their hometown before the end of September of 1260. Farinata of the Uberti although finally in a good place would have to tackle another challenge, when his allies decided to make Florence an example for all Guelphs and raze it utterly to the ground. His strong stand changed the fate of his city but not that of the Guelph properties. 103 Guelph palaces, 85 towers, and 580 houses were destroyed.

The new Pope, Urbano IV (1261-1264) could not remain passive while his followers were persecuted. After excommunicating King Manfred he pressed on with the ex-communication of all the Ghibellines of Florence and Siena, creating a major problem for the merchants of the two cities, who now feared that every devout Christian in Europe would avoid working with them or deny payment. At the same time, he pleaded to Charles of Anjou, brother of the French King, to become the defender of Christianity in Italy and King of Sicily instead of King Manfred.

Charles entered Rome on 23 May 1265 and was proclaimed King of Sicily in January of 1266. In February 1266, leading an army of French and Italian mercenaries along with a large cavalry force of Florentine Guelphs managed to defeat the army of German, Italian and Saracen mercenaries of King Manfred in the Battle of Benevento. King Manfred of Sicily, the most hated enemy of the papacy was killed in battle. The Guelphs were again ahead of the game and that was enough for the people in Florence to rise and drive out the Ghibellines once more.

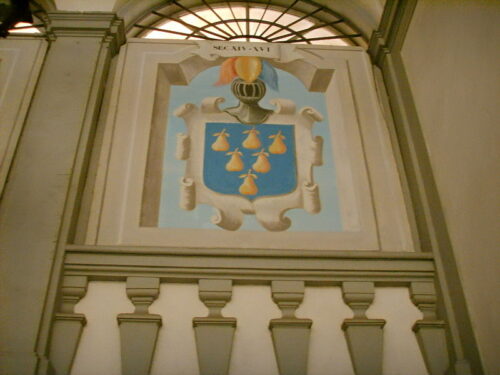

The new pope Pope Clement IV offered as a token of gratitude his coat of arms to the Guelph Party of Florence in official recognition of their contribution to the final victory, while Charles of Anjou, now officially Charles I of Sicily, was also elected Podesta of Florence for seven years. All the institutions abolished by the Ghibellines in their six years of power were reinstated.

The destruction of the Guelph homes and palaces would also not go unpunished. All the buildings belonging to the Ghibellines and especially those of the Uberti family that stood in what is now Piazza Della Signoria were destroyed with the condition, especially in the case of the Uberti houses, it was declared that no building should ever be erected in that accursed site. A few years later the Palazzo Vecchio, was built not in the center of the piazza but on its east side for that reason.

Although in some cities like Genoa the Ghibellines managed to recover by the mid-1270s, in Florence the Guelphs felt confident and strong enough to allow the repatriation of the exiled after 1280. A civic guard of one thousand men would preserve the peace in the city. It was during that time, that the greatest figure in the history of the Italian language, the poet, writer, and politician Dante Alighieri (born in 1265) started to form his rich intellectual credentials under the guidance of an important Florentine scholar named Brunetto Latini.

The 24 years old Dante took up arms in 1289 when the Florentines along with the rest of Tuscan Guelphs, went on to attack the last remaining stronghold of the Ghibellines in Tuscany, the city of Arezzo. The Battle of Campaldino in June 1289 was the final blow for the Ghibellines of Tuscany and the official beginning of the Florentine supremacy in the whole of the region, especially after the defeat of the main rival city of Pisa by Genoa a few years earlier (1284).

After 1282 the legislative and executive government of Florence was executed by the Priory of Arts also known as the Signoria consisted of three priors, elected by the members of the 21 guilds of arts and crafts. Their tenure lasted only two months to secure a maximum degree of mobility and avoid the empowerment of certain people at the expense of the republic.

In 1293 in the most important reform of the Republic since the abolition of the consular system, prior Giano Della Bella completely excluded the old feudal families from the government by making it necessary for a citizen to be eligible prior, to being an exercising member of one of the arts first. In addition, the priors were obliged to reside initially in the Tower of Castagna later in the Palazzo del Bargello where they remained in isolation outside of the public hearings.

In 1294 the city council decided to employ an architect that would help Florence express the self-confidence and ambition of the growing city. Arnolfo di Cambio had already worked under Nicola Pisano in Siena’s cathedral and was initially hired to work on a new cathedral in the place of the 5th-century church dedicated to Saint Reparata that seemed a remnant of a time long-passed. He would not however be confined to just one project.

In May 1294 in the presence of many bishops and members of the clergy, the mayor and the captain of the People, and the priors the men and women of Florence, with great pomp and solemnity, the architect began working on a chapel established by St. Francis of Assisi back in 1226. It would later be known as the Basilica di Santa Croce. The first stones of the new grand duomo on the other hand were laid in September of 1296. Its consecration would take place 140 years later.

Just when things seemed to be smoothing out, a new division in the field of internal politics would rock Florence again. A group headed by Corso Donati, a typical Florentine noble, in essence, a coalition between the nobles and the working class, proponents of a more conservative policy, also known as the Guelph Neri, the black Guelphs against the upstart merchants, the new money, proponents of a more loose relation with the pontiff, the white Guelphs, led by the politician, banker, and veteran of the Battle of Compaldino, Vieri de ‘Cerchi.

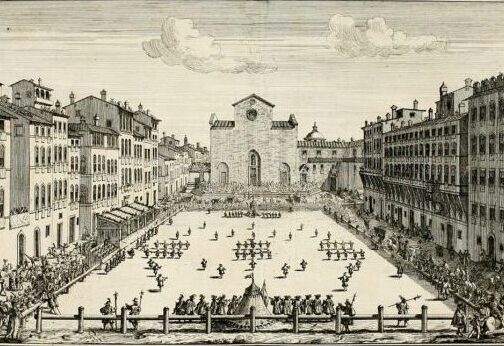

The feud came to a boiling point on May 1st, 1300, a day when Florence was traditionally celebrating the return of spring with dances and other festivities. Two groups of young men from the two opposing parties clashed with fists and swords, with one member of the Cerchi family ending up with a slit nose. That was the official beginning of open warfare between the two.

The Cerchi turned to the neighboring city of Pistoia which was similarly divided into rival factions and after securing more manpower, they entered Florence and drove out the Donati and the rest of the Black Guelph leaders in May 1301. The Blacks did not lay down their arms, however. They found their ally in the face of Pope Boniface VIII (as a white Guelph himself, Dante would reserve a special place for Pope Boniface VIII in his inferno/hell). The Pope placed Florence under an interdict and summoned a French prince (Charles of Valois), like his predecessors before him, to put an order in the city of Florence and take the Sicilian crown in return.

Probably because of weakness, the Whites did not raise any objection to the visit of Charles, who came to Florence on November 1, 1301. Five days later however Corso Donati burst into the city with a small group of followers and went straight to the town’s prison, which was packed with Black Guelphs. For six days the streets of Florence became a stage of violence and murder, women were raped and children were taken as hostages, houses were set on fire and people were tortured publicly in broad daylight.

By 1302 the Blacks had prevailed and the Whites (Dante among them) had left the city and their properties behind. Alas, Florence’s self-destructive factionalism did not stop with the expulsion of the Whites. Corso Donati started to antagonize his comrades and the Black camp split in two, with one part of it standing with him (the Donateschi) and the other with Rosso Della Tosa (the Tosinghi).

In 1303 Corso Donati sided with the Cavalcanti, a family of White Guelphs to defeat his former comrades leading to an unprecedented mess, temporarily resolved after the intervention of Pope Benedict XI and an army sent from the city of Lucca, that briefly controlled Florence.

In 1304 Donati managed to come out unscathed from an assassination attempt but by 1308 the city had had enough of him. When the decision of the Signoria, that sentenced him as guilty of treason against the commune came out, an angry mob swarmed his palazzo, forcing him to flee. In his attempt to escape, he fell from his horse and died. With his death and the expulsion of his followers, the city finally got its peace back.

Despite the bloodshed and the exiles, the population had increased considerably by 1300. A new set of walls, the sixth one, would enfold an area five times larger than the one before. The works in Palazzo Vecchio and the cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore proceeded in full swing, new palazzi and churches sprouted everywhere and new powerful guilds like the Arte Della Lana (its members processed the raw baled wool at numerous looms scattered throughout the city, unlike their rivals in the well established Arte di Calimala, who imported raw clothes and then dyed/finished it) inaugurated their grand new guildhalls.

At the same time, the Sienese bankers that dominated the world of money lending and finance in Western Europe in the 13th century were gradually losing ground to the more aggressive Florentines. In the 1290s a bankruptcy of a leading Sienese banker would give all the needed space to the Florentine families of the banking sector to grow and expand.

The families of the Bardi and the Peruzzi had already established their branches in England by 1290. By the 1320s the two families had become the main European bankers and their novel financial services like the bills of exchange, known today as checks, facilitated merchants throughout the European continent.

The booming economy created wealth and wealth generated confidence. Probably too much confidence would be unexpectedly shattered by the star of Uguccione Faggiola, lord and mayor of Arezzo, Pisa, and Lucca. S

eriously outnumbered by the combined forces of Florence, Siena, Pistoia, and Arezzo among others, the Ghibelline army of the three cities, reinforced by a contingent of 1,800 German knights crashed the Florentine alliance in the Battle of Montecatini in 1315. The defeat shocked the city they had to pay a huge amount of money in ransom while almost every family of nobles mourned a dead member after the battle.

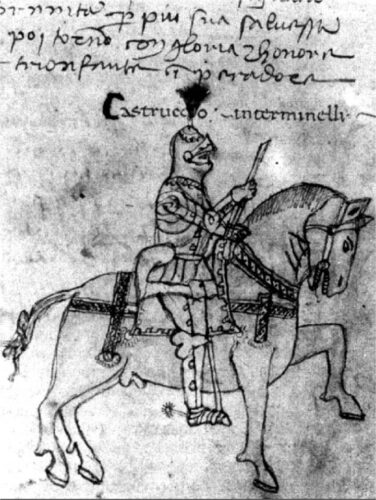

The star of Uguccione Faggiola would be very quickly outshined by his military commander, the main architect of the Ghibelline victory, Castruccio Castracani. After the battle, Uguccione saw in him a potential danger to his power and did not hesitate to send him to prison, with the intent to have him executed. A popular uprising in Lucca would save his life and acclaim him a Captain-General for life. In 1319 he resumed hostilities against the Florentines, breaking into their territory, burning and plundering everything in his way.

The conquest of Pistoia, a town very close to Florence (30 km) that had been under the Florentine rule for almost 70 years, did not leave any choice to the Florentines. With an army of 17.000, mostly French and German mercenaries, the Florentines moved to attack Castruccio‘s forces in August 1325. In the Battle of Altopascio on September 23, 1325, the military brilliance of Castruccio would triumph once more. The Guelph army was humiliated and the road to Florence was wide open.

Castruccio’ss army started to sack the territory and towns around Florence for days until it finally reached the city’s gates in October 1325 and started to celebrate his victory by running mockery processions. Castruccio died at the peak of his glory at a time when he was preparing to fulfill his dream of conquering Florence.

The imminent danger forced the city to entrust its fate in the hands of Charles, Duke of Calabria, Vicar-General of the Kingdom of Sicily (Naples) in January 1326. He would rule for just 12 months before the commune reasserted its independence and both Castruccio and Charles were dead (1328).

Despite the military failures Florence hadn’t lost its confidence. Despite the confidence, the military failures kept coming first in 1330-1331 with the unsuccessful attempts to take Lucca and Pisa and then by the forces of the Ghibelline lord of Verona, Martino Della Scala in 1339. In the meantime,e a great flood had swept away three of the four bridges that connected the two sides of the Arno.