Maturity

The consequences of economic stagnation that came after 1844 were dire for Berlin: a quarter of the population was thrown into poverty. By 1848 the demand for liberal reforms, national unity, and democratic representation had reached to a boiling point all over Europe. The German Republic movement had even adopted its flag, today’s German flag of black, red, and gold. Demonstrations in Vienna had led the Austrian Iron Chancellor to resign.

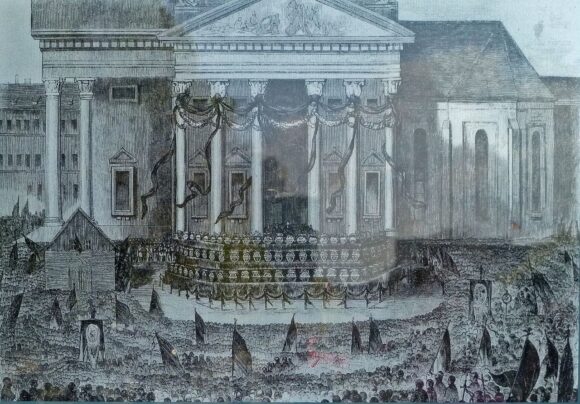

The time for Prussia to rise too had come. The hungry, the working, and the middle class gathered in Berlin to present their demands to king Frederick William IV of Prussia in March 1848. The Prussian Army was called in and soon things got out of hand with hundreds of revolutionaries lying dead in the streets of Berlin. Thousands accompanied the fallen to their burial place. The king was cornered. The new Landtag of Prussia would be the new representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia, governed under a new constitution. A few months later the assembly would be dissolved by royal decree.

Despite the political turmoil, the growing city had become a magnet for immigrants. The population of Berlin including the adjacent settlement areas grew to over 400,000. Care for the poor took up 40 percent of the city’s budget. Wilhelm I (1861 – 1888) who had become extremely unpopular during the riots because of his use of cannons ascended to the throne in 1861. A few months later he appointed Otto von Bismarck to the office of Minister President to implement his plans that would secure Prussia’s supremacy in the German-speaking area.

Bismarck’s goal was the establishment of a unified German state under Prussian rule. In 1869 the new (today’s) Berlin City Hall is completed. Because of its red brick architecture, it will soon be called the “Red City Hall”. Wilhelm I’s and Bismark’s dreams were achieved with the founding of the German empire on January 18, 1871, after the joint victory of the German states in the Franco-Prussian War. Berlin became the German capital and Wilhelm I was the German emperor.

Homogeneity in political, economic, and religious matters became of the highest priority for the new era as was the prevention of a new war with France in the field of foreign policy. To a great extent, Bismark succeeded in his goals something that would vest him in admiration in the German-speaking world. Emperor Wilhelm, I took on the role of the second fiddle, something that he would openly admit without any hesitation, acknowledging his chancellor’s gift for effective governance.

Both Germany and Berlin were electrified and industrialized at a breakneck pace, dozens of new railway stations were inaugurated from 1870 to 1890. The Technical University of Berlin opened its doors in 1879 while in 1884 the foundation stone of the new Reichstag building was laid on the east side of the Königsplatz (Platz der Republik today). The Reichstag’s four corner towers represented the four German kingdoms at unification, Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg. Above all, the 75-meter-high dome made of iron and glass, which was often ridiculed as the “pimple hood” or “cheese bell”, was met with a lot of criticism.

Bismark’s chancellery lasted until 1890. The new king, Wilhelm II (1888 – 1918), with all the impetus of his young age (29 years old at the time of his ascension to the throne) was eager to prove himself and grow his empire. He wasn’t willing to play second fiddle. The new monarchy did not steer the empire away from authoritative conservative militarism of course. On the contrary. Yet many in the middle class had only a very limited interest in the decisions reached in the Reichstag, in part because the freely elected parliament hardly had the power to make real decisions.

Far more important than politics, and certainly more exciting, were entertainment and consumption. Berliners went to the theater and opera shows. They marveled at the first movies, went out to cafés with dancing, to card-playing clubs, and amusement parks. Telegraph lines connected the capital with the rest of the German cities and many of the surrounding countries. A new underground sewage system turned what was to 1871, one of the dirtiest and most foul-smelling cities in Europe into the cleanest large city of the continent by the year 1900. By then the population of the capital had reached one and a half million.

The breathtaking velocity of its transformation had turned Athens on the Spree into a Chicago of Europe, a city its residents were proud to describe as the most American city in Europe. Asphalt paving, an enormous network of tram lines, and all the comforts modern technology could produce were available to Berliners. There were more than 15,000 people with telephones in Berlin.

Major industrial companies such as Siemens & Halske, AEG, and Borsig moved from the city’s center toward its outskirts, seeking space for their enormous factories. It was a city in flux. Its speed and restlessness made the older generations uneasy. One lovely little old house after another was torn down and entire old neighborhoods were taken away from them. They watched resentfully as these up-and-comers who were unconcerned with tradition, and many of whom were Jewish, gained standing in Berlin society, while at the same time the new middle class feared losing its social status. Strains of anti-Semitism and anti-modernism crept into society. (https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/the-late-19th-century-saw-the-birth-of-modern-berlin-a-866321.html).

By 1900 the state and the Protestant Church were one. Wilhelm II wanted a new cathedral that would radiate his empire’s growing prestige and ambitions. A Protestant counterweight to St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

The Imperial state with its immense treasury took over the expenses and in 1905 the grand new Berliner Dom in Neo-Renaissance and Baroque Revival styles was inaugurated. It was a building that would satisfy traditionalists but would not reveal or express the modernist movements in art (Berlin Secession) or the new socialist ideas that were gaining an increasing number of followers in politics.

The population within the city limits exceeded the two million mark and after the year 1911 as a result of the ” Zweckverbandsgesetz (Administrative Union Law) for Greater Berlin” the administrative union of the German capital consisted of an area of some 3,500 square kilometers (1,350 miles²) and 4.2 million inhabitants. Berlin entered the First World War full of confidence.

The First World War did not affect Berlin until relatively late when there were famines and strikes in 1916 and 1917. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated after the German defeat and the revolution of 1918. On November 9 of the same year, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the first German republic from the balcony of the Reichstag.

The so-called Weimar Republic was fragile. Although the allies of the German Empire had collapsed militarily and its army was in retreat before the official end of the war, there was a feeling, especially among former soldiers and right-wing advocates that surrender came before defeat. Huge reparation burdens that had to be paid to the winners of the war crippled the republic’s financial prospects. And then there were radicals on both extremes of the political pendulum that contested in sabotaging every prospect of progress. Consent was unreachable even among the Socialists themselves.

The Republic was identified with a humiliating capitulation and its enemies increased even among the people who had to endure one crisis after another in the 1920s. Prussia and Berlin were SPD strongholds. A brief economic recovery after 1924 based on industrial production gave rise to social housing construction and the New Building movement, which would create Berlin’s six UNESCO World Heritage housing estates, an outstanding example of Modernism that survived to this day.

At the same time film production, art, culture, and theatre had created a zeitgeist of their own in Berlin. The city not only had a wide range of cultural offerings, but also a legendary, liberal, and sexually permissive nightlife. Weimar cabaret became known for its color, freedom, and decadence. The phase of the “golden twenties” ended in 1933, when the National Socialists came to power and Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the Reich.

Right after Hitler’s rise to the chancellor’s office life in Berlin started to change. The large Jewish population still living in Berlin became an immediate target. Around 1933 more than 160,000 Jews were living in the German capital. Some of them went into exile just in time, while many others were disenfranchised, deported, or murdered.

Within six years that population had been reduced in half. The SPD was banned in the summer of 1933 by the new Nazi government. Many of its members were jailed or sent to Nazi concentration camps. Fundamental rights were suspended, and trade unions and state governments were in effect powerless.

Terror reached a climax on the night of 9–10 November which became known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), when Fasanenstrasse Synagogue and Spandau Synagogue were burned to the ground and numerous Jewish shops destroyed and plundered. After 9 November 1938, the number of people of Jewish origin who made efforts to emigrate skyrocketed. In the few months before the war broke out, around 200,000 Jews left the Reich.

Hitler’s grand plans for Berlin as the “world capital” named Germany would be buried in the rumble of the allied bombings. By 1945 the whole capital lay in ruins. At the end of World War II, not only was Berlin destroyed, but it was also divided. The western part of the city was divided into an American, a British, and a French sector; the eastern part was under Russian administration.

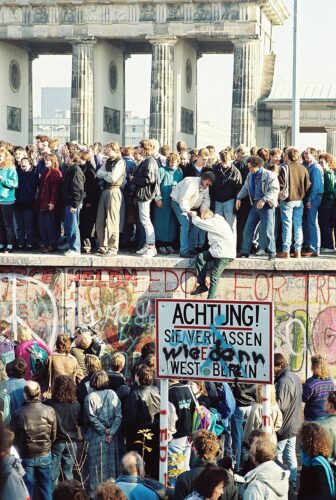

The city that was always destined to be in a state of flux, ever to change, was now an example of the division between the west and the communist regimes in the east. The Berlin Wall built in 1961 along the border of the Soviet sector sealed off the division. East Berlin would serve as the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) commonly known as East Germany.

The wall was in essence the Soviet dictatorship’s way to close the loophole of Easterners’ escape into the West. The wall became a worldwide symbol of the Cold War, which politically divided the world into an eastern and a western hemisphere. On the one hand, the wall was praised as a “peace border” and “anti-fascist protective wall”, on the other hand, it was condemned as a “communist wall of shame”.

It became a symbol of the bankruptcy of a dictatorship that was only able to secure its existence by imprisoning its people. The wall between East and West Berlin was 43.1 kilometers long. Well over 100,000 citizens of the GDR tried to flee via the inner-German border or the Berlin Wall between 1961 and 1988. Several hundred of them were shot by GDR border guards or died trying to escape.

In West Berlin, the population increased steadily after 1949 in the wake of the flow of refugees from the Soviet Zone, although a large proportion of the refugees was forwarded to the rest regions of West Germany. Within the decade up to 1958, the year of the Berlin Crisis, the population grew by 125,000 to 2.26 million.

After that, the number fell almost year after year. In the 1980s, the population rose again, reaching 2.13 million at the end of 1989. When the Soviet sector of Berlin was declared the capital of the GDR on October 7th, 1949, the population was around 1.2 million. In the period that followed up to 1961, the population of East Berlin decreased by around 150,000 people. This was primarily due to the strong movement of refugees, according to official information from the GDR, 22,000-30,000 people left East Berlin for the west every year. But the post-war death surplus also played a role, if only of secondary importance here.

On the other hand, the decline in the German population of West Berlin between 1960 and 1989 was only half offset by the increase in Berlin’s foreign residents. The recruitment of foreign workers – the main reason for the increase in the number of foreigners – began much later in Berlin than in the rest of Western Germany; In 1961 only 20,000 foreigners lived in the city. From the mid-1960s, the immigration of foreigners however expanded very rapidly.

In 1975 almost 190,000 foreigners were counted, and at the end of 1989 around 297,000. Among them, the Turks dominated, but also Poles, Yugoslavs, and also immigrants from the European Community, from the rest of Europe, and other continents formed the structure of foreigners. Overall, the proportion of foreigners up to 1989 in West Berlin was around 12%.

Between 1950 and 1989, not least as a result of the gutting of outdated residential areas, the number of German residents in the densely populated inner city districts – Tiergarten, Wedding, Kreuzberg, Charlottenburg, Schöneberg – decreased by 237,000. At the same time, it rose sharply in the peripheral districts (largely new housing estates) of Spandau, Tempelhof, Neukölln, and Reinickendorf.

In the inner city quarters, which despite considerable renovation efforts, had poorer building materials, largely foreigners moved. This is particularly noticeable in the Kreuzberg district, where the proportion of foreigners rose from 10% to 30%. In the east: the “workers’ palaces” of the GDR dominated the cityscape. Between 1950 and 1964, monumental apartment blocks were built along today’s Karl-Marx-Allee in the eastern sector of Berlin.

The buildings of the first, further east, construction phase were predominantly built in the style typical of the reign of Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union. In the west, the structural counterpoint to Karl Marx-Allee was the Hansaviertel in the northern Tiergarten. It was created in 1957 as a direct response to construction activity in the east and consists of several high-rise buildings and large apartment blocks in the modern style of the late 1950s.

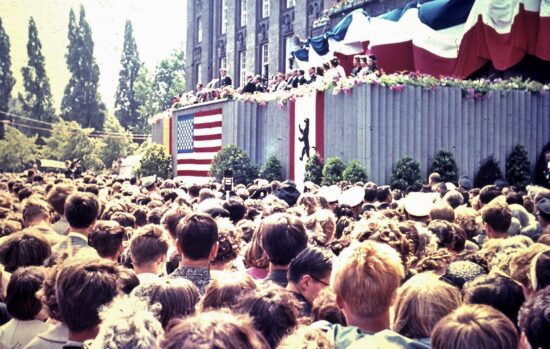

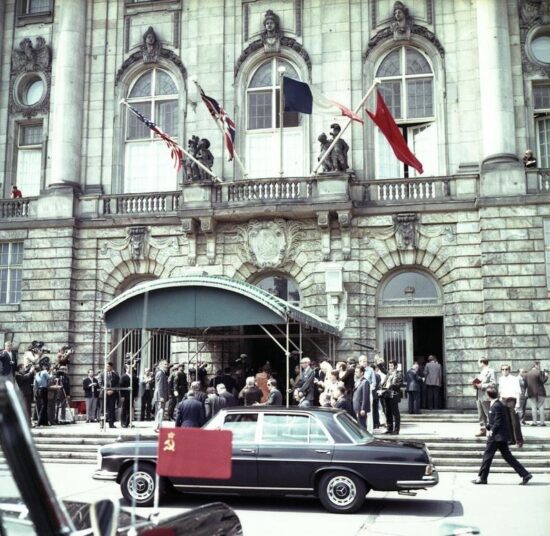

Kennedy’s famous speech Ich bin ein Berliner would mark the height of the Cold War in June 1963, in West Berlin. In the early 1970s in the course of a slow rapprochement between Eastern and Western Germany the former occupying powers the USA, Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France signed the four-power agreement. This regulated the status of the divided city of Berlin and introduced unhindered transit traffic from the Federal Republic to West Berlin.

The transit agreement meant a great deal of relief for German citizens who wanted to travel to West Berlin. A visit to East Berlin could now also be planned more quickly and easily for West Berliners. For goods, traffic by rail and on inland cargo ships, the agreement meant that civil goods could be transported unhindered in officially locked vehicles or containers. Although the transit agreement did not apply to traffic through the GDR to other Eastern countries such as Poland or Czechoslovakia, it resulted in numerous facilitations for passenger traffic.

Visas were issued directly and quickly at the border crossing points (GÜSt) of the GDR on the vehicle or the train, vehicles, and luggage should only be searched if there was justified suspicion of smuggling or foreign exchange offenses. The travelers no longer had to pay an extra fee but the rules were nonetheless strict. They were only allowed to be driven through for transit purposes.

On some country roads like the Bundesstraße 5, rule violations were much more difficult to control than on motorways. Ten years after the transit agreement came into force, the role of country roads as an undesirable meeting place and escape route ended with Autobahn 24 which connected Hamburg with West Berlin. historians rate the transit agreement of 1972 as a milestone on the way to German reunification.

The division between West and East Berlin had become unbearable for East Berliners who saw their neighboring countries of Hungary and Czechoslovakia loosen their border controls. As signs of the decline of the Soviet dictatorship became ever clearer over the spring and summer of 1989, the leaders of East Germany stubbornly adhered to distant, unrealistic slogans about victorious socialism. They chose to ignore the growing political opposition and demands for political reform and free elections. Peaceful demonstrators in East Berlin even dared to take to the streets during the regime’s official celebration of the 40th anniversary of the founding of the GDR on October 6 and 7, 1989. These demonstrations were immediately suppressed and more than a thousand people were arrested.

On the 9th of November of 1989 the spokesman for East Berlin’s Communist Party announced that starting at midnight that day, the citizens of the GDR were free to cross the country’s borders. East Berliners flocked to the wall, demanding the gates to open. Finally, astonished by the crowd East German guards opened the gates with no identity control.

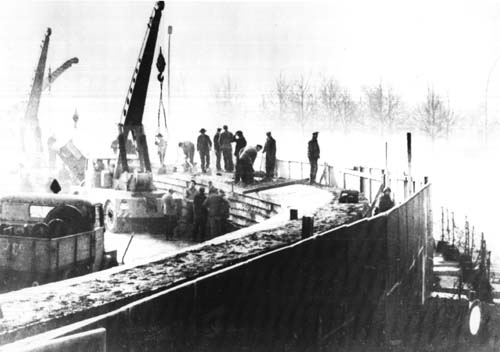

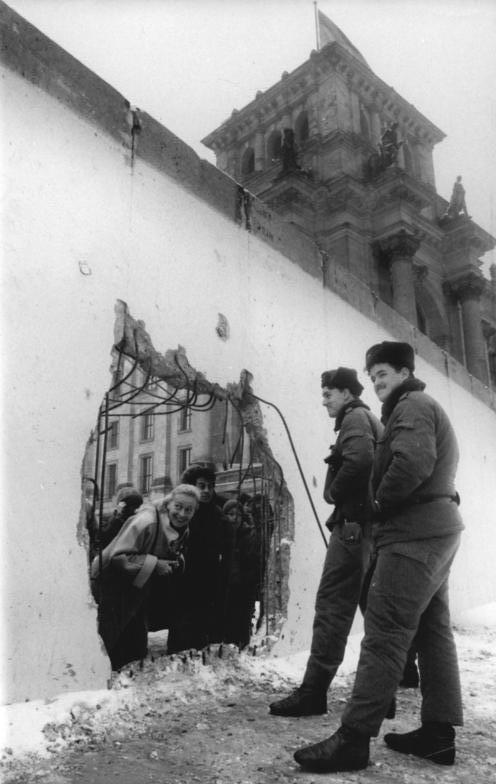

The doors had opened and would never close again. Crowds on both sides of the historic crossings waited for hours to cheer the bulldozers that would tear down parts of the Wall to reconnect the divided roads. In the beginning, the East German Border Troops tried to fix the damage done by the people who wanted a part of the wall as a souvenir of the new era known as the “wallpeckers”. After a few days, the guards would just turn the blind eye to the ongoing demolitions. By 1990 Gorbachev had signed the START I arms control treaty and had consented to German reunification.

“After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, West Berlin’s special status as an occupied city came to an end as the two halves were reunited to become the single city-state of Berlin. On 2 October 1990, the first joint Berlin legislature was elected. The traces of the city’s division were largely bulldozed under, most of the Wall demolished, streets re-joined and links between East and West re-established or created for the first time.

Thus, for example, the restored Oberbaumbrücke, a bridge that had once been a border crossing, was restored to traffic in 1995. In 2001, the city’s districts were realigned, with many of the new districts overlapping what had once been the Iron Curtain. Since then, the historic district of Mitte (meaning “Centre”) has once again become the true center of the city, home to many of its major attractions and museums. After unification, many districts, such as Prenzlauer Berg have been extensively refurbished and are now some of the popular residential areas in the city.” (VisitBerlin.de)