Grown Up

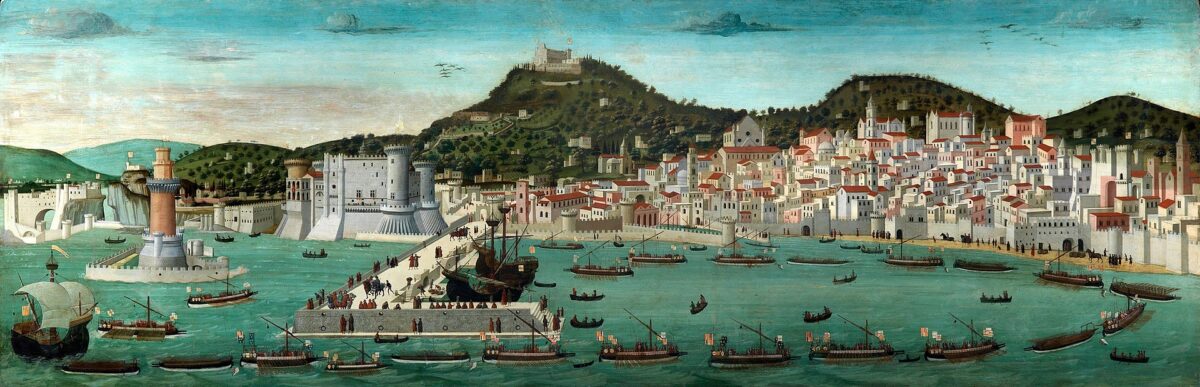

Although Alfonso V was viewed by the people as a foreign leader he did not treat the newly conquered Kingdom of Naples as such. In fact he immediately showed his intention of making Naples his homeland, so much so that from 1443 he resided permanently in Naples, making it his royal seat and leaving his paternal kingdom in Spain to his brother Juan II. All his care and thoughts were directed towards Naples and nearby Sicily, his Regnum Utriusque Siciliæ, meaning “Kingdom of both Sicilies”. The new dynasty enhanced Naples’ commerce by establishing relations with the Iberian peninsula. The population skyrocketed making Napoli the most populous city in Europe after Paris by the end of the 15th century with more than 100,000 residents. Thousands of Jewish refugees expelled from the Iberian peninsula came to the city adding to the hundreds of Greeks who had fled after the fall of Constantinople (1453) making Naples their new home, a trend that continued during the 16th century. Poetry, literature and arts flourished in a cultural hodgepodge that would turn Naples into an epicenter of the Italian Renaissance. Alfonso V would also start the total reconstruction of the Angevin Fortress, fallen into ruin since its completion in the late 1200’s; he paved the streets of the city, cleaned out the swamps and boosted the wool industry that had been introduced by the Angevins.

Alfonso V’s death in 1458 would create fear and uncertainty for the future to Neapolitans but not to its powerful feudal barons who wanted to rid themselves of Alfonso’s illegitimate son, Ferrante who had succeeded him as Ferdinando I. The rival claimants from the House of Anjou and the Spanish brunch of the Crow of Aragon were more than willing to take up the challenge but Ferdinand I would manage to hold on to the crown through real politik and ruthless suppression of the feudal lords. His reformist and firm governance would favor the economy of Naples and especially of small artisans and traders who were liberated by the tight grip of the old cast and were able to flourish through novel technologies like the printing press and silk production. The cathedral which had almost completely collapsed due to the terrible earthquakes in 1456, was reconstructed, a series of magnificent palaces like the Palazzo Sanseverino were erected, a number of monumental gates such as Porta Capuana and Porta Nolana were added to the new walls, the bell towers of the Basilica of San Lorenzo Maggiore and of the Carmelo monastery were completed. By the time of the end of his reign in 1494, Ferdinando I had managed to make Naples the most powerful among the Italian city-states in essence achieving a Neapolitan hegemony that would define every contest in the Italian peninsula at the time.

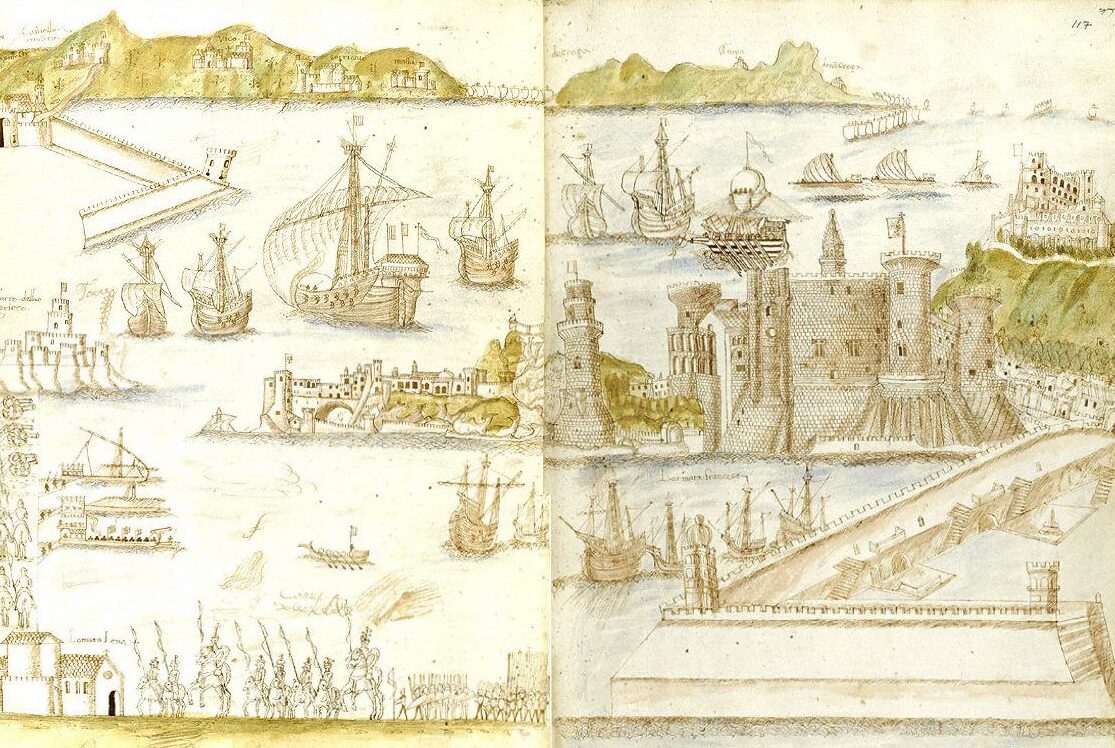

The French who had been entangled in Italian politics for hundreds of years reiterated their interest when Pope Innocent VIII, then being at odds with Ferdinand I of Naples, offered Naples to Charles VIII in 1489. The French king wanted to form a new state in central Italy and control it as the new ruler of Naples. When Ferdinando I died in 1494, Charles invaded Italy. Neapolitans welcomed the French king, especially the nobles who hoped they could take back some of the power they had lost. Milan, Venice, Mantua, and Florence formed a coalition but were convinced that in order for their alliance to succeed, they needed the Spanish king as a counterweight. The perplexed picture would be resolved with an agreement between the two big players and the French re-entered Naples as rulers in 1501. Adherence to the terms of the agreement didn’t last for long, the matter was resolved through war and in 1504 the Spanish troops evicted the French and entered Naples as the new overlords. From now on Naples would belong to the vast Spanish Empire.

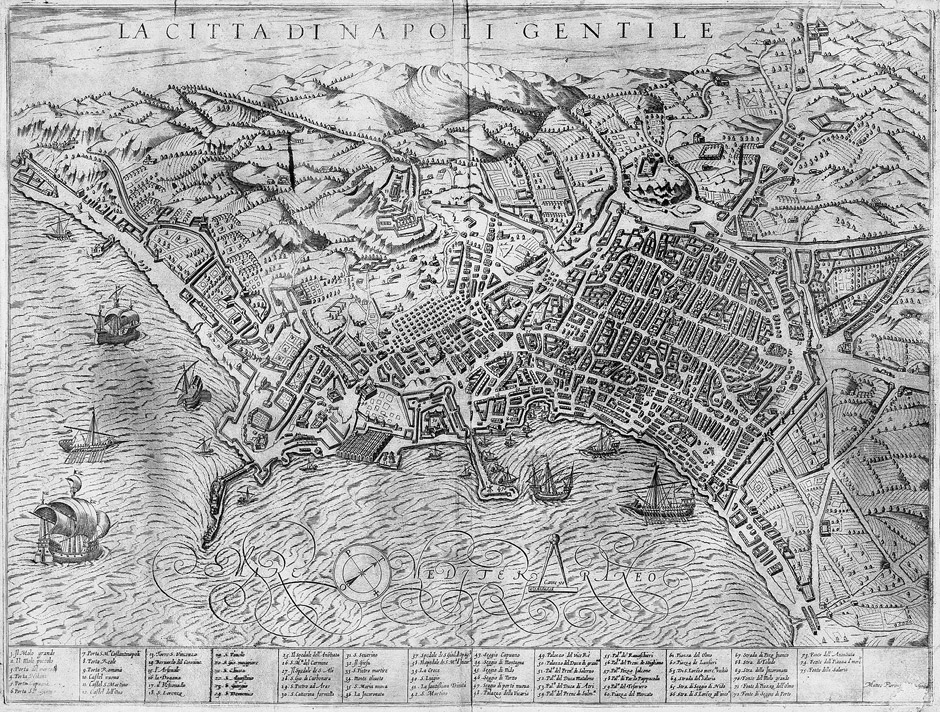

The Spanish crown exercised its power over Naples and the kingdom with greed and ineptitude. A series of viceroys (more than forty) became the protagonists of oppression, theft of works of art, imposition of strangling taxes. It was during this period that the phenomenon of the Camorra was born and affirmed itself. In that early stage the Camorra was actually a sort of secret society with the purpose of mutual assistance to defend the people from Iberian bullying. Numerous war events marked this era while on the home front, there were numerous attempts at popular uprising, due to the unsustainable tax burden and the attempts to establish the Inquisition. The most famous and daring was that of 1647, with Masaniello a fisherman from Amalfi, at the head of an angry mob, which kept the Spanish “masters” in check for over a year, until the capture of the Castello del Carmine, the headquarters of the insurgents. The most noteworthy additions to the city-scape from that period were the Palazzo Reale di Napoli, completed by 1620, the Certosa di San Martino monastery reconstructed in 1623 and the Jesuit Church of Gesù Nuovo built by 1601. In 1656 a major outbreak of the plague would claim the lives of more than half of the total population (150,000–200,000 people).

The expansion of San Gennaro dei Poveri hospital and the inauguration of the new dock for the city’s arsenal in 1668, were not enough to disguise the general decline of the Spanish Empire that dragged Naples with it. The devastating blow of the plague was too severe for Naples to bounce back quickly. Even law enforcement during the latter part of the 17th century seemed impossible. The death of the King of Spain, Charles II 1706, with no apparent heir opened up the so-called War of the Spanish succession which evolved into a prelude of a world war with Austrians, British and Portuguese on one side and French and Spanish on the other. The nobles of Naples tried to take advantage of the situation and rid themselves of the Spanish crown in favour of the Austrians who were eager to take over and sought the endorsement from the Pope. They would march to Naples without it and take the city with no real resistance in 1707.

The Austrian viceroys were stationed in Naples but real power stemmed from Vienna. The Austrians were cultured people and brought with them the age of Baroque, the fad of their time. Art, music and philosophy showed signs of rejuvenation, while the city became a part of the Grand Tour with many north Europeans in a search of the glorious European cultural heritage assisting Neapolitans in their rediscovery of their own Greko-Roman past. The stance of the Vatican in the recent war had not been forgotten so a limit to the increasing number of religious buildings and institutions was set in the city which saw the first planned interventions in its layout after a long time, with the expansion outside the city walls and the carving of coastal roads that led out to the slopes of Vesuvius, roads that would eventually define the modern expansion of Naples in that direction. The Baroque interventions in in the chapels the apse and transepts of the Cathedral and Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1725), the baroque masterpiece by Francesco Solimena that adorns the back of the facade of Gesù Nuovo are the most noteworthy additions to the city’s aesthetics of the Austrian era that would only last until 1734.

The Spanish viewed the Austrian rule of Naples as a nuisance they had to rectify. Naples was theirs for far too long for them to be at ease with the change of its status. In 1733 a new round of war started between Austrians and French. Spain wanted in. Charles III of Spain, the Bourbon heir of the Spanish crown, Duke of Parma and Piacenza had just reached his majority, the needed age to be the commander of all Spanish troops in Italy. Neapolitans again needed a change. The nobles sought for a king that would rule from Naples. Charles III was very likely to be a perfect suit. With the Austrians fighting the French in Lombardy it was the perfect opening for the young prince. The Spanish troops took Procida and Ischia in March on 9 March of 1734. A week later they defeated the Austrians at sea and by the beginning of May they had reconquered Naples. Charles was crowned King of Naples and Sicily in the recently restored Duomo on 10 May 1734. Although his father was King Philip V of Spain, he would rule Naples and Sicily as an independent kingdom, from Palazzo Reale di Napoli, the first ruler of Naples to actually live there, after two centuries of viceroys.

In the 25 years of his reign, Charles managed to create a spectacular architectural legacy for the city. Three palaces, the Palace of Capodimonte (National Gallery today), the Palace of Portici (Museum and Botanic Garden of the University of Naples) and the Royal Palace of Caserta, the largest palace erected in Europe during the 18th century (UNESCO World Heritage Site) and Piazza Dante being the most noteworthy landmarks of his reign. The Farnese book collection of the King that became the base upon the National Library Vittorio Emanuele III was built, the foundation of the National Archaeological Museum, the creation of the National Academy of Fine Arts, one of the oldest in Europe, the building of the oldest opera house in Europe, the Real Teatro di San Carlo and the support to the Neapolitan musical school, the re-descovery and excavations in Herculaneum and Pompeii were only some of his astounding contributions in the city’s cultural heritage. His enlightened governance included a series of reforms in the administration, in the tax system, in trade and military sectors, created a new impetus for economic growth in the following decades in activities that formed many aspects of the economic fabric to this day: from crafts (the processing of coral, ceramics and porcelain, precious metals, wood) to commercial growth (the port of Naples). Strong was also his commitment to contain the temporal power of the clergy and to abolish the feudal privileges still existing at the time. His rule made him a shining example of the humanist intellectual zeitgeist that would form the foundations of modern Europe. The list of his contributions would continue up to the day of his abdication from the throne of Naples in favor of his son Ferdinand I in 1758, a prerequisite for his accession to the Spanish throne.

While following his father’s line of policy, Ferdinand I was a lesser figure from a historical point of view. The birth of early industrial production (Royal shipyards of Castellammare, the silk factory of S. Leucio), the transformation of the Chiaia beach into the Royal Villa, which later became Villa Comunale, the establishment of the military school of the Nunziatella and the colossal public granaries of Granili, can however be attributed to his reign. In 1789 the winds of the French Revolution reached Naples, arousing the horror and disapproval of the Court of Ferdinand, while at the same time in the city the liberal and Jacobin ideas began to spread and dominate the salons of the intellectuals. Conspiracies were followed by repression and in 1794 the death sentences of the first conspirators were carried out. Hostility against the monarchy would reach its peak in 1799, when the Napoleonic general Championnet enters Naples forcing Ferdinand to flee to Sicily. Under the protection of French arms the Neapolitan Jacobins proclaim the establishment of the Parthenopaean Republic.

The king regained control after six months, ending the short-lived dream of the Neapolitan republicans, with hundreds of them executed for treason shortly thereafter. In 1806 however the French would return again entering Naples not as defenders of the republic but as soldiers of the Napoleonic Empire. Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon’s brother) became King of Naples but he would also rule for a short while, before he was succeeded by Joachim Murat (Napoleon’s brother-in-law) in 1808. The new French era shook the foundations of the society of southern Italy. Whatever was left of the old edifice of church and baronial privileges was torn down. The ideals of the French Revolution were infused in the administration and judicial and educational system. Divorce, civil marriage and adoption became legal, new scientific and industrial studies were introduced in the university of Naples, Piazza del Plebiscito and the monumental Church of San Francesco di Paola were built, the Ponte della Sanità was constructed to connect Capodimonte Palace with the rest of the city and the much photographed for its scenic seaside views Via Posillipo was carved out on the edge of the Neapolitan coast. Murat played all his cards in order to keep the throne but the allies weren’t willing to let a figure identified with Napoleon keep his position after the fall of their great enemy. Murat was arrested and executed, while Ferdinand I was restored on the throne as King of Naples and Sicily (Two Sicilies) at the end of 1816.