Grown Up

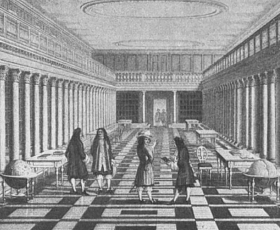

Christian IV’s son and heir Frederick III assumed his position as king at the end of 1648. A great book enthusiast and collector, Frederick established Copenhagen Royal Library during the first days of his reign. He made his life’s work the integration of private collections, manuscripts, and new books that formed the basis of the new institution. With the help of his trusted librarian Peder Schumacher who scoured major European cities for new acquisitions, the collection had reached 20.000 volumes by the time of his death in 1670.

Of course, Frederick III knew that for his reign to be remembered it would take more than a library. He had pretty big shoes to fill. In 1657, under the strain of a constantly growing Swedish dominance Frederick decides to throw down the glove in the hope that he would succeed where his father had failed. He too would fail and Denmark would lose all lands east of Copenhagen with the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658 which placed the Danish capital on the edge of the realm instead of its center for the first time in history.

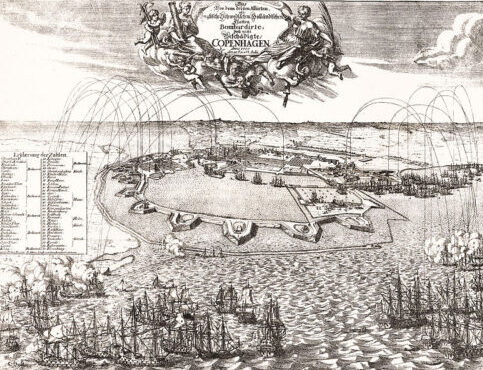

Victory whetted the Swedish appetite, a new round of warfare followed and soon Havners found themselves besieged in their city (1659). With the king actively leading the defense of the capital, the Danes managed to withstand a six-month siege and repel a crucial final assault.

The kingdom was saved and the king’s popularity soared. Frederick III cashed in that popularity swiftly by converting his reign into an absolute monarchy instead of an elective one. He received the title in a celebratory ceremony witnessed by his fellow citizens in front of Copenhagen castle on 18 October 1660.

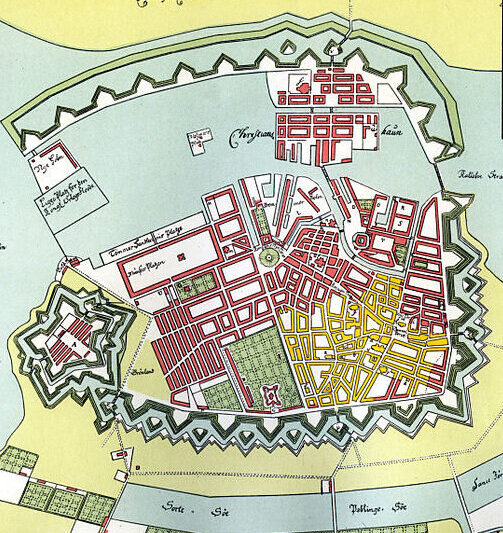

After 1660 Copenhagen was reasserted as the capital of Denmark and Norway. With the growing administrative and military institutions of the state being concentrated in Copenhagen, the city had reached 42,000 inhabitants, by 1672, a population ten times higher than the kingdom’s second-largest city, Aalborg.

The city’s defense was reinforced by the completion in 1664 of Kastellet, which housed 2000 soldiers along with their wives and children, and the addition, (1685-92) of the great bastion series around Christianshavn, known today as Christianshavns Vold. At the same time for Slotsholmen (where the first Absalon Castle later Christiansborg Palace was located) to be better protected Frederiksholms Kanal was created in 1681.

Over-centralized governing did not leave any space for individual municipal policies so all eyes were on the 28-year-old Frederick IV who ascended to the throne right at the turn of the new century. Despite the auspicious credentials of the new king the first signs of the 18th century were anything but. In the summer of 1700, in one of the first acts of the Great Northern War, a joint English-Dutch-Swedish fleet bombarded Copenhagen for six days, between 20–26 July. Although the damage and the casualties were not extensive the attack forced Frederick to withdraw from the war.

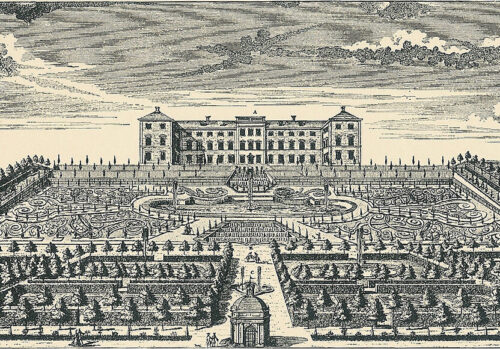

Well-schooled and well-traveled Frederick IV sought to introduce the architectural fad of his days in the capital, particularly the style of Italian Baroque he had grown so fond of in his Italian trips, with the construction of Frederiksberg Palace and its impressive gardens already in place by 1700. The greatest part of the Baroque palace was ready by 1710.

In 1711 a nightmare from the past came again with a vengeance. The dark cloud of the plague stayed over Copenhagen for about a year (June 1711 to March 1712) wiping off 1/3 of the city’s population (more than 20.000 people).

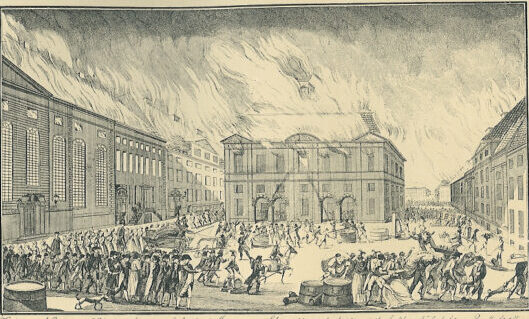

The capital had barely recovered from the shock when another devastation struck. A small fire that broke out in the evening of October 20, 1728, near the town hall square, spread furiously through the wooden edifices of the medieval city, burning down thousands of houses, Vor Frue Cathedral, a great part of the university library, important archives and cultural treasures. An estimated 20% of the population became homeless and almost 30% of the city was consumed by the raging fire that lasted for three whole days.

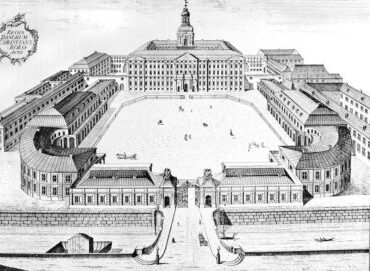

The great task of the reconstruction was taken on by Christian VI who showed all the impetus of a new king starting from his inauguration year (1731) with the demolition of the outdated Copenhagen Castle to make way for Christiansborg Palace, the building of Hermitage Hunting Lodge in Dyrehaven three years later and the Rococo Prinsens Palæ Prince’s Mansion a bit later on. All of the damage by the destructive fire had been repaired by the end of his term in 1746.

European fashions continued to change and so did kings. Frederick V took over in 1746 and his term would be mostly characterized by the Rococo style. In 1748 the Royal Danish Theater on Kongens Nytorv is inaugurated and the plans for Frederiksstaden, a sumptuous complex commemorating the 300 years jubilee of the House of Oldenburg are laid out.

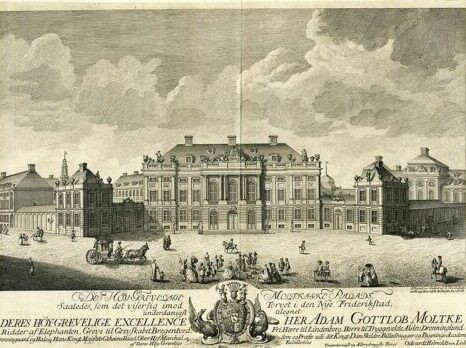

Works start a year later with the foundation stone for the imposing Frederik’s Church being set by king Frederick V on October 31, 1749. The prominent district at the waterfront was destined to house noble families and wealthy merchants of Copenhagen but would soon pass into the hands of the Royal family (it would evolve into Amalienborg Palace when Christiansborg Palace was destroyed by a fire in 1794).

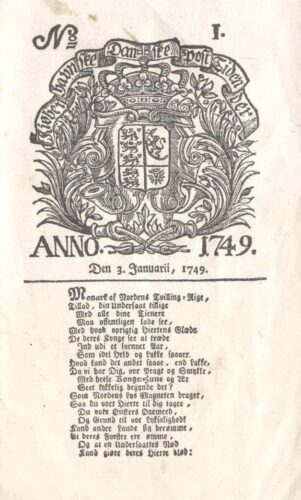

At the beginning of 1749 the first issue of Copenhagen’s Danish Post-Times, the first Danish newspaper is published. In the same year, the construction of the impressive spiral tower of Vor Frelsers Kirke (Our Savior Church) begins. Holmen naval base is modernized with the addition of Mastekranen, the first piece of industrial equipment of that scale in Copenhagen.

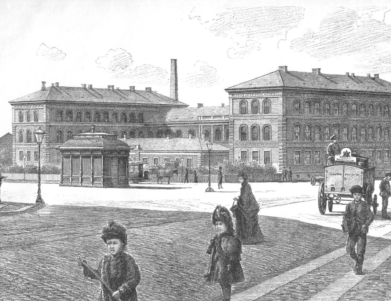

In 1752 Frederiks Hospital, Denmark’s first organized hospital is founded and the adjacent Oeder’s Garden was constructed, financed by the earnings of the Norwegian Postal Service. The hospital would be fully operative by 1757 while the Garden was opened to the public in 1763.

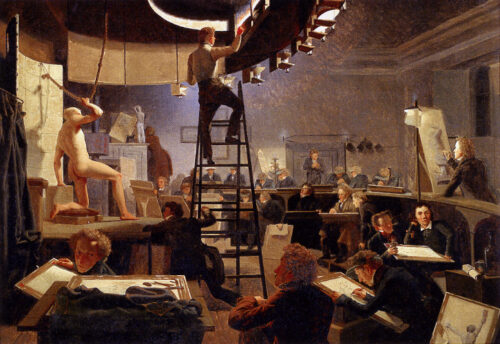

In 1754 the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts is founded and four years later Amalienborg and Frederiks Church are completed. In 1766 the greatest builder of Copenhagen after Christian IV was interred in Roskilde Cathedral. His equestrian statue, placed in 1771 at the center of the octagonal square of Frederiksstaden would cost more than the four palaces of Amalienborg combined.

Between 1770 and 1800 Copenhagen experienced a sharp economic growth that became known as the Florissante period (the blossoming period). At the time major wars raged throughout the European and American continents. The fact that the Danish kingdom managed to stay neutral and abstain from the wars gave its merchant fleet the chance to take over the trade routes of the warring nations.

With Copenhagen being the safest and most organized of all the Danish ports, the city’s economy boomed. Money circulated faster than ever, traders made more money than ever and more ships entered the Danish merchant fleet by the day. The creation of new industries was promoted with special privileges and new factories producing textiles, porcelain and sugar created new jobs.

A new sophisticated bourgeoisie that had at its disposal newspapers, large mansions, and scientific and scholarly societies emerged. The city’s population exploded from 80.000 in 1770 to 100.000 in 1800.

Right before the beginning of the Napoleonic wars just like a bad omen, two great fires spread destruction in the capital. The first destroyed Christiansborg Palace forcing the royal family to purchase and move into Amalienborg Palace. The second ravaged the western part of the city, burning down 1/4 of the city and turning 3.500 people into homeless.

The British Empire’s strong suit in the battle with Napoleon was its mighty navy. Having a strong fleet that could supply the French with everything needed under the blanket of neutrality was not something that could be tolerated by the Brits. In March 1801 a fleet of about forty British ships sets sail for Copenhagen.

Although the Danish fleet was caught off guard and the naval defense of the capital was partly manned by volunteers on April 2, 1801, the capital would manage to go through the Battle of Copenhagen, unscathed, despite the heavy losses in men and ships. Copenhagen’s firepower proved to be stronger than expected for the English who also suffered many losses.

History would not repeat itself six years later when the Brits came back again. With Napoleon’s navy being obliterated at Trafalgar in 1805, the British feared that the French would make use of the Danish ships to invade Britain. An ultimatum for the surrender of their fleet could not be accepted by the Danes.

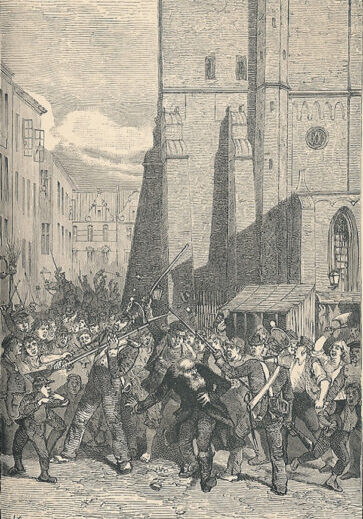

The first battle between the two armies was won by the English (Battle of Køge – August 29, 1807) who then laid a siege to the Danish capital. Between the 16th of August and the 5th of September 1807, Copenhagen was viciously battered with constant bombardment in one of the first blind attacks against both soldiers and civilians in modern history. The use of special incendiary bombs that could not be extinguished by the British military had devastating effects on the city.

Almost all of the wooden structures that had been spared from the previous fires were burnt to the ground along with the recently rebuilt Cathedral of Vor Frue Kirke). 1600 Danes died and 1600 more were wounded. On 7 September 1807, the city’s appointed commander Ernst Peymann surrendered the capital and the fleet to the English who took over most of the Danish ships and destroyed the rest. By the end of October, the British had fled Copenhagen with the entire Danish Navy. 80 warships and 243 transport vessels.

Without its merchant fleet and the warships protecting it, the Danish economy struggled to cope with the wake of the attack. To make matters worse the kingdom had sided with Napoleon after the attack on Copenhagen, so when the French were utterly defeated, the state was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1813 and cede Norway to Sweden in 1814 after 450 years of a joint kingdom between the two.

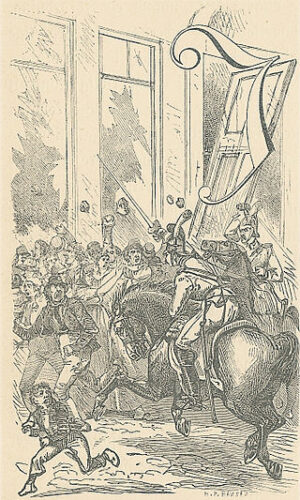

The economic depression created dissatisfaction, criticism, and protests. King Frederick VI‘s fears of a revolt led to a more autocratic regime marked by censorship and suppression. The growing need for decompression found a way out in one of history’s most common scapegoats. The pogrom against the city’s Jews lasted from September 3rd, 1819 to January 1820. About 40 people were sentenced by the city’s courts in the following months of the unrest.

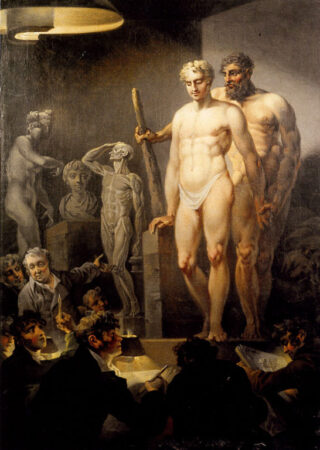

Despite the economic woes and political unrest of the era, sciences, art, and culture seemed to have a momentum of their own. Cultivated by the teachings of talented and traveled painters like Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg and Christian August Lorentzen who initiated their students in the European trends, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen became a fruitful field that produced an array of exceptional painters and sculptors in the first half of the 1800s.

The Royal Danish Theater also flourished based on its ballet performances orchestrated by the renowned August Bournonville (1805-1879) whose clearly defined style and unique training techniques are still being performed to this day. With his help, the Royal Danish Ballet became a ballet institution unmatched by any other company in the 19th century.

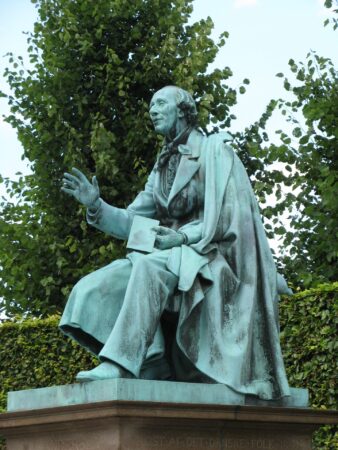

A fervent admirer of the theater, the 14-year-old Hans Christian Andersen came to Copenhagen right amid the Anti-Jewish riots with the ambition to work in the Royal Theater as an actor, singer, and ballet dancer. He soon began writing his first plays that were however deemed unsuitable for performing on stage. He would later become the most prolific and well-known author and poet in Denmark’s history immortalized by his world-famous fairy tales like The Little Mermaid, The Ugly Duckling, and The Emperor’s New Clothes.

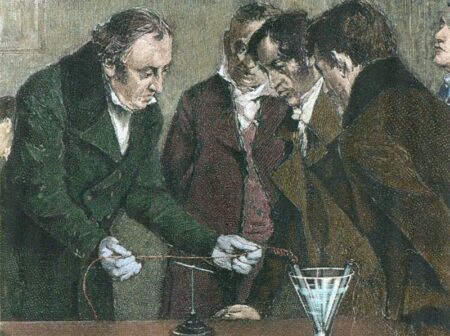

A close friend of Hans Christian Andersen was a prominent man of science that contributed a great part to the addition of science in the so-called Danish Golden Age. Hans Christian Ørsted was a physicist and chemist who discovered electromagnetism in 1820.

Ørsted founded the Polytekniske Læreanstalt (College of Advanced Technology) in Copenhagen in 1829 with the first MSc program in Engineering at a high academic level – to make use of scientific progress in the service of society by applying technology. He was also the founder of the Danish Meteorological Institute and the Danish Patent and Trademark Office.