Early Adulthood

After the death of Martin the Elder in 1410 the crown of Aragon went to his nephew Ferdinand I, second son of King John I of Castile who was chosen as the next king in 1412. In four years the new king died and the crown went to his son Alfonso the Magnanimous. The territories of the Crown of Aragon had officially passed under the dominion of the royal dynasty of the Trastámara , ruling in Castile. In May 1416 Alfonso the Magnanimous, summoned all the barons and prelates of Sicily in the hall of the Parliament of Castello Ursino, for the oath of loyalty to the Sovereign. This would be the last act of Catania as the capital of the kingdom. Palermo would again take the helm as the most important city of the Sicilian realm. As a form of compensation to Catanians the new King, would grant the charter of the first university in Sicily in 1434. The papal bull of Eugene IV which authorized the constitution was issued on April 18, 1444. The new university would include the teaching of theology, civil law, medicine, surgery, philosophy, logic, mathematics and liberal arts but it would be firmly controlled by the bishop who would serve as its chancellor. The first public lessons took place in a building in Piazza del Duomo, next to the Cathedral of St. Agatha at the end of 1445 but they eventually moved to the Palazzo dell’Università in the late 1690s.

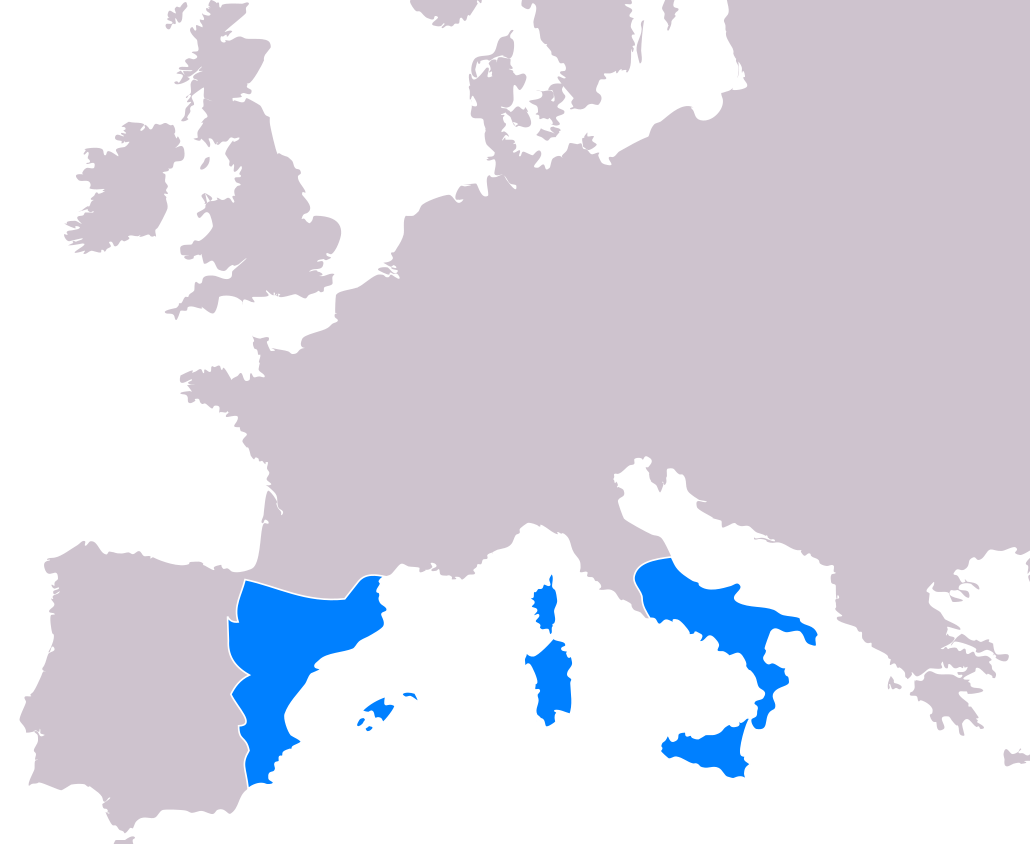

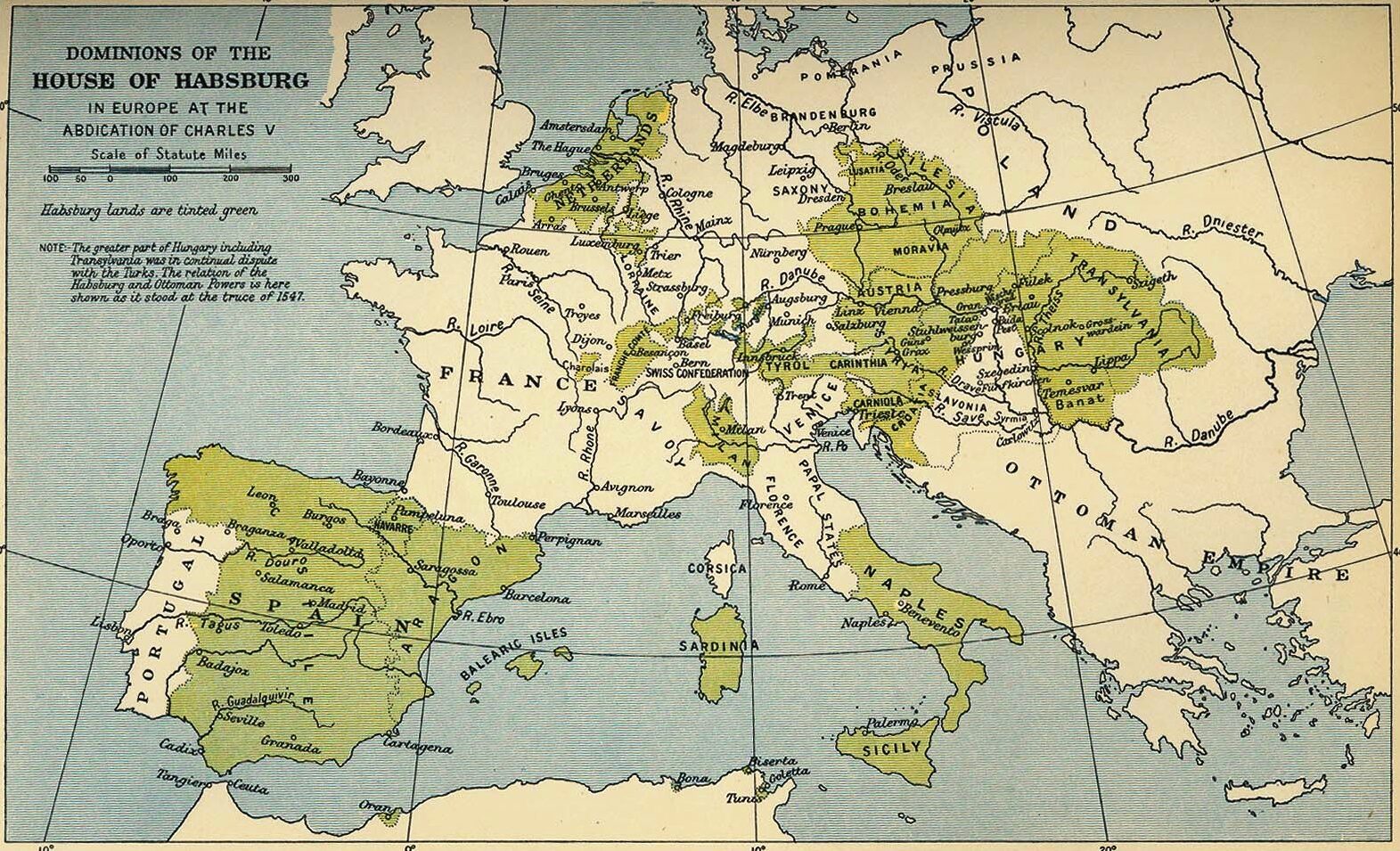

In 1442 Alfonso the Magnanimous conquered the Kingdom of Naples assuming the title of Rex Utriusque Siciliae and formally unifying the two kingdoms once more. From now on the kingdoms would be referred to as the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. Most of the time the rulers remained in Spain; Aragon and Castile were united in 1479 to form what was to become the Kingdom of Spain. The Spanish kings would send governors or viceroys to rule the island in their name and the Sicilians had to bear the cost of the Spanish wars against the maritime cities of northern Italy.

During the fifteenth century, the city experienced a renewal of the elite that occupies the public seats, both ecclesiastical and civil posts. A dozen feudal families manage to control to a large extent the mechanisms of the viceroy government. The most important municipal offices were the Captain of Justice, the Patrician, and the six members of the council called senators. After 1412 the citizens had obtained the right of vote, that is the right to elect senators, albeit by choosing from very controlled lists. Hindered, suspended and resumed several times, the ballot system nevertheless represented a democratic way of decision and collective legitimation of the municipal government. In general there was a process of formation of an urban underclass which caused a strong growth of the population of the big cities of the island, while the rural population decreased in proportion.

There was an exception to the rule of the closed high ranking caste in the face of Giovanni Battista Platamone, a law graduate of Greek origin who made a name of himself as competent lawyer so much so that he was promoted to the highest ranks of the Spanish bureaucratic administration, making a fortune and even lending money to the Spanish king himself. He would erect a showy palace in Catania , which contended with Palazzo Biscari for the reputation of the most luxurious and representative palace in the city. There was a process of formation of an urban underclass which caused the strong growth of the population of the big cities, while the rural population decreased in proportion.

In the sixteenth century, Catania was affected, like the rest of the island, by the overall reformation of the Mediterranean area. Ferdinand II of Aragon, together with Isabella of Castile, reunified Spain, laying the foundations that would make their grandson Charles V the emperor on whose lands the sun never sets. Since, after the Fall of Constantinople (1453), a similar process of concentration of power took place in the east with the Ottoman empire. Sicily was now a frontier region between two worlds that were often at war with each other. The Mediterranean trade, which Catania counted on for its growth, suffered and with it so did the people.

Before the end of the century Sicily would be immersed in a religious regress, first with the introduction of the Spanish Inquisition in 1487 and five years later with the expulsion of all the Jews from the island. It is estimated that in 1492, the time of the Alhambra Decree there were as much as 25,000 Jews in Sicily and more than 2,000 in Catania in particular where the Jewish community had been present since the Roman times. By the time of Charles V there were no practicing Jews left in Sicily. While the north of Italy was entering the glorious historic period of Renaissance, the South entered into its very own dark ages, with the Church and the Spanish crown tightening a noose that was already tight enough after the emergence of the Ottomans on the east.

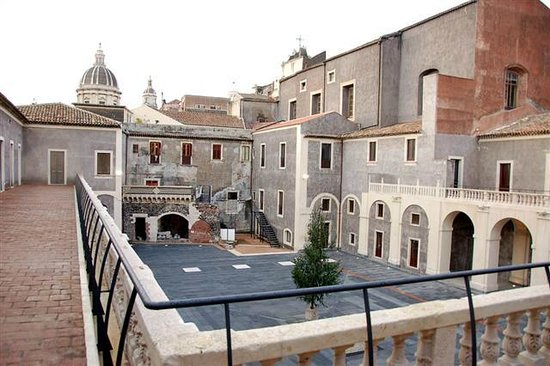

Despite its geographical importance Sicily lost its political weight inside the vast Habsburg Empire, especially after the opening of new routes for world trade outside the Mediterranean. On top of that the government of the southern regions of Italy and Sicily was centralised in capital cities like Naples and Palermo, leaving no room for meaningful reforms that would revitalize the economy of the rest. Against all odds the evidence during the 1530’s point to a vital and dynamic city, with a tendency towards demographic increase an expansion of crops in the Etna area, public interventions in the urban area, construction of new palaces by the clergy and nobility, a culture of decoration. The most tangible sign of change lies in the reconstruction of the walls (1540-1560). A series of natural disasters between 1536 and 1537, eruptions, earthquakes, explosions that shook Mount Etna and destroyed inhabited areas, vineyards, plantations in the hilly area and the worsening of the political-military situation in the Mediterranean and in Europe, brought about a widespread climate of fears and anxieties. The battering barrage for Catania continued in 1576 when a major part of the population died due to the plague. A few years earlier in 1558 in the presence of the Viceroy of Sicily Juan de la Cerda , Duke of Medinaceli we have the construction of the Benedictine Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena, a construction that would evolve to be a jewel of the late Sicilian Baroque in the 17th century. The population of the city at that time was around 20,000.

The university of Catania would help keep the city in the first tier of Sicilian cities but the commercial activity was lagging behind due to the lack of serious investment that would facilitate the naval trade conducted by the big ships of the 17th century. Agricultural production and exports based on wheat and wine from the wider region helped keep on an even keel in the local economy in the first decades of the century. In the decades that followed however, the city seemed to lose its vigour. Palermo, was now the administrative capital and privileged seat of the high nobility. The equalization (1622) of the Senate of Catania to those of Palermo and Messina would not account for much. Famines and plagues mark the growing administrative powerlessness of the Spanish regime. Politically, Catania too is torn by popular uprisings which correspond to more general crises such as the Revolution of 1674-78 that saw thousands of people taking up arms against the nobility of the city. The revolt was an outburst of the common people against the bad government of the city and the town-customs taxes. For a brief time the rebels took the control of the city but their quick disintegration and transgressions would turn moderates against them, with the city garrison and nobility taking back control after a few days of fighting.

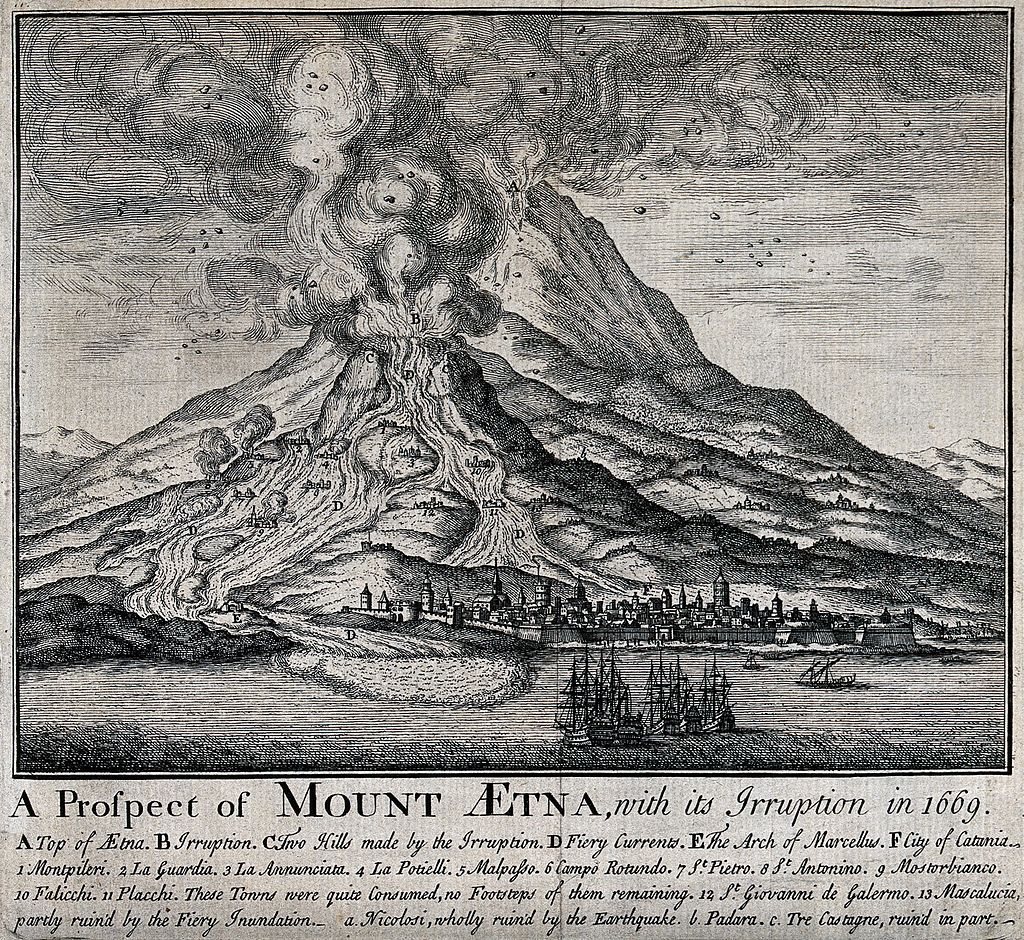

The whole culture of the city at the time seems to revolve around religious determinism, with its frequent recourse being the hope of the miracle: the veil of Sant’Agata will be carried in procession against the plague in 1592 and again in 1624; against the lava of Etna in 1536, in 1579, in 1636 and 1654. The eruption of 1669, however, inflicted a very serious blow in Catania. Thousands of hectares of cultivated land were destroyed, the lava ravaged the inhabited area from the north and west, after it passed trough the city walls, surrounding the Ursino Castle away from the sea and burying its moat and ramparts. Just when the city had started to heal its wounds a new more catastrophic disaster would spread havoc in the southeastern part of the island. The major earthquake that hit Sicily in January of 1693, had its epicenter just off the coast of Catania and had an estimated magnitude 7.4 on the moment magnitude scale (the strongest ever recorded in Italy). At least 70 cities, towns and villages were devastated but Catania experienced the hardest shock with much of its medieval as well as ancient urban fabric, especially the traces of the Greek city laying in ruins. Out of a total population of 20,000 more than 12,000 were killed. Some estimates raise the number to 16,000. It was a total catastrophe.