Grown Up

The Russian Era started with Tallinn trying to stand on its feet, not so much because of the change in power, or the damage in its structure. The largest change occurred in the human capital, with the city experiencing the loss of more than half of its total population mostly due to the plague. In 1714 Tsar Peter I of Russia acquired a humble little manor house (today Museum – House of Peter the Great) and used it as his residence during his first visits. He particularly liked the view of the sea and the harbor from Lasnamägi Hill behind the manor. It made it possible to observe the hostile vessels that patrolled the Gulf of Finland due to the ongoing Great Northern War (1700-1721). Four years later he acquired the lands surrounding the manor and started building Kadriorg Palace and the park ensemble in honor of his wife Catherine I of Russia. The Tsar’s first place of residence in the park became known as the old palace. That first Russian addition to the city’s landscape followed the popular Baroque style of the era, a style the Tsar had introduced to Russia following his visits to France, a few years earlier.

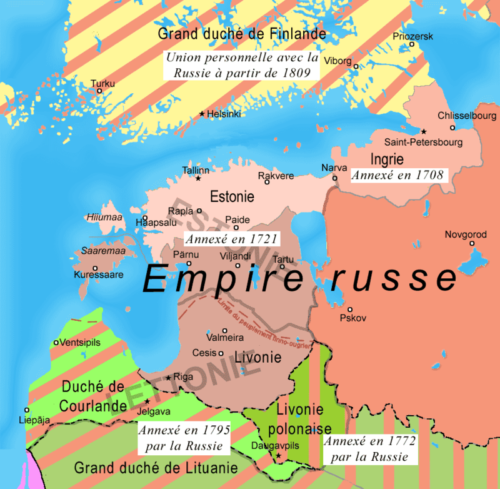

After the Treaty of Nystad in 1721 the territories conquered by the Russians in the Great Northern War were organised in the Reval Governorate, with Tallinn as the capital. Towards the end of the century it would be renamed as the Governorate of Estonia. Contrary to what one would believe there was no Russian elite that came to Tallinn to take the city’s helm. The people of German origin, that had never stopped being the majority of the population in Tallinn were restored to their ancestral privileges as the ruling elite. That made their relation with the Russian Court even smoother than the one to the people of Estonian origin. A new military port was constructed and new naval enterprises were founded. The population quickly bounced back. Tallinn started thriving again.

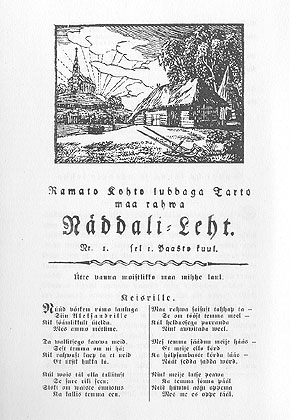

In the second half of the 18th century, a group of educated upper class Germans with time in their hands delved into the native Estonian culture and started promoting the native language, romanticized its traditions and local folklore. Following the values of the Enlightenment, they founded scientific societies, published school texts, books and newspapers, created national epic tales like the Kalevipoeg. The Bible was translated in Estonian and the number of books and brochures published in Estonian increased from about 15 in the 1750′ s to more than 50 in the 1790’s. The movement, known as Estophilia would continue well into the 19th century and would lead to the Estonian national awakening of the 1850’s.

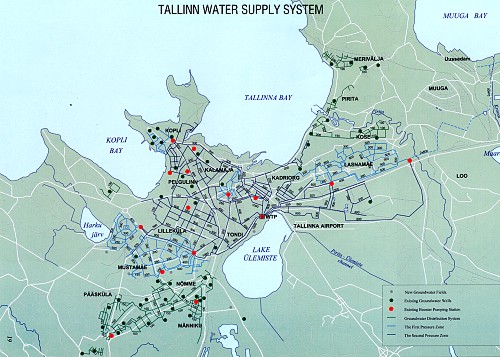

In the first half of the 19th century, a paper mill, a tea factory and a machinery factory were established. The population of the capital went from 6,950 people in 1772 to 12,000 in 1816, to 24,000 in 1850. The abrupt increase of the population in such a small period created sanitary problems. The sanitary problems created epidemics. The cholera hit Tallinn first in 1831 and again in 1848, taking the lives of nearly 2,000 people. The urgent renovation of Tallinn’s infrastructure wouldn’t be over until 1885 when a new main pipeline running from Lake Ülemiste to Raekoja plats (Town Hall Square) and from there to all the streets of the Old Town. The Toompea sewerage plan followed suit.

In 1870, the new Baltic Railway (Balti jaam) united Tallinn with St. Petersburg and other parts of the Russian Tsardom, greatly boosting trade links. The machinery industry, the pulp and paper industry developed and a new gas factory was founded. By the end of the 19th century horse drawn Tram had started roaming the streets, the Toompea was administratively united with Reval and the city had broken out of its tight fortress confinement. St. John’s Church and Kaarli Church were built for the Estonian congregations and the Orthodox Nevsky Cathedral as part of the Tsarist Russification policies that were intensified after the unification of Germany in 1871 and the fears of a possible insurgence of the Baltic Germans. Nationality was a concept that was only just beginning to resurface as the old empires started to lose ground to national states and Estonians were being left out of Tallinn’s affairs for too long.