Early Adulthood

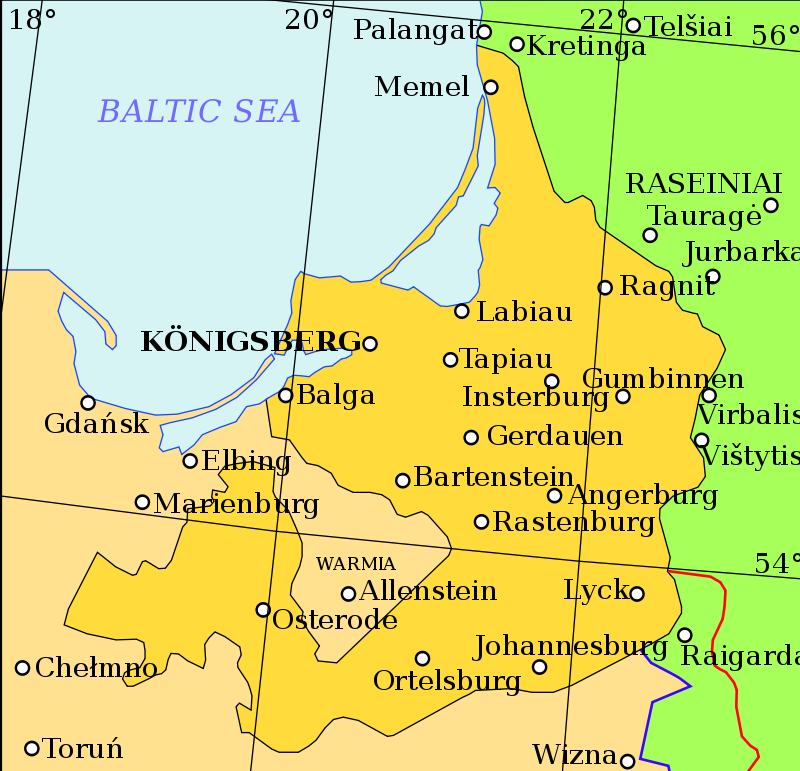

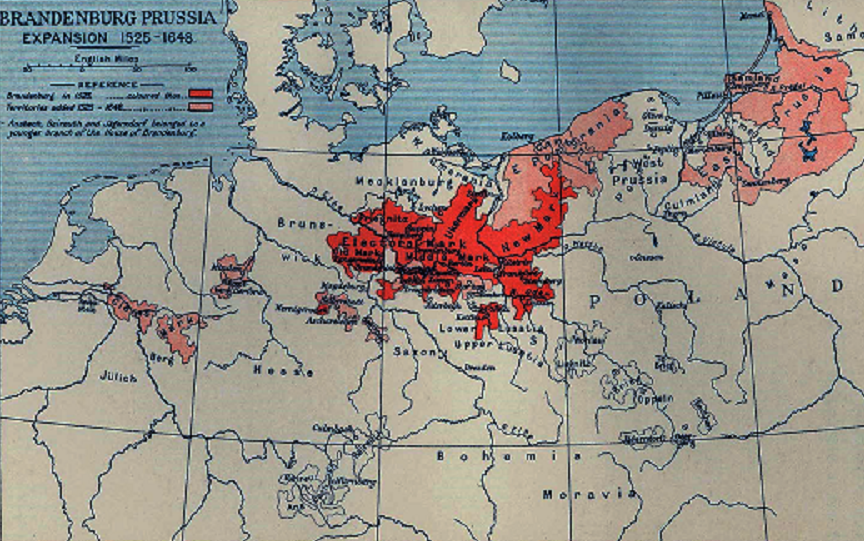

The Early Adulthood era for Berlin begins with the coming of the 16th century. Since the 16th century, the electors of Brandenburg had laid their claim in the succession of the Duchy of Prussia mostly through a marriage policy. In 1605 Joachim Frederick of Brandenburg (r.1598 – 1608) became regent of the Duchy of Prussia through his second marriage with Eleanor of Prussia.

Upon his death in 1608, his son and heir John Sigismund (r.1608 – 1619) also became the Duke of Prussia. It would be a long-lasting relationship and not always a happy one. At the time Berlin had a population that revolved around 10,000 people. In their great majority, they were Lutherans, which meant that the entire Brandenburg state and its religious affairs were overwhelmingly Lutheran too.

The influence of the Calvinists, on the other hand, was initially limited to a few important personalities, including the new elector, who publicly took communion according to the Calvinist rite in 1613. The attempt, with the public confession of the elector at Christmas 1613, for a second Calvinist reformation in Brandenburg failed from the very beginning.

The elector’s change of denomination, which had already taken place in 1610, was criticized by the estates in the committee, and demanded a return to the Augsburg denomination. The result was a centuries-long religious discrepancy between sovereign and subjects, which made a minimum at least religious tolerance necessary. In 1615 the anger of the Lutherans in Berlin erupted in a tumultuous form. Looting of the homes of leading Calvinists.

Calvinism remained an elitist minority religion of the dynasty. While Berlin’s other churches, subject to Lutheran city-council jurisdiction, remained Lutheran, Berliner Dom (city’s cathedral today), the Hohenzollern’s family church and official burial place, became Berlin’s first, and until 1695, only Calvinist church.

Up until 1618, the population of Berlin had continued to grow to reach 12,000 in total. The unrest between Lutherans and Calvinists had forced John Sigismund to allow his subjects to be either Lutheran or Calvinist according to the dictates of their consciences. Brandenburg-Prussia would be a bi-confessional state.

When the Thirty Years’ War broke out in 1618 within the Holy Roman Empire, Protestant German states fighting the Austrian Hapsburgs and their German Catholic allies, Brandenburg and Elector Georg Wilhelm (r.1619 – 1640) tried to remain neutral. It wasn’t a war he or his subjects could escape from.

By the end of the war in 1648, the whole of Brandenburg had been ravaged and the population of Berlin was reduced in half its buildings lay almost completely in ruins. The Elector’s policy had proved to be catastrophic for his country. George William withdrew in 1637 to Prussia, leaving his devastated by the war country to his son Frederick William who took over Brandenburg-Prussia officially in 1640, while his father enjoyed his retirement.

The new Elector had spent his apprenticeship in the Netherlands at a time when the former Habsburg country was living through its golden age. Frederick William had been impressed by the accomplishments of the Dutch and his admiration had very much affected his view of the world and most of all of effective, modern governance. His economic and political ideas were shaped accordingly. With the marriage of the daughter of governor Friedrich Heinrich of Orange, close family contacts were established with the Dutch elite.

The new Electress was followed by Dutch artists, craftsmen, builders, farmers, and merchants who brought modern techniques and production methods to the country. In Berlin and Potsdam in particular, a “Dutch colony” established itself, which was occupied with the expansion and redesign of the fortifications, the expansion of the city palace, and the construction of streets and canals. Seeing the benefits of religious tolerance in the Netherlands and being a Calvinist, Frederick William invited the Huguenots suffering persecution in France to Brandenburg.

Of the 20,000 Reformed religious fugitives who responded, only 6,000 settled in Berlin. Their professional efforts as tradesmen, entrepreneurs, and financial dealers bolstered the city’s industrial upsurge. Jewish families persecuted in Austria were allowed to settle in Berlin once more. The new canals, provided a direct link with Wrocław in the east and Hamburg and the open sea in the west by the year 1670. Brandenburg acquired a state navy, the first in history (Kurbrandenburgische Marine), leading to some short-lived colonies like Arguin, the Brandenburger Gold Coast, and Saint Thomas.

Full sovereignty over Prussia was also achieved by 1657. Berlin prospered again. The nobility, who now increasingly moved to the cities, the court of Brandenburg-Prussia, who resided in the residential landscape of Berlin, revived the production, consumption, and trade of goods in the luxury and fashion sector.

At the end of Frederick William’s reign (1688), 20,000 people lived in a city that had received a contemporary fortification ring, a pleasure garden and a representative avenue (Unter den Linden), and a series of grand new palaces like Kommandantenhaus, Kronprinzenpalais, the Börse of Berlin (Berlin Stock Exchange Building) and the Schönhausen Palace.