Maturity

The time of maturity of Bologna begins at the latter part of 19th century. As in most cities in Europe, the population of Bologna exploded in the latter part of the 19th century (From 115.000 in 1871 to 153.000 in 1897). In the new political situation, Bologna gained importance for its cultural role and became an important commercial, industrial, and communications hub.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the old walls were destroyed (except for a few remaining sections) to build new houses for the population. Bologna had gained a reputation for the production of many types of food, such as the famous sauce since the 18th century. During the nineteenth century, the city serviced an area where the economy was based essentially on agriculture. The eighth centenary celebrations of 1888 served also as an attempt to revive the city’s economy by linking it more directly to the University.

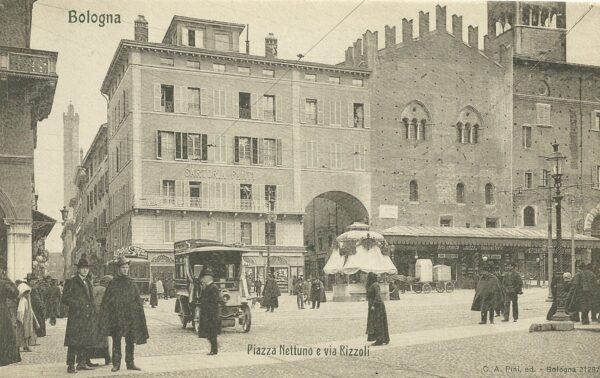

By 1890 the enlargement of via Rizzoli would lead to a great extent to the destruction of the ancient Mercato di Mezzo. At the same time the via dell’Indipendenza, via Farini, and via Garibaldi were well underway. The expansion of the city beyond the walls radically changed the cityscape and moved public opinion and the civic authorities toward a future of an open city. After all the wars between Italian city-states were a thing of the past.

The works lasted until 1920 but most of the ancient gates (ten out of twelve) were kept in place. The historic center was also kept intact. Although the political situation entered a phase of turbulence with the rise of fascism and the economic crisis of the 1920s with industrial, agricultural, and public service workers being engaged in more than two thousand strikes and countless political demonstrations.

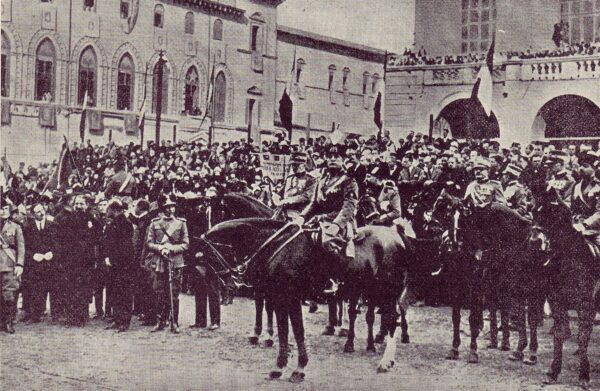

After 1924 any notion of constitutionalism was crushed by the fascists and Mussolini who would not have it easily despite their efforts. Several attempts of assassination against Mussolini were carried out in the first years of his rule. In October of 1926, a shot was fired at Mussolini as he rode in an open car through Bologna but the attempt was unsuccessful.

A 15-year-old boy that was supposedly the culprit was lynched by an angry crowd of Mussolini supporters. Many historians today have come to the conclusion the boy was innocent and the affair was either a put-up job or a plot between Fascists. The attempt resulted in laws creation of Mussolini’s secret police.

Despite the political divisions, the growing labor militancy expressed through a constantly increasing number of strikes and demonstrations, despite the soaring inflation of the 1920s, the industrial production in Bologna would register its first iconic brand in 1926 with the emergence of the Maserati automobile company, that based its logo (trident) in the famous Neptune fountain of Bologna.

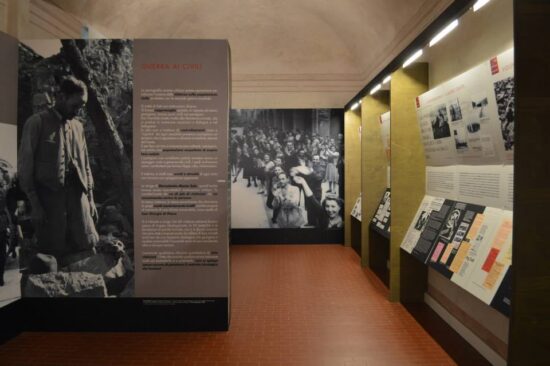

During the Second World War Bologna was a key transportation hub for the Germans but it was also a center for the Italian Resistance characterized by the activity of the partisan groups. In July 1943, a massive aerial bombardment destroyed a significant part of the city center. After the armistice of 1943, Bologna became the center of the Italian resistance movement. Its capture by the Polish 3rd Carpathian Infantry Division on April 21, 1945, led to the liberation of the Po Valley and the collapse of German defenses in northern Italy.

The bombings and battles between allies and Germans would result in the death of more than three thousand people from Bologna up to the end of the war. After World War II the city became a stronghold for the Italian Communist Party. After the conflict, many industries were severely damaged, such as rail and road networks, water, electricity, sewage, and gas were severely damaged. Subsequent administrations undertook the massive task of restoring the city to its former splendor.

One of the epithets that are most often heard about Bologna is “the red”. This is not only because of the omnipresent color on buildings, curtains, and churches but also because throughout the second post-war period the municipal administration was the flagship of the left. The name, therefore, took on a clear political connotation since the establishment of the first post-war government in 1946. The elected mayor, Giuseppe Dozza, became the protagonist of a revolutionary reconstruction project, based on transparency, self-management, and the fight against centralism typical of fascism.

Between 1951 and 1953 the consensus for Dozza remained constant and the mayor was personally involved in all the phases of reconstruction, especially in relations with the central state. On the cultural side, the initiatives put in motion by the local government were numerous, starting with full support for the University of Bologna which was on the way to becoming one of the most advanced universities in Europe.

After the victory over Dossetti in 1956, a “second season” of the Dozza government began. In the following ten years of administration, thanks also to the favorable economic situation of the 1960s, the ring road, the popular districts, and the large infrastructure projects Bologna became a great modern city.

Bologna is today a rich and important industrial and commercial nucleus. The 380,000 inhabitants live at the most important motorway and railway junction in the country; the historical center (which, after Venice, has remained the most intact of all the Italian cities) is surrounded by modern buildings, centers for trade fairs and conferences, and new residential areas.

The city and its residents carry their historic heritage with pride and confidence, striving for progress that does not sacrifice any of the features that make it distinct, and timeless, a testimony of the architectonic and historic continuum. Bologna is the capital and the largest city of the Emilia-Romagna of Italy. It is a vibrant, youthful urban center, oozing with culture and Italian vibrato.