Childhood

After Constantine the Great Christianity became the norm, the power center of the Empire moved east to Constantinople and the Germanic tribes started pushing more and more into the Western Empire’s territories. The decline of the West echoed in every city of Italy until the Western Empire fell to the Goths.

Most cities on the Via Emilia were under the rule of the Ostrogothic Kingdom after 488 with the consent of the Byzantine Emperor. Bologna’s perimeter was gradually reduced and religion took the role of the connecting tissue, a primitive social service of a tumultuous time. One such role was filled to a great extent by the Bishop of the city Petronius.

A member of a noble family whose members occupied high positions at the imperial Court at Milan and in the provincial administrations at the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth centuries was elected and consecrated Bishop in 432. He erected the Church to Saint Stephen (Santo Stefano) over a temple of the goddess Isis, in imitation of the shrines on Golgotha, the Church of Santa Lucia, and Santi Bartolomeo e Gaetano. When his relics were discovered in 1141 another church was erected in his honor, a second San Petronio Basilica at Piazza Maggiore. Saint Petronius is venerated in all Christianity and is still the patron saint of Bologna.

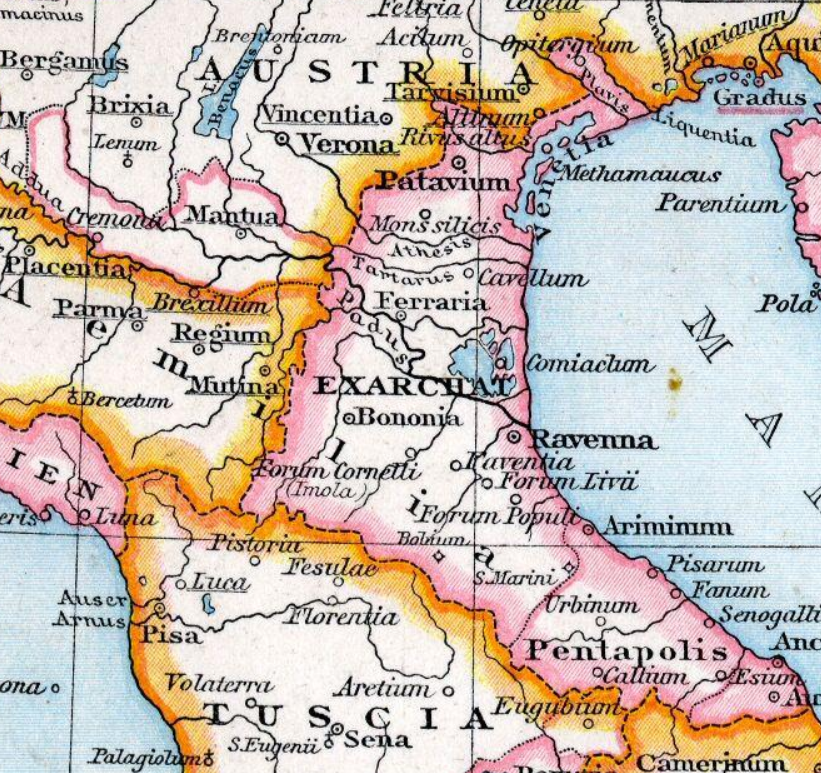

After the mid-6th century, Constantinople changed its stance. Emperor Justinian was determined to take back control of Italy and reunite the Empire. A long and bloody war against the Ostrogoths with General Narses and General Belisarius at the forefront turned Ravenna, the capital of the Goths until the year 540 into the capital of the Byzantine Exarchate.

The return to roman rule would have to be imposed with the sword in many areas but in 568 Emperor Giustino II recalled his general back to Constantinople due to protests by the Romans over fiscal oppression. In that same year, the Lombards invaded the Italian north. Around that time a series of stone crosses were placed on ancient overturned columns and were often protected by small chapels, located in the nerve centers of the urban fabric, such as crossroads and squares.

The oldest seems to have been placed between the end of the 4th and 5th centuries just outside the selenite circle, at the four cardinal points, near four of the city gates. The stone crosses were rebuilt and replaced several times, and those now visible are all dated between the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Byzantines also divided the city into 12 sectors, called horae and at any time of day and night, the inhabitants of the sector on duty were entrusted with the defense of the city which was now protected with an encircling wall known as the Circle of Selenite by the blocks of selenite, a chalky mineral very common on the Bolognese hills.

In 726 the Lombard King Liutprando decided to take advantage of the general discontent caused by the iconoclastic policy of the Byzantine emperor Leo III and the dispute between the Church of Ravenna and Rome. The tax burden imposed by the Byzantines on the Exarchate of Italy was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Revolts broke out against the Byzantine Empire in several cities.

Liutprand seized his chance, crossed the Po river, and invaded the Exarchate, occupying Bologna. Most of the Byzantine territories fell to the Lombards by 732 when the Eastern Empire tried to reconquer Bologna but was crushed by the Lombard army. The Lombards who were now Christians made a pact with the Pope and the Byzantines kept Sicily. During the Lombard time, the city declined to the point of being a simple castle that maintained however its important military and administrative role. Minor disputes between the dioceses of Bologna and Modena were administered by the Lombard king himself.

The Lombard presence is evidenced in particular in the addizione longobarda, a group of fortified buildings built close to the Circle of Selenite (first city wall) between the current Strada Maggiore and Via Castiglione. These buildings practically included the first nucleus of the Santo Stefano complex where many of them were buried. Today the evidence can be seen in the circular type of the roads due to the defensive installations of the Lombards. The Bolognese area that was mostly Lombardized appears to be the eastern one while the western part falls into a state of complete neglect.