Grown Up

While the 1700’s was a period of growth for most European cities, Catania had to start from scratch allover again. A crucial decision was made to intervene immediately with an overall project for all 77 cities that had been affected by the earthquake. Viceroy Giovan Francesco Paceco, Duke of Uzeda, a man of culture and scientific interests, was the man who carried out the task. He then entrusted the post of vicar general for the Val di Noto to Giuseppe Lanza, Duke of Camastra. Catania appeared totally destroyed and that tipped the balance towards the decision to rebuild on the same place but also to ignore the fortifications that kept the city enclosed for hundreds of years. The Duke of Camastra used military technicians and engineers to clear the rubble and took action against the marauders. In June 1694, with the participation of representatives of all the orders of citizens, he prepared the general plan. An ideal line divided the city into two parts, assigning two different conventional prices to the land: the one to the west, in which the price of the land had been devaluated by about one third, was destined to accommodate, as before, the popular neighborhoods; to the east were concentrated the buildings of the secular and ecclesiastical nobility. The wide streets, interrupted by frequent and regular squares, were an anti-seismic precaution. The main road axes were defined, superimposing straight lines on the ancient winding course of the streets and underlining, in the western part of the Corso, the ancient layout of the Roman city. The architectural jewels of the city, the Cattedrale of Sant Agata, the Monastero di San Nicolò, the Church of San Benedetto, the Palazzo degli Elefanti (town hall), were all reconstructed in Sicilian Baroque that became the common denominator during the 18th century.

The fervor of the reconstruction sets the tone for eighteenth-century Catania life; for decades the city is a whole construction site, which attracts all sorts of construction workers and new inhabitants, which sets the economy in motion, which adopts new techniques and puts them in use right away. A precious experience for architects from Catania, Messina, Palermo, and Tuscany. Among all, Vaccarini is perhaps the one who left the clearest mark, both for the large number of buildings he cared for and for the long period of his work in Catania.

Certainly the enormous effort of reconstruction was due to the conspicuous building investments made possible by the feudal revenues accumulated by the rich families of the upper class, the Church, the religious orders (particularly impressive is the commitment of the Benedictines in rebuilding the monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena in the style of palace). But it was in this way that the city was able to overcome the crisis of the first decades of the eighteenth century, which saw Sicily pass from Spanish dominion to the Savoy (1713-1720), then to the Austrians (1720-1734) and finally to the new Bourbon dynasty, and all this without an actual enforcement of great changes or the birth of great hopes, or even conflicts not even between State and Church.

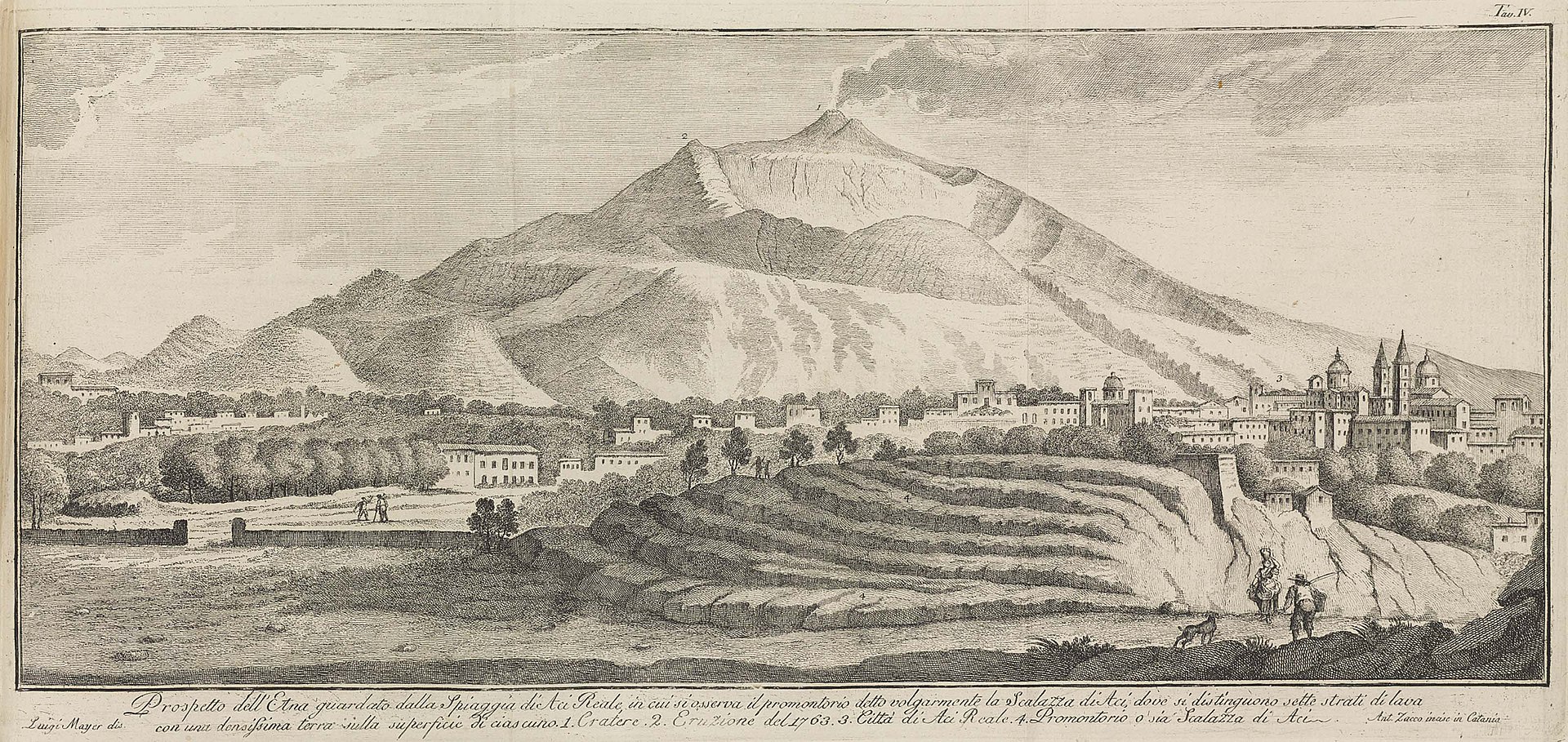

The surest sign of this vitality, in addition to the expansion of the urban fabric itself, is the story of culture. First of all, there is the increased importance of the “Studio” – the University – which, under the prevailing impulse of doctors and jurists, had already laid the foundations for a new location and expansion even before the earthquake; the Palazzo dell’Università completed in the 1690’s is now among the first to give a new prestige to the reoriented via Etnea, placing itself halfway between the town hall and the church of the ruling elite, that of S. Maria dell’Elemosina (Collegiata), rebuilt on the same place but reoriented to overlook the new main road. The University is a terrain of conflict between the ecclesiastical and secular leadership, in an era in which governments are beginning to take control of culture themselves. Private study centers, private libraries, associations, academies proliferate. The terrible experience of the earthquake and the looming of the volcano direct the cultural debate towards a concrete progress in the geological, mineralogical and volcanic sciences; thus the bottleneck of the dispute between science and faith is overcome, and with the work of the canon Giuseppe Recupero (1720-l778) the foundations of a rich heritage in the natural sciences are laid, which will be continued in the nineteenth century.

The dominant personality is that of the Prince of Biscari, Ignazio II Paternò Castello (1719-1786). A figure of European level, archaeologist, antiquarian and patron of arts he set up a library and most importantly a museum that attracted the admiration of all visitors and became a study and research center. The library and museum of the Benedictines competed with this large private collection, also a center for discussion and for classical, philosophical, historical and naturalistic studies. The historian Vito Maria Amico (1677-1762) and later the naturalist Emiliano Guttadauro (1759-1836) are among the most prominent figures of the time.

The significant demographic expansion (in 1798 it already had 45,000 residents), the concentration of important economic activities especially in the textile sector (silk), and the control of the surrounding countryside make the eighteenth century the period in which Catania definitively overtook other important centers of its hinterland. After 1770, however, building activity slowed down considerably. In part this was due to the conclusion of the projects undertaken; but also due to the agrarian crisis and the difficulties of international trade. In 1764 the city was devastated, along with the rest of the island, by a terrible famine. The privileges that allow the nobility to control the production and export of grain tend to strengthen the positions of the aristocracy, and to stabilize the economy of the large estates. This, for Catania, above all means the increased power of those who, like the Biscari princes, dominate the plain. As for the rest of Sicily, an attempt of feudal reform takes place in the 1770’s and 1780’s. The years of the Napoleonic wars in the Mediterranean are for Sicily the years of the English occupation 1806-1815) and the constitutional transformation with the legal end of feudalism. The city of Catania is not able to take advantage of the commercial activity that takes place in the vineyards of its own territory and the trade of Etna wines with the British army due to lack of a modern port. In 1798 and 1799 Catania was shaken by popular revolts for bread. The growth of a popular rebel stratum is looming, even if this does not give rise to any revolutionary movement on the French model. It does however provide the deputies of Catania for the Sicilian Parliament, who, between 1810 and 1815, sided with the most radical wing.

The Bourbon administrative reform of 1817 established seven substantially equal provinces in Sicily. The hierarchy between Sicilian cities was redefined, and the terms of the ancient rivalry between Palermo and Messina altered. Catania found itself the capital of a vast territory, the seat of courts, the provincial administration, various administrative offices. The population, which at that time had dropped back to 40,000 inhabitants, rose to 52,000 in 1834, starting an extraordinary secular gallop: 68,810 inhabitants in 1861, 90,000 in 1880, 150,000 in 1900, 230,000 in 1931, up to the present 363 thousand. The primary reason for this continuous growth, which has no parallel on the island, is the exchange between the countryside (and the smaller towns) and the urban center. Catania is increasingly becoming a pole of attraction for trade, industry, consumption. In the first half of the century, the main industrial activity in Catania was the textile sector. Weavers and artisans – together with the fishermen and the people who live in the port alongside the group of marginal or unskilled workers who form the backbone of the proletariat. On the other hand lie the bourgeois with predominantly mercantile interests who set the tone of the middle class.

It is still agriculture however that forms the wealth of Catania, both in the sense of wealthy or noble provincial families who move to the city, and for the participation of citizens in land investments. The city thus built the role of market, distribution center, and cultural pole: theaters, reading rooms, the University and academies, cultural and political periodicals. But for all this it still has to compete with other urban centers. Vincenzo Bellini, one of the most famous opera composers in the world is born in Catania in 1801. He would move to Naples where he completed his studies and presented his first operas. He would work in the Scalla of Milan and then in Paris where he died in the young age of 34 years old in 1835. His body was interred in the cathedral of Catania where after a solemn funeral attended by thousands of people from Catania, was placed in a monumental tomb, sculpted by Giovanni Battista Tassara.

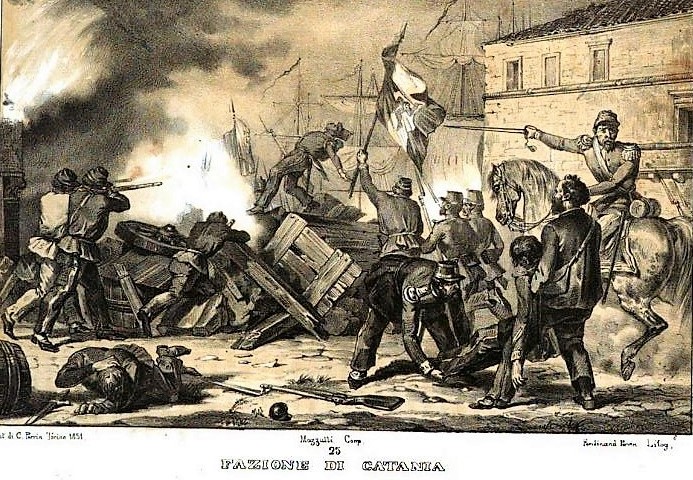

Before the Unification, the city was still relatively poor in hotels, cobbled streets, public places. The divorce between the city and the Bourbon regime took place in 1837:after the outbreaks of cholera, centered in Syracuse, the monarchy was accused of having spread the poison out of hatred to the people. In reality, the difficult alliance between moderate constitutional nobles and leaders was strengthened by the blindness of the Bourbon repression which hit back indiscriminately. After then, in 1848, in 1860 with Garibaldi, and again in 1862 with the failed Garibaldi expedition of Aspromonte, Catania provided the Risorgimento (Italian unification) with Masonic and Carbonari, Mazzinian and moderate conspirators, consolidating an image of a democratic city.