Childhood

At the beginning of the 14th century, the area on the outskirts of Kölln was reshaped by the construction of the Dominican monastery and church. The population of Berlin had doubled and the central market had moved from Molkemarkt to St. Mary’s Church due to the need for more space. The Franciscans had already settled in Berlin as early as the middle of the 13th century with their monastery being near the Hohes Haus in today’s Klosterstrasse.

At the time Berlin was already almost twice as large as Kölln. The two towns joined forces in 1307 to secure and expand their rights vis-à-vis the sovereign. Twelve councilors from Berlin and six from Kölln sat in the town hall that stood on the site of the northwest corner of today’s Berlin Town Hall. A common city wall was built. The cities thus formed a unity with the outside world, but each kept its administrations and households.

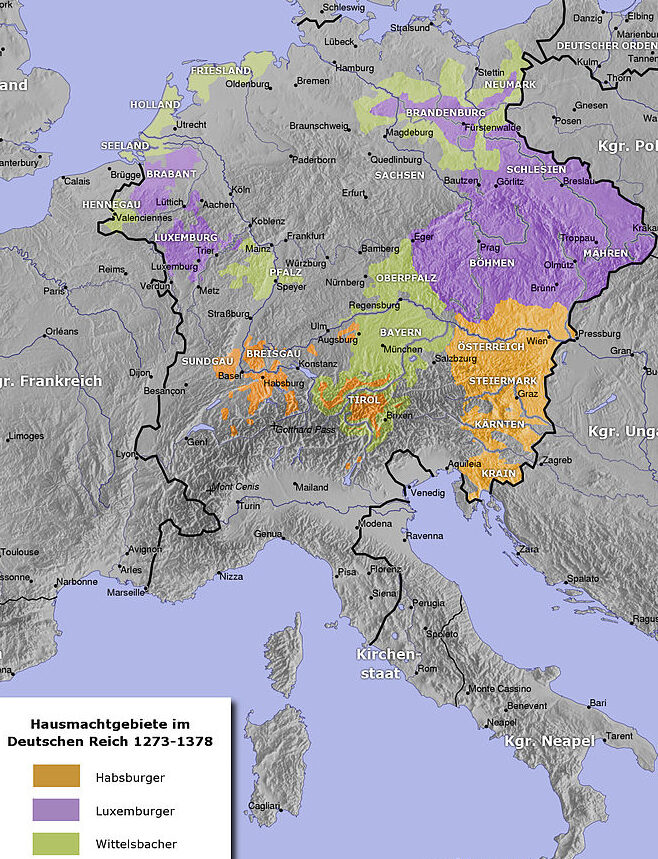

At that time, Brandenburg was still ruled by the Saxon Ascanians, descendants of Albert the Bear. When the last Ascanian died in 1319, Berlin and Brandenburg became the victims of a long struggle for rule between the Luxembourgers and the Wittelsbachers that would disrupt trade and devastate the region.

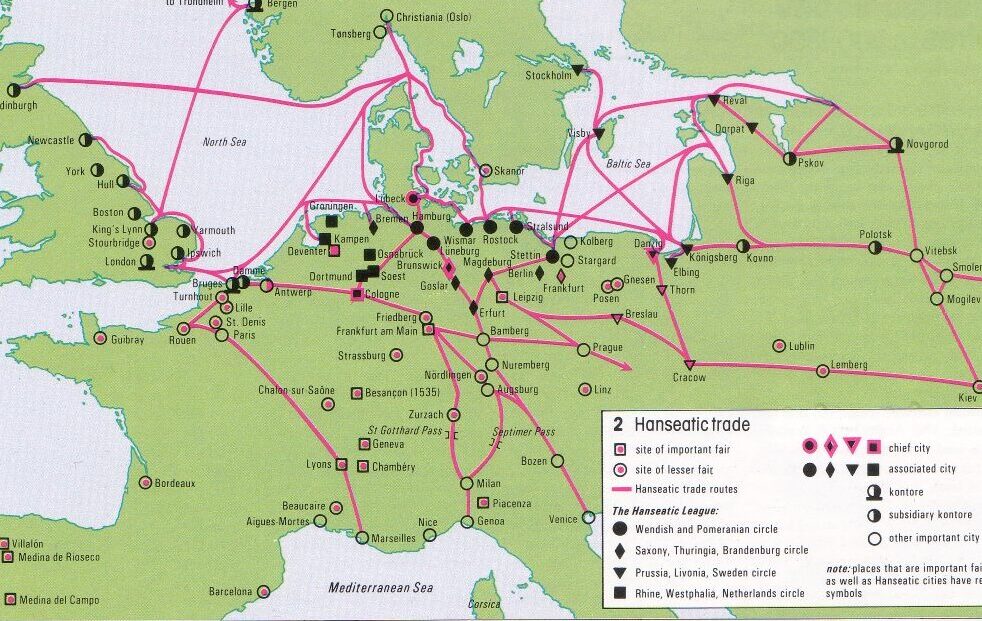

The Margraves Johann I and Otto III had bestowed city rights, exemption from duties, and the right to collect customs from the merchants who used the waterways through Berlin-Cölln but most importantly the right to mint their coin, accepted by all the cities of the Mark of Brandenburg. According to the Rostock directory of 1358, Berlin and Cölln had belonged to the Hanseatic League from their very beginning, something that contributed to a great extent to their prosperity.

The merchants and towns federation allowed far-reaching trade relations. Although Berlin-Cölln carried little weight in the alliance, trade with the Baltic Sea region expanded greatly because it became safer for Berlin’s merchants. The main commercial products of the city were mainly rye for the grain shortage areas in the west and north, Brandenburg oak for shipbuilding and town planning, as well as the manufacture of beer and herring barrels. In addition, wool, beer, potash, wax, and canvas were exported. The import consisted of Flemish cloth, metals, weapons, salt, spices, herring from Scania, other sea fish as well as millstones, whetstones, and woad (blue dye plant).

After the death of the last Saxon Margrave in 1320, the Wittelsbach Emperor Louis IV (1328 – 1347) gave Brandenburg to his son Louis V who was also Duke of Bavaria. In 1351 Louis V gave the Mark to his younger half-brother Louis II (the “Roman”) who succeeded in establishing the Margraves of Brandenburg as prince-electors in 1356. That meant that Brandenburg would henceforth have a vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor and its control had wider implications.

The new German emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg, (r.1355 – 1378) immediately moved to secure the control of Brandenburg by the House of Luxembourg and managed to do so by simply buying it from the Wittelsbachs. That affected the affairs of the twin cities which after 1359 were not very active in the Hanseatic League. At the same time, the nobility which ruled the city council and had become wealthy through fiefdoms did not want to comply with the request of the craftsmen’s guilds to participate in the council.

The dispute led to internal unrest in the city, especially after two great fires in 1376 and 1380 when the lower classes (including craftsmen who were not organized in guilds) could not raise the high sums of money decided by the council for the reconstruction. The people had had enough and so appealed to the Emperor for assistance. He, in turn, appointed Friedrich V von Hohenzollern as their special protector. The House of Hohenzollern would rule Brandenburg until WorWarord I – for almost five hundred years.