Real Alcázar

The whole of the Real Alcázar of Seville is the mirror image of the evolution of ancient Roman Hispalis, to Spali of the time of the Goths, of Ixbilia of the High Middle Ages. At the beginning of the 10th century (913), the Caliph of Córdoba Abderrahmán III ordered the erection of a new government precinct, the Dar al-Imara, on the southern flank of the city, according to the most trustworthy testimonies. Before that, the power base of the Umayyad al-Andalus was not far from the Aljama Mosque of Seville (current Cathedral). The most important government building in Seville was already linked to the port of the city, the most important hub of economic activity. The old port of the city, on the grounds of the current Plaza del Triunfo, known as the Esplanade of the Banu Jaldún then, it was following the westward direction of the main course of the Guadalquivir.

To the Umayyad government palace of the 10th century, the Abbasid, the new rulers of Seville and its region later added the New Alcázar. This Palace of al-Mubarak, the Blessed, was already the center of the official and literary life of the city. Later, the Almoravids would extend it further while the Almohads, in the 12th century, would complete the works of the Arab period.

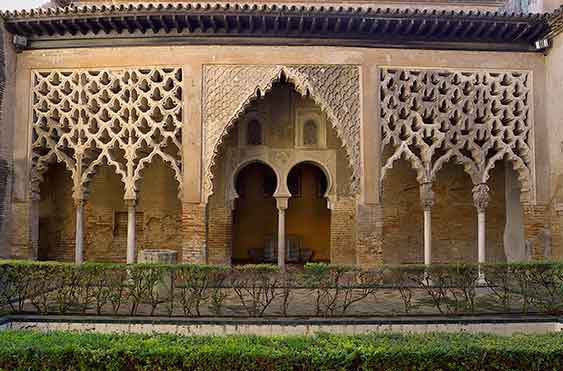

The Castilian conquest of the territory in 1248-49 endowed the Royal Alcázar with the administrative vestige which partly remains to this day: the seat of the Crown and the scope of the municipal power of the city. Based on the pre-existing structures, the new additions were incorporated in a style of integration of cultures that is part of the very essence of Seville to this day. Palaces such as the Gothic, in which Alfonso X captures the gist of the new cultural framework in which the city would flourish. The Mudejar Palace of Pedro I, in the middle of the fourteenth century, transfuses old Mediterranean architectural traditions into an Arabesque pattern that would remain a key distinction of Andalusian style in the future.

In this architectural framework one must add the elements that give life to the Real Alcázar of Seville to this day: the new uses of the spaces, the gardens, the water that appears in every corner, a kind of reference to the Guadalquivir and the groups and people who gave life to buildings and constructions at all times and the ones who populated the space between the Puerta del León and the Puerta de la Alcoba, over the Tagarete stream, hidden today under the terrain that gave birth to the current Royal Alcazar eleven centuries ago. (By Rafael Valencia via www.alcazarsevilla.org)

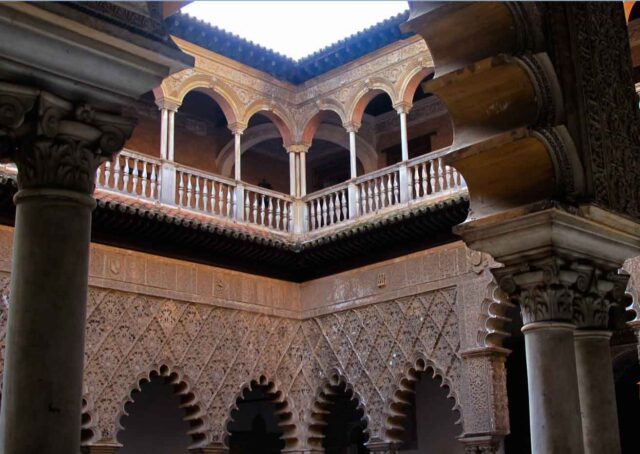

Since the beginning of the Modern Age, the constant connection of the Sevillian Alcázar with the crown of Spain is evidenced in continuous transformations of the building that tried to accommodate its interior to the taste of the new times. Thus, the upper floor of the Patio de las Doncellas was renovated, which acquired a Renaissance appearance of Italian taste. Its plasterwork was also renewed and the arches of the lower gallery were modified. Likewise, splendid coffered ceilings were built throughout the 16th century that still maintained the Mudejar aesthetic and that does not betray the original spirit of the building.

Among these coffered ceilings, the one that covers the wide space of the Ambassadors Room stands out. Other areas of the Alcázar had worse luck, such as the unfortunate transformation process of the delightful Patio de las Muñecas, which has been greatly modified by 19th-century restorations that made its original charm disappear. However, the old columns and capitals were preserved, which retain part of the original imprint of the courtyard.

Magnificent Renaissance contributions enriched the artistic heritage of the Sevillian Alcázar, such as the admirable tile altar made in 1504 by Francisco Niculoso Pisano and which is in the oratory of the Catholic Monarchs or the pictorial altarpiece that is preserved in the Admiral’s Room, dedicated to the Virgin of the Navigators. This altarpiece comes from the Casa de Contratación and was made by Alejo Fernández in 1536.

The Renaissance splendor also shines in the so-called Salones de Carlos V, which are preceded by a monumental entrance made by the architect van der Borch after the earthquake that Seville suffered in 1755. In this portico, the classicist taste that succeeded aesthetics is already reflected in Baroque from the middle of the 18th century. In the interior rooms, there are magnificent collections of tapestries that narrate the conquest of Tunis by Charles V and that were made in the 18th century following the Flemish taste. These tapestries fit perfectly on excellent tiled baseboards made by Cristóbal de Augusta in the mid-16th century.

The Bourbon monarchs, in the 19th century, also left a strong mark on the Alcázar, accommodating spaces on the upper floor of the building, where old rooms were renovated and enhanced by 19th-century decorations with tapestries, crystal lamps from the Farm, clocks, furniture and a remarkable collection of paintings.

Finally, it is necessary to point out the important transformation of the gardens from the Renaissance with the creation of new fountains and ponds, pavilions, doorways, and galleries. The flowerbeds have been permanently remodeled and, until the middle of the 19th century, improved with important innovations that make this landscaped environment one of the most beautiful and beautiful spaces in Spain. (By Enrique Valdivieso www.alcazarsevilla.org)