Maturity

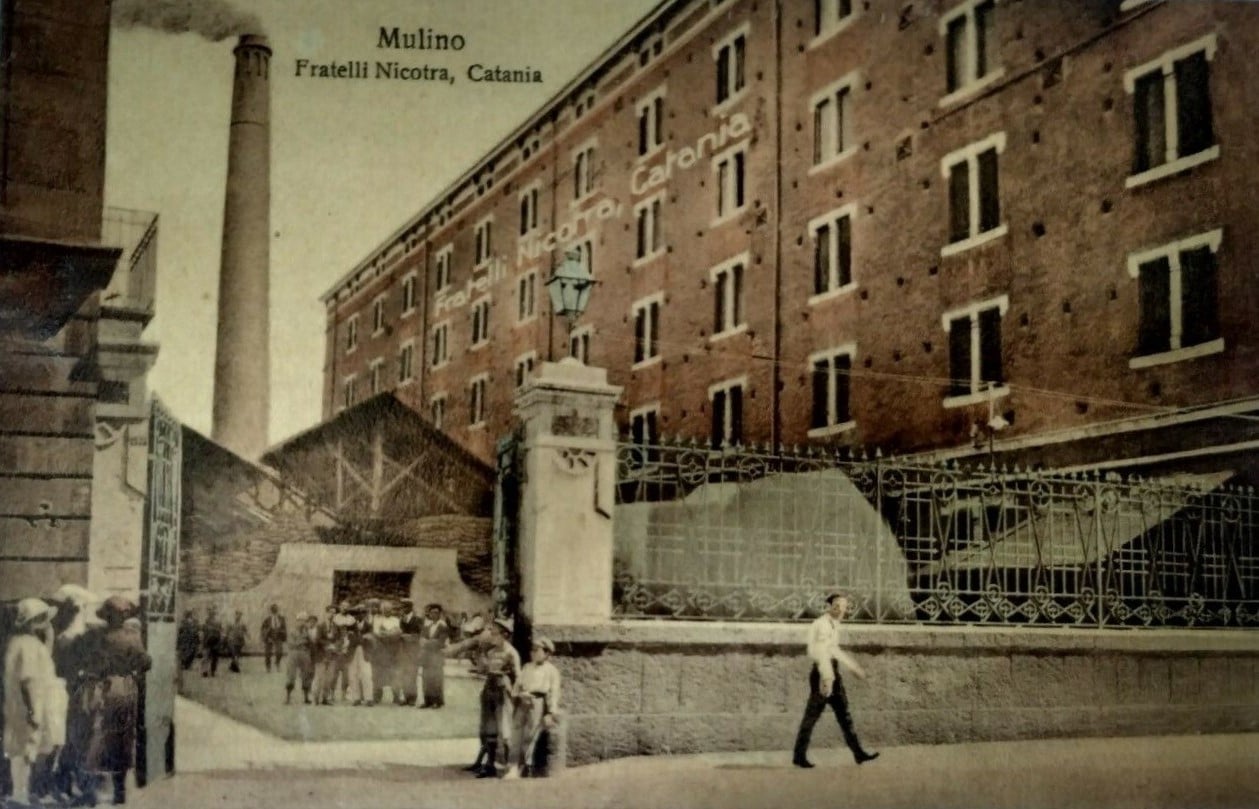

In the early years of the unification of Italy a stratum of radical intellectuals is being formed, among whom republicanism is combined with total confidence in the renewing power of science. The poet of this period is Mario Rapisardi (1844-1912), a poet who bases the palingenetic vision of a renewed humanity on anti-clericalism and the rejection of the present. With the laws of ecclesiastical reform after 1866, the city acquired a large part of those convents, monasteries, and other real estate whose eighteenth-century reconstruction defined the urban center. They will become schools, barracks, public offices: an excessive concentration of functions within a short perimeter, which today, after more than a century, has become unbearable. But it is also a great opportunity to buy, speculate, invest. And it is on these works that the city begins its growth: the Via Stesicorea (Etnea) is fixed, lowering its level; the waters of the Amenano are harnessed (the fountain in Piazza Duomo dates back to 1867); new paths are traced and opened; in 1866 gas lighting was installed. And yet, the cholera epidemic strikes in 1866-67 and again in 1887. With the second half of the century the railway also arrives, and with it the connection with the two goods that will be the foundation of a great expansion: the sulfur of the interior of Sicily and citrus fruits. For both, Catania becomes the hub where the product is processed, packaged, traded and shipped. This opens up new branches of industrial activity and begins to differentiate the proletarian classes: sulfur refineries are growing, which together with the railway, with its characteristic arches on Via Dusmet, represents an iron belt that cuts the city out of the sea. In the last decade of the century, the Circumetnea railway connects Catania with Riposto turning around Etna and represents a vital artery for the transport of goods and agricultural workers.

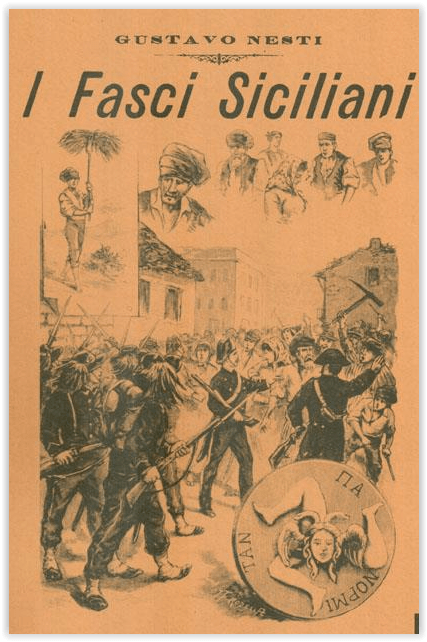

In the years after 1880 there is a period of expansion for Catania, with the city becoming the bearer of a commercial and industrial model for the rest of Sicily. Very active, the young mayor and future foreign minister Antonino Paternò Castello Marquis Di Sangiuliano (1852-1914) focuses on public spending and facilitation of business. A rapid social transformation takes place with the old aristocracy however not showing any intention of giving up the year-long grip of power. The question of social policy becomes the pivot of Catania’s political life: it is inspired by Cardinal Giuseppe Benedetto Dusmet (1818-1894), bishop of Catania since 1866, who pours all his energy into the poorest neighborhoods of the city in a sort of a movement of social-Catholicism. With the agrarian crisis, the visions of the Liberals, Catholics, Socialists collide with each other with the latter gaining a real momentum in Eastern Sicily with the movement of Fasci Siciliani.

In 1890, after thirty years of effort, Catania also has its own Teatro Massimo; some time earlier, carrying home the body of Vincenzo Bellini, the city had began to see herself in her heroes. The city is populated by foreign traders: they are exporters of citrus fruits, entrepreneurs, shopkeepers, who are called Brodbeck, Caflisch, Caviezel, Ritter, Wrzy; Swiss who were responsible for the founding of the Waldensian and Evangelical Churches, and who soon earned a place in the ranks of the local elite. A sign of economic progress the great commercial exhibition of 1907, the inauguration ceremonies, in the presence of the royal family, of the which would visit again during the unveiling of the monument to Umberto I in 1911.

The rising star of the great Catania bourgeoisie is Gabriello Carnazza (1871-1931), from a large Risorgimento family, linked to the financial interests of the new electricity groups, interested in large land reclamation projects. Nationalistic and agrarian factions converge on the right and so will he despite his initial election with the Social Democrats. The city seemed to feel more comfortable in a commercial vesture than an industrial one. With WWI and the subsequent crisis of fascism, the commercial circuits are broken; Sicilian sulfur loses its importance; the city enters into a deep crisis. A large group of lively young people, strongly seduced by futurism and the hope for a better life left Sicily. Between 1901 and 1913 almost a quarter of Sicily’s population departed for America. Nearly 50% went back to Italy after making enough money in the US.

There is no shortage of major projects in this period. There are a lot public works of power and prestige: a new prison, a new courthouse, the rehabilitation through the demolition of the old San Berillo district; some of these projects, interrupted by WW2 war, will not be completed until the 1950’s. During the Second World War, Catania experienced hunger, displacement, bombing, the political crisis of the regime; these things, and especially the heavy bombings of July 1943, left their mark. With the Liberation by the Anglo-Americans there was no stimulus to rebuild a new collective personality: instead came smuggling, banditry, profiteering, the passive acceptance of chaos. In December 1944, the crowd that set fire to the Town Hall did not even disguise under the banner of separatism; it was just a mass tired of war and hunger. A new episode by Antonio Canepa, founder of the Movement for the Independence of Sicily and leader of the separatist guerrillas, killed in 1945, did not produce a significant popular response.

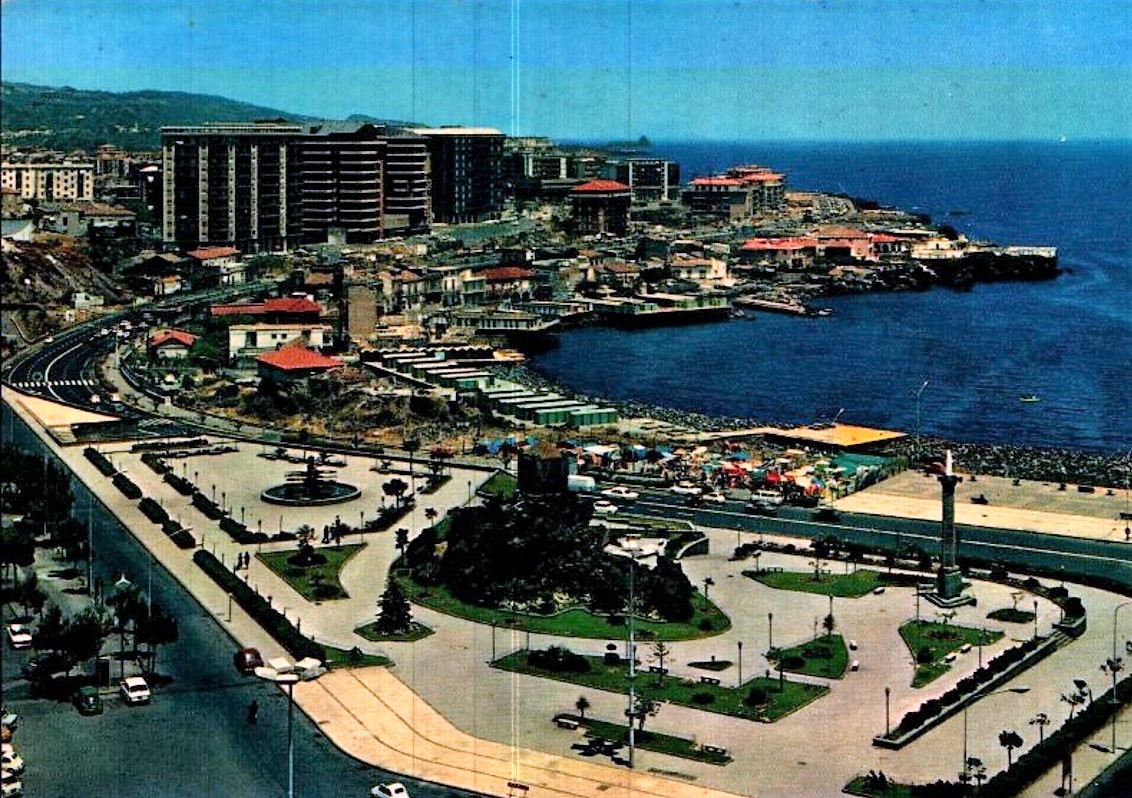

The years of reconstruction showed that the sense of civic conscience was not completely extinguished: it is significant, for example, that the eighteenth-century Palazzo Massa di San Demetrio, in Quattro Canti, destroyed by bombs, was rebuilt exactly as before. Soon the building itself became both the engine and the driving force of economic development. At the turn of the 50’s and 60’s, the spirit of reconstruction and enterprise of the people of Catania is manifested once again. The Pantano d’Arci industrial area is born in the south, large construction companies are formed and developed, trade flourishes. And the myth of Southern Milan returns.

Urban expansion takes place in a contradictory way. Speculation brings to completion the demolition of San Berillo (the gutting of a significant part of the historic center), the Japanese architect Kenzo Tange who is called to draft the master plan, designs a balanced urban development, aimed at enhancing the peripheral districts and the southern area of the city, in order to overcome the monopoly of the old city core. Catania, proves to be a dynamic city, rich in autonomous entrepreneurship, unlike other southern and Sicilian cities, which are overrun by foreign industries that often devastate their region, creating social tensions. In ’68 the young people of Catania take part as protagonists in the student uprisings, an expression of the zeitgeist in the city at the time.

The economic and cultural revival clashed, however, in the 1970s with the new mafia and with the degenerative processes of political power. The transformation, in western Sicily, of the rural mafia first into an urban mafia and then into a financial mafia, extends the area of influence and intervention of the mafia gangs throughout Sicily. Also in Catania a mafia power is formed and organized, in a way that in essence controls civil life, economic activities and politics. Despite this, the city maintains a modern and secular identity, as evidenced by the high percentage of votes, above the national average, in favor of divorce and abortion, in the most significant referendums that took place in that period. In the 1980s a strong democratic reaction took place against the Mafia and against the degenerative processes of politics, which broke old and consolidated balances of power. The political crisis, however, continued until the end of the decade, leaving the city essentially without a guide. The effect of the absence of government is evident by the lack of public works and housing, which had been a driving force for development, the profound crisis of the industrial apparatus, the deterioration of commercial and textile activities in general, the impoverishment of cultural debate.

Only at the beginning of the 1990’s do the first symptoms of a reversal of trend begin to appear, because a new ruling class begins to redesign a project for the future of the city. But progress is slow and contradictory, because the failures of the 1980s have left deep marks and because the negative national economic situation affects the South the most. The main concern of the new ruling class is to guarantee political and administrative rigor, maintaining a civil climate in the political confrontation, at the height of the best secular tradition of the city. While elsewhere the crisis of the 1980s produced deep social and political splits and hatreds in the end a spirit of tolerance prevailed in Catania, which allowed an administration based on constructive democratic procedures and on consent.

The historic center was transformed into a living space, where it is possible to circulate and have fun until the crack of dawn; new cultural and artistic activities flourished; the popular neighborhoods acquired new services and facilities. It is true, however, that the unemployment rate remains very high and that young people are anxious about the future. The main question as in the whole of the South of Italy is the main issue in Catania today. To face it and solve it, it is necessary to carry out the Catania 2000 project, which is already being worked on: modern infrastructures, freight villages, telematic networks, high technology, scientific research, support for businesses, enhancement, also for tourism purposes, of the environmental and historical heritage.

Based on the history by www.comune.catania.it