Early Adulthood

We could say that the stage of Early Adulthood for Bologna began early on, definitely earlier than in other European cities. The resonance of the Studium of law was such that, already in the 12th and 13th centuries, the Bolognese university system was divided into two separate universities: The Citramontani, made up of the four nations of Lombards, Tuscans, Romans, and Campanians; the other of the Ultramontani, which grouped thirteen European nations. In the struggles between the empire and the popes, the city finally took part in the latter.

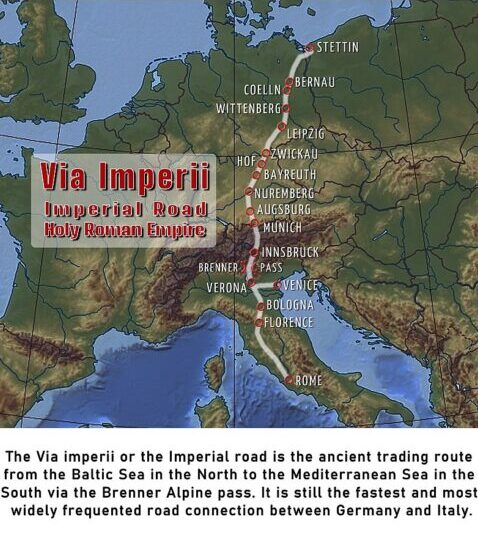

Being on the side of the pope enabled Bologna to assert its autonomy, something that was officially accepted by Emperor Henry V in 1122, a year of reconciliation between the two institutions. Bologna was at the time governed by city consuls. When Frederick I (Barbarossa) became Emperor in 1155 things changed.

The city consuls were sidelined and the ones who governed Bologna were the podestas, who were mostly foreigners who did not feel they had to answer to citizens. The ambitious young emperor wanted to restore the powers of the Holy Roman Empire to what the world had known at the time of Charlemagne. These ambitions would bring him at odds with the municipalities of Northern Italy who were not happy with the extensive powers of the Imperial magistrates.

Bologna was among the first (1167) to join the Lombard League a military alliance of defense against the Emperor. From the accession of Frederick II, Bologna was split into the two factions of Guelphs and Ghibellines, the former being in the majority. In 1184 the cathedral of the city (on the present Via Indipendenza) which had been destroyed in a devastating fire in 1141, is reconstructed and consecrated by Pope Lucius III. In the year 1200, the Palazzo del Podestà is erected on the Piazza Maggiore, facing the Basilica of San Petronio.

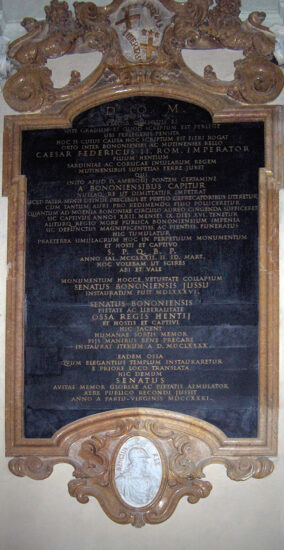

On 26 May 1249, the citizens of Bologna, along with the rest of the Guelph army of the Lombard League would crush the troops of Frederick II in the Battle of Fossalto. The Imperial army of German and Lombard Ghibelline soldiers under the leadership of King Enzo (Ezzelino) although double in size was not even able to protect the king.

Enzo was taken prisoner in Bologna where he was paraded in front of a raving crowd in his full armor and decorated helmet, chained on a horse. Neither the threats nor the promises of Frederick II availed to secure his liberty. He remained in captivity his whole life in the Bolognese palace thenceforth named after him, the Palazzo Re Enzo.

The two schools, that of Roman Law and that of Canon Law, united as one institution the university (or Studio) of Bologna, secured the unwavering attention of the two universal powers of the era, the Empire and the Papacy. The city gradually became the legal mediator of their difficult balance. On the other hand, the Municipality could not afford to arouse discontent among its students, who by coming from all over Italy and Europe, attracted even more artisans and merchants to the city, who flocked to meet their daily needs. This of course led to the direct and indirect enrichment of the entire local economy.

The city was well aware of the international prestige it was obtaining precisely by its Studio, for which already in 1118 it had been given the title of “The learned one” which a century later it would evolve into “The fat one”. By the beginning of the 13th century, Bologna had grown much more than expected and continued to expand beyond the old wall. The new suburbs could not remain unprotected so in 1206 the new wider circle of walls started with the digging of a new pit but it would last decades until the year 1300.

The third and last wall was of course the largest (7.6 km long) and was protected by a moat on the outside. Out of the twelve gates, nine remain to this day. A major earthquake struck Bologna on Christmas Day, 1222, causing the collapse of the cathedral ceiling while another severe earthquake occurred on 21 April 1223, centered at Cremona; and a third centered in Bologna in 1229.

The constitution of the Municipality marked the beginning of a period of great flourishing for the city, which thanks to the university and the freedoms enjoyed by the Municipality reached its heyday in the 13th century. In 1255 the Captain of the People was first introduced. Just as the mayor oversaw the society of the nobles, so the captain of the people oversees the society of the people. A year later Bologna becomes the first European city to abolish serfdom, in 1256. At the time the city became one of the ten most populous centers in Europe, with an urban development equal to that of Paris.

The dominant power in the region of Romagna which included several other important urban centers like Modena, Parma, and Ferrara, the city becomes a Guelph power center, receiving many exiles from the cities where the supporters of the Emperor seize power while sending in the same time many Bolognese to serve as podestas in cities like Ravenna and Imola.

Bologna’s economic wealth was increasingly linked to the textile industry (the art of wool). Equipped with one of the most advanced hydraulic energy supply systems in the world, in the following centuries the city specialized in the manufacture of silk: the ‘Bolognese’ silk mills were one of the most advanced discoveries of European technology up to the seventeenth century.

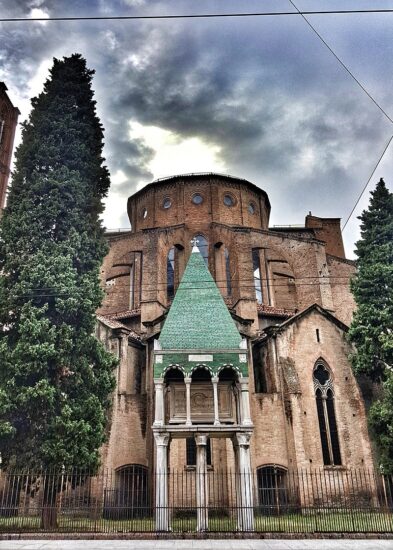

The second half of the 13th century saw the rise of two new basilicas that belonged to the new monastic orders that had taken root in the city at the start of the century, the Dominicans and the Franciscans. The Basilica of San Domenico was consecrated by Pope Innocent IV in 1251. In 1267 the remains of Saint Dominic were placed into the new shrine, decorated by Nicola Pisano.

Work would continue on this shrine for almost five centuries. The Basilica of San Francesco was completed in 1263 less than fifty years after the visit of the founder of the order himself (St. Francis of Assisi), who had visited the city in 1222 to preach to the people of the city sparking great interest in the Order he had founded.

In 1276, to secure greater communal liberty, the citizens of Bologna placed themselves under the protection of the Holy See and Pope Nicholas III sent his nephew, Berotoldo Orsini to serve as his delegate with the task of reconciling the opposing factions. In the years that followed, the powers of the Italian municipalities waned and the republican forms of government degenerated in almost all the city-states which shifted to noble lordships and oligarchy.

In the fourteenth century, the preponderance of power was in the hands of the Pepoli family but in 1350 Giovanni and Giacomo Pepoli sold the city to the Archbishop of Milan Matteo Visconti. After ten years, however, Bologna returned to the papal dominion with the Bentivoglio family holding the reins of power.

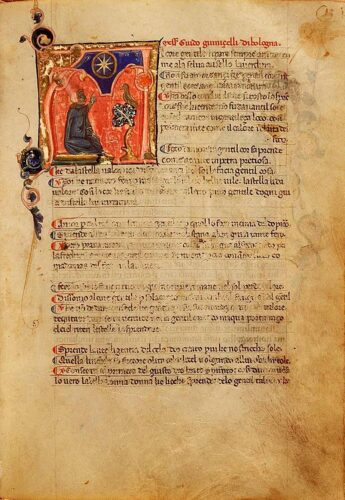

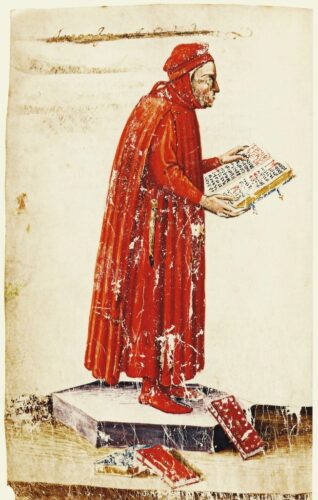

From the 14th century, alongside the schools of jurists, those of the ‘liberal arts’ also flourished: medicine, philosophy, arithmetic, astronomy, logic, rhetoric, and grammar. In Bologna studied, among others the Bolognese poet Guido Guinizzelli, Dante Alighieri who admired Guinizzelli and his compositions, Petrarch and Coluccio Salutati. Its fame attracted numerous and illustrious personalities over the centuries: from the scholar Pico della Mirandola to the humanist and architect Leon Battista Alberti, from Copernicus to the physician and natural scientist Paracelsus.